Raymonde Bonnefille brought TBI Field School students to the local town of Lodwar, at the start of her course on paleoecology, to show them its local meteorological station. Lodwar is the largest town in northern Kenya, and its meteorological station has collected data benefiting the local airport and climate scientists worldwide for over 50 years. As professor Bonnefille would explain, an understanding of modern climate is invaluable when reconstructing the climate of the past.

Lodwar is the largest town in northern Kenya, and the administrative center of Turkana District, west of Lake Turkana. The town is surrounded by desert, so remote that in the 1950’s the British used it as a prison for Jomo Kenyatta, whom they accused of inciting the Mau Mau Rebellion. When colonial forces were expelled 10 years later, Kenyatta became the first president of an independent Kenya.

The same year that Kenyatta and five others stood trial while imprisoned in Lodwar, the city quietly began collecting meteorological data and has continued to do so ever since. While climate research did not immediately acquire the same publicity, this meteorological data subsequently proved invaluable to climate researchers in this and other regions around the globe.

Paleoclimatologists are interested in modern meteorological records because these can be used to reconstruct far more ancient climates. To help students understand how modern meteorological data are collected, professor Raymonde Bonnefille brought them to Lodwar and introduced them to local meteorological station staff.

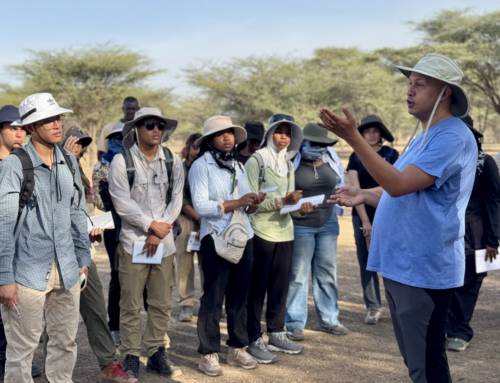

Professors Raymonde Bonnefille, Veronica Waweru and students listen as Mr. Manyoni gives a lecture on modern climate at Lodwar.

TBI Field School students were introduced to Mr. Manyoni, a meteorologist whose work is used by local pilots, researchers and climatologists.

Mr. Manyoni describes the way in which his data is transmitted to Nairobi and made accessible to climate researchers globally.

At the Lodwar station, meterology staff record precipitation, humidity, temperature, windspeed, evaporation and pressure either every hour or every three hours. Their work requires shifts that cover all 24 hours of the day.

The meteorological station in Lodwar uses a Campell-Stokes tropical sun recorder.

This device was invented over 150 years ago, but is still in use all over the world. The light of the sun is directed through the glass sphere to a point, where during daylight hours it burns a hole through a small paper card. By tracing the burn marks on a card a researcher can record the hours and strength of daylight.

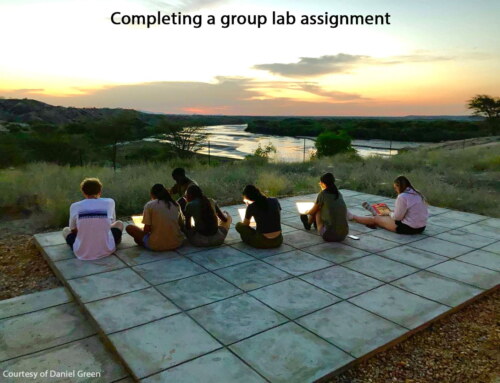

Patrick and other students look out over the Pliocene sediments at TBI main camp during a morning class with Raymonde Bonnefille.

Following their trip to Lodwar, Professor Bonnefille brought students into the Pliocene sand, sandstone and mudstone sediments outside TBI’s main camp to look for deposits that might contain pollen. Above, students sketched a quick geological map of the area before they began to explore.

Professor Bonnefille explains the significance of a mudstone deposit in the Kataboi member of the Nachukui formation outside camp.

These sediments, approximately 3.5 million years old, consist of mud deposits created by a flood plain of the ancient Turkwel River. While riverbeds are full of fast flowing and turbulent waters that wash away fine grained muds, floodplains are calmer and tend to preserve fine sediments. For this reason, professor Bonnefille explained, they were more likely to contain microsopic pollen grains.

Professor Bonnefille points out a sandstone column in the ancient sediments outside camp.

Students enjoy the view over the Pliocene sediments outside the Turkana Basin Institute’s Turkwel River camp.

Before students returned to camp for lunch, professor Bonnefille managed to locate a number of mud sediments altered by volcanic ash. Excited by the find, students explored all over the deposite and found many fossils in the process. Volcanic ash can be used to date sediments, giving a concrete ago to ancient material preserved within them. For palynologists, ash is exciting because it preserves pollen: the fine interface between an ash layer and the sediments below it is often full of ancient pollen grains.