A rolled leaf left a fossilized imprint in volcanic mud at Kalodirr, West Lake Turkana, 18 million years ago.

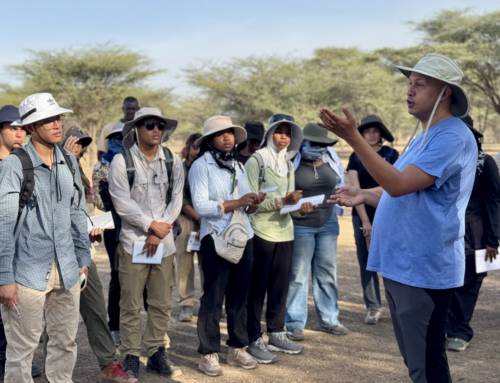

French paleoecologist Raymonde Bonnefille led TBI Field School students to Kalodirr last Friday, with hopes of finding fossil wood among the rocks. Heading farther north than on previous expeditions, Raymonde and TBI students had to hike over difficult terrain, impassable by their lorry. West of NW Kenya’s Lake Turkana, the region is among the most arid on earth and difficult to access even by Turkana pastoralists.

The hike was made worthwhile, however, by the discovery of a trove of fossil leaves and imprints, almost incongruous in the desolate landscape. These suggested that Kalodirr was very different, 18 million years ago, than it is today.

Raymonde Bonnefille is a French pollen expert, or palynologist, whose work has been dedicated to reconstructing the ancient environments of our ancestors in East Africa and elsewhere in the world. Though she continues her work in France at C.E.R.E.G.E., the “Centre Européen de Recherche et d’Enseignement des Géosciences de l’Environnement,” TBI students were fortunate to have Raymonde teach a Field School course on paleoenvironments of the Turkana Basin.

Pollen grains are produced by the millions and, under special conditions of sediment deposition, can be preserved in the geological or fossil record. Each species of plant has a unique pollen morphology identifiable under light microscope; when pollen grains are found in soil sediments they can be used to infer the species composition of ancient plant communities.

Fossilized woods and leaves can, similarly, be used to reconstruct ancient environments. Last Friday, on a tip from Richard Leakey, Raymonde Bonnefille and students headed out to Kalodirr, an 18 million year old Miocene site found north of the Turkwel River. The expedition proved more difficult than they had anticipated, but students found a stunning array of fossilized leaves.

Raymonde and students pass a series of shepherd trails en route to their site.

When the lorry could no longer cross the hilly landscape outside Kalodirr, students descended and trekked to their site, identified by GPS coordinates. As often happens in Turkana, mid day temperatures above the ground surpassed 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

Gastropod shells packed densely in a mudstone bed at Kalodirr.

Approaching the site, students recognized promising mud, sand and volcanic ash deposits eroding from hills slopes. The first fossilized remains they found were these gastropods, or snails, contained in a dense assemblage about 18 million years old.

Snails like these often remain buried in the mud until the rainy season, when they are awakened by floods and emerge to feed, and breed. Professor Craig Feibel told a story of one geologist who had collected a great many shells and assembled them into a lamp for his living room. One year, during particularly heavy rains, the snails he thought dead woke up, and his lamp crawled away in all directions.

A fossil leaf imprinted into a Lahar 18 million years old.

The fossilized leaves are found in a lahar, a mud and ash slurry that can move quickly across a landscape and bury anything in its wake. The mixture becomes especially mobile when even a small amount of water is mixed within it, and often entrains small particles, visible above, before it settles and solidifies.

A fossilized branch filled by quartz crystals and fine sandstone laminations.

The species to which this branch belonged is no longer identifiable, due to a remarkable process of transformation that has occurred in the millions of years since it grew on a living tree.

The inside of the branch was apparently hollowed, and later filled in a stream or riverbed with fine laminations of sand. These laminations recorded both the shape of the hollowed branch, and also some part of the history of the flowing water into which it fell. Around the sandstone, quartz crystals can be seen precipitating where one grew bark.

Luke Lomeiku examines a fossilized twig embedded within a lahar.

Some twigs and branches were better preserved, and finding one such specimen, Luke was careful to examine its woody structure until a field microscope.

A fossilized leaf imprint above mudstone at Kalodirr.

Raymond shows fossilized wood to Quan, Meadow, Wyat and Luke.

Professor Raymonde Bonnefille often makes use of these fossilized specimens in her laboratory to reconstruct ancient environments. Fossilized wood, like that above, can be prepared for analysis by cutting it into thin slices at precise angles, using diamond-tipped annular saws. The thin sections of wood are then polished, mounted on glass slides, and observed under transmitted light microscopes.

A number of different dicot species side by side at Kalodirr.

Leaf imprints left evidence of a number of different species once living at Kalodirr, but students were not able, at this time, to identify them. Professor Bonnefille was able to explain, however, that the presence of large leaves in this abundance, none now found in modern Turkana, suggest that the climate was once far wetter, or more mesic, than it is now.

The branching veins of an ancient dicot leaf preserved at Kalodirr.

Chelsea, Peter, Priscilla and Meadow gather around professor Raymonde Bonnefille as she shows them a particularly beautiful find.

A rolled leaf with intricately branching veins preserved in lahar at Kalodirr.

A series of small, delicately rolled leaves were found preserved within the lahar. Often, the leaves were rolling almost intact out of the stone.

A dense mat of twigs and monocotyledon leaves all fossilized at Kalodirr.

Students relax in the shade of an Acacia before hiking back to the lorry.

Before returning to the lorry and main camp, students hid for some time from the sun, under the shade of an Acacia. Students above include Meadow, Alisha, Ben, Patrick, Wyatt, and also Mandy, Peter and Chelsea.

An unknown tree species, with fruit, found in dry streambeds throughout Turkana.

We were not able to identify this species, which we have seen in a number of ephemeral stream beds, typically in very dry area. The trees reach heights of 5-7 meters, have no thorns and are heavily grazed by camels. Write if you have some clue as to the species!