At first glance, the Turkana Basin can seem like a desolate place with a pretty simple food web. Looking out over the landscape, there are widely spaced acacias across the sand flats with scrubby, needle-bearing Indigofera shrubs filling in the gaps for hungry herbivores.

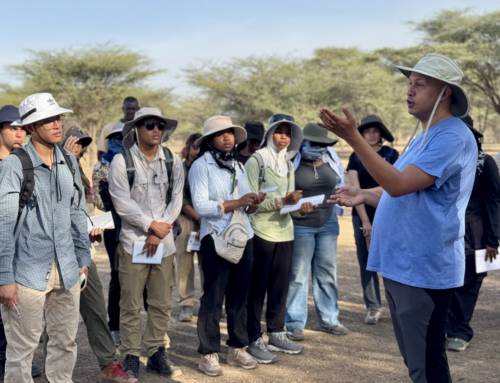

But when you look a little closer, there is a hive of activity on a much smaller scale as pollinating, burrowing, and carnivorous insects jostle for space among the flowers, seeds, and leaves. The pollinators are the special interest of Dr. Dino Martins, and he led the students on their inaugural entomological excursion to a temporarily lush field where bees, flies, and grasshoppers were in the insect equivalent of paradise…if paradise includes intense predation pressures and a scramble to exploit the verdant pasture.

It was actually shocking to see so much green blanketing a space surrounded by the familiar sandy backdrop. Dr. Martins handed out nets and offered a few tips for catching the insects buzzing around the small yellow flowers and abundant love grass.

The desert was suddenly interrupted by a lush plain of ready pasture that supported grazers both large and miniscule.

“You have to sweep your net over the collection area with some energy. Don’t be afraid to look a bit mad.” Sure enough, after a few sweeps, he had collected several bee specimens that were pollinating an unfamiliar flower.

The students then spread out over the pasture and tried pouncing on the equally energetic grasshoppers, flies, and spiders. After a few empty swipes, Meg appraised her partner’s technique, offering, “I don’t think you look crazy enough.” With a little more crazy, there was a grasshopper bouncing around in the net.

Cory and Leanna try to add a little madness to their butterfly netting. They actually managed to haul in a few more insects with their vigorous method.

After a bout of collecting and getting an idea for the hidden insect diversity of the desert, the students again spread out to collect abundance data on the grasshoppers by walking transects and counting the number of herbivorous hoppers along the route. Such data is difficult for an entomologist to collect with such rapidity under normal circumstances, but the field school offers many willing and able research assistants for these on-going ecological projects.

A red-veined dropwing briefly rests before moving on to catch its next meal on the wing.Tim holds up a melon-like fruit growing in a patch of dense herbaceous plants. Not many animals can stand the bitter pulp, and Tim wanted a look inside this fallback food.

Walking back towards the vehicle, the class walked past the larger herbivores exploiting the lush field. Herds of donkeys, cattle, and camels moved across the landscape. Their attending herdsmen came to make sure their stock was left unharassed by the students who kept their respectful distance while admiring the juveniles in the herd.

After a morning of insect-gathering, the students spent the day working on their individual ecological research projects. At the end of the week, each student in the field school will present original research on either Turkana plants, insects (particularly disease vectors), or the Turkwel river ecosystem.

The students working on the vegetation are focusing on the differences between the heavily grazed landscape outside the TBI compound and the ungrazed plants within the compound. Cory spent some time talking to Francis, a Turkana researcher and field assistant at TBI, about how the Turkana manage their livestock while Eve and John observed the habits of the roaming camels and goats foraging among the shrubs and trees. Francis, a researcher from the Kenyan National Museums, collected transect data outside the compound to consider small plant diversity on the grazed plain while Marcel walked long transects to account for tree species diversity and size.

Cory and Eve learn the names of the students walking home from school. It's hard to work on the Turkana ecosystem without drawing some attention and meeting a few new friends.

Other student research topics will be featured over the next couple of days. Suffice it to say, everyone has become familiar with the complexity of ecological research and the interdisciplinary nature of every question researchers could pose in the Turkana Basin. It’s not a barren, simple ecosystem at all, but a complex environment where plants, animals, topography, water, and people interact on every imaginable scale.