Dino Martins lectures to TBI students and Turkana beneath the shade of an Acacia tortilis.

|

Kenyan ecologist and Harvard PhD fellow Dino Martins began teaching ecology to TBI Field School students on Monday, placing emphasis on the ecology of the Rift Valley and the Turkana Lake Basin.

Rising global temperatures, induced by human hydrocarbon consumption and CO2 production, have already begun to exert an influence on east African ecology and human wellbeing. A major drought now extending into its third year is thought to be related in part to global warming, and has wiped out 80-90% of livestock in some regions of the Rift Valley.

Human patterns of land use also affect the health of local ecosystems, and Turkana in particular has suffered from overgrazing, and the harvesting of forests for charcoal. On Monday and Tuesday Dino led TBI students into the field, to begin a project that will help the local Turkana and global scientific communities better understand the ecological consequences of global warming, grazing, and forest harvesting.

Dino Martins stands beneath an Acacia as students begin their first field exercise.

Acacia tortilis trees are almost ubiquitous throughout Turkana, and are a critical component of the east African floral community. Grasses and sedges, though less visible, are actually of equal or even greater importance as primary producers: organisms that take sunlight and convert it into energy now available for animals higher on the food chain.

Mud and sand structures erected by termites in an Indigofera bush.

The species Indigofera spicata covers all areas protected from grazing by sheep and goats. It is a critical primary producer, harvested by many insects, and some species are used by humans to make deep blue dyes. Here, termites have built a complex series of sand tubes around an Indigofera bush which have protected them from sunlight as they harvested its leaves and wood.

Termites cannot digest wood directly, so in the example above the termites chew the wood and it is digested by bactera within their stomachs. Other termites in the region build large mounds, beneath which they tend to fungal masses, feeding them wood and then eating the fungi.

Veronica Waweru helps David, Priscilla and Chelsea with fieldwork.

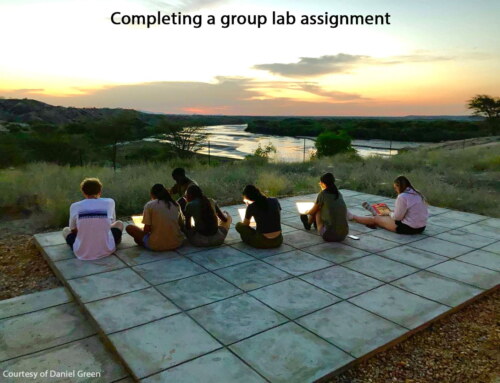

Students began their characterization of the flora of the area by running transects across which they carefully recorded species composition.

Dino with Patrick, Wyatt, Mandy and Meadow.

The burned stump of an Acacia beyond the confines of TBI.

Acacia trees survive scorching temperatures, low precipitation and periodic droughts by extending taproots into the earth, and accessing groundwater below. Some Acacia tortilis trees have been known to send down roots as deep as 300 to 400 meters. The trees in turn provide browsing mammals, insects, birds and even people with abundant leaves, bark, pods and flowers throughout the year.

People use tortilis pods for flour, and bark for medicine.

Companies in Lodwar and Nairobi have been encouraging locals to cut trees down and turn them into charcoal, buying charcoal from trees for about 2 USD per tree. The profits are immediate, but leave some areas destitute of foliage and inhospitable to people, their livestock and other animals. TBI Field School students travelled to areas where trees had been burned to begin assessing the impact of Acacia harvesting for charcoal.

Dino Martins lectures to students beneath the shade of an Acacia tortilis.

Students concluded their survey and sought shade beneath the spreading arms of an Acacia. A number of Turkana children joined them as Dino gave concluding remarks on the importance of careful, sustainable use of natural resources on both local and also global scales.