The road to ecological disaster is paved with good intentions. Years ago, an aid organization introduced Prosopis to Kenya. The relative of the acacia seemed like the perfect plant to rejuvenate the arid regions of Kenya. It grew quickly in intense heat, thrived in arid soil, renewed forage on rangeland and provided wood for charcoal production. Again, good intentions.

Prosopsis crowds the edge of the river in the center background. The cattails on the left and right were once the dominant plants along the water’s edge on the Kerio Delta.

The Prosopis took to Kenya with too much enthusiasm and is now choking out the floral diversity ringing the deltas that feed Lake Turkana. The Prosopis crowd the shoreline and fill every available open patch with spiked fronds. The decreased plant diversity means fewer places for fish to spawn and mature and the salt-intolerant Prosopis act as a carbon sink as the salt-intolerant plants drop into the water. The Turkana can’t chop it down fast enough as it consumes the landscape. Sounds like the perfect place to spend a Saturday.

A close-up of the invasive South American plant that is rapidly taking over the freshwater ecosystem.

Dr. Dino Martins led a field excursion to the Kerio River delta to examine the effect the Prosopis is having on the local ecology. As the truck full of students bumped along the dirt track towards the lake, the plain was suddenly filled with spikey Prosopis. We walked through the thickets and looked for pollinating insects and other plants making a push for space, but the best way to examine the effects of the invasive plant is from the water.

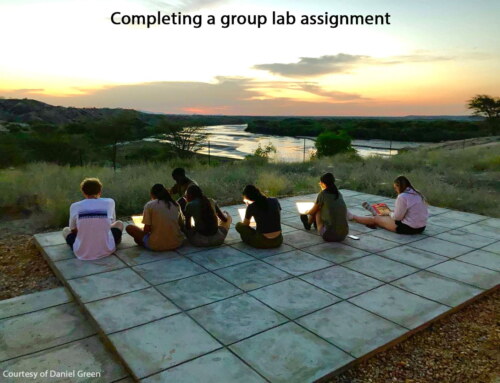

Francis and Dr. Martins arranged for a couple of Turkana fishermen to take the class out in small groups to survey the river as it feeds Lake Turkana, the world’s largest desert lake.

As the Turkana fishermen paddled us along the Kerio River, we watched the shoreline for insects and birds making a living off the drastically altered river margin environment. Pied kingfishers swooped low over the water on the hunt along with beecatchers, malachite kingfishers, little green herons, and a solitary Goliath heron, the largest of the fishing birds to cruise the shoreline.

Near the river’s mouth, the Prosopis reluctantly gave way to cattails and the open water of Lake Turkana. On the horizon loomed Lothagam, a large outcrop of Late Miocene rock that we will be visiting in a few weeks. Up the narrow channel of the river we could also make out the cratered profile of Central Island, the biologist’s paradise we will be exploring next Sunday.

The Late Miocene site of Lothagam looms over Lake Turkana, a geological temptation we will explore in a few short weeks.

The original plan had been to turn the boat around once we reached the lake, but the fishermen wanted to examine their nets, which only seemed fair since they had hauled our constantly swiveling bodies down river. A white buoy marked the end of the first net suspended near the water’s surface, snaring large fish that tried to dart through the warm, mildly salty waters the net transected.

Each caught fish needed to be untangled from the net. These trapped fish make temptng bait for the crocs that also call Lake Turkana home.

As we creeped along the net, the students had the chance to meet some of the freshwater fish that call Turkana home. Nile perch and Nile tilapia are staples of the fisherman’s haul and they were in abundance, their name demonstrating the geologically recent connection Turkana shared with the Nile River. More exotic fish included catfish with long whiskers and trailing tail streamers and a tiger fish, an animal named for the massive, caniniform teeth crowding its mouth.

A fanged tiger fish demonstrates how it earned its name. The fish will mostly be consumed by the fishermens' families, but some will be dried or smoked and sent to market.

Soon, the floor of the boat was filled with fish, though the fisherman did not plow through the lake, taking every fish in their path. Instead, they managed the lake’s resources, throwing female fish back into the lake and allowing smaller fish to swim through the net unscathed.

The return journey took the boats past hippo trails through the reeds and back to the Prosopis-dominated wetland. In an environment as arid as the Turkana Basin, sustainable management of freshwater resources is critical, and such management relies on careful collection of raw data on the plants and animals that call the rivers, deltas, and lake home.

Several of the students in the field school have taken on research projects that address the freshwater ecosystem in such an arid setting. Aaron and Rachel are examining insect communities along the Turkwel River while Rosie considers the river’s fish diversity and the parasites that live on the minnows and tilapia in the river and in the newly-built fish ponds at TBI, the brainchild of Acacia Leakey.

Sam and Rosie collect samples for their independent research projects on the ecology of the river and partitioned fish ponds.

Ashley is looking into the invertebrate, microfaunas found in each of the new fish ponds and in the open river. Sam is going to the root of the Turkana freshwater ecosystem by studying the diversity of algae found in the separate fish ponds while Holly and Meg are looking at the abundance and diet of water crickets along the river.

Ideally these student projects generate hypotheses and pilot data that will seed further research on the delicate freshwater ecosystem in the Turkana Basin as it struggles to find balance in the face of climate change, invasive species, and human population growth.