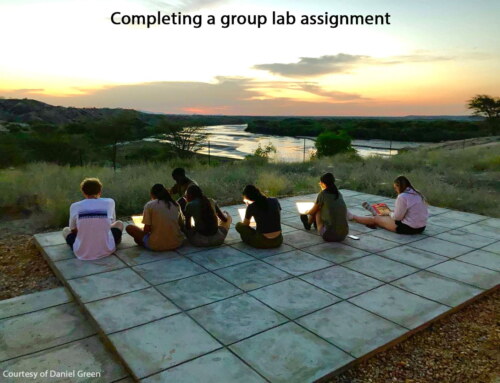

After two days on the road, everyone was still game to get to know one another before hiking down to the lake.

For paleontologists and archaeologists it can take a lot of imagination to conjure up the ancient environments that surrounded the animals and artifacts being excavated. Without a clear idea of the environmental context that surrounded the material exhumed from the ground, it’s tough to examine the clues to paleoecological interactions preserved beneath our feet.

The Turkana Basin today is a relatively arid scrubland but data discovered in the isotopic, floral, and paleontological record indicate the landscape was once lush, with crocodiles and hippos in the rivers and lakes, and giraffes and rhinos browsing the foliage.

So, the Spring 2013 Turkana Basin Field School began course work with ecologist Dr. Dino Martins, not in the badlands of northern Kenya, but in the verdant Central Rift Valley along the shores of Lake Elementiata and Lake Nakuru.

Still slightly jet-lagged and tired from a trip over the Atlantic, Europe, the Mediterranean, and Saharan Africa, the students pushed on to Pelican Lodge on the shores of Lake Elementiata where flamingoes skimmed for food on the water’s edge along with spoon billed storks, pelicans, dippers, and sacred ibises.

Dr. Martins lead the walk along the water’s edge, pointing out the birds soaring overhead or splashing into the inland, salty lake, noting the specific adaptations each animal possessed for chasing down its preferred next meal.

The first group-shot of the Spring 2013 TBI Field School. Many more to come. They probably won't be as spread out as they get to know one another...

After a well-earned rest in beautiful cottages along the lake, we woke up early to get to Nakuru National Park to observe East African Megafauna in all their ecologically complicated glory. As the bus rolled through the park, the students studied each new animal in its natural environment and Dr. Martins pointed out the several roles each species serves in the diverse ecosystem that makes Kenya such a fascinating place to be a naturalist.

We observed ungulates with different social structures such as the impala (Aepyceros melampus) with large herds of females rallying around a single male, and the bachelor herds waiting in the wings to move in. We also witnessed several white rhino (Ceratotherium simum) basking in the sun. These critically endangered animals sport a wide, squared mouth perfect for acting like a massive, grass-munching vacuum. We even had the rare opportunity to see a mother and her calf foraging along Lake Nakuru.

In the middle of the day we stopped for a stretch break and watched a troop of olive baboons (Papio anubis) approach the campsite we had stopped at. The two groups of primates watched each other, the humans observing dominance displays, romping juveniles, and the constant, precise plucking of forage as the baboons glanced back, witnessing excited student discussion of social structures in other primate groups and the baboons’ adaptations to the grassland environment.

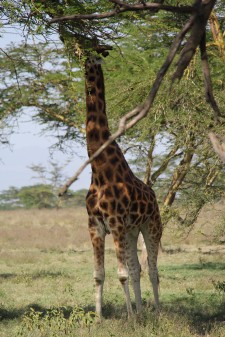

After over an hour of fascinated observation, the Field School climbed back onto the bus to watch endangered Rothschild’s giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis rothschildi) moving beneath the acacia trees. Despite their towering stature, the animals blended into the mottled shadows, but some foraged close enough to the bus to let us count the five horns that erupt from the Rothschild’s giraffe’s head.

The white "stockings" and five horns of the Rothschild's giraffe sets this subspecies apart from other, more common giraffes in East Africa.

Our final stop took us to the top of a cliff overlooking Lake Nakuru. Far below, a hippo swam beneath the water near a small flock of flamingos. Closer to the students, a group of rock hyraxes (Procavia capensis) leaped along the edge of the cliff, wrestling, hunkering down on the rocks, and grazing. The students learned hyraxes, which look something like short-eared, grumpy rabbits, or large, still-grumpy guinea pigs, are actually closely related to manatees and elephants, a massive heritage suggested by their pointed incisor “tusks” and short, hoof-like toes.

The extinct relatives of modern hyraxes filled the horse and rhino niches of ancient Africa before many ungulate taxa such as true rhinos, horses, and bovids invaded the continent when Africa docked with Eurasia about 20 million years ago. Students were then able to share their new insights on these strange, little mammals with other visitors to the park who had never heard of the small mammals.

Soon, we were joined on the overlook by another troop of baboons, this group more accustomed to people and much more interested in foraging for half-finished lunches.

Rosie also had a moment to spend in quiet contempation with a curious olive baboon near Lake Nakuru.

After a final cruise along the water’s edge and an opportunity to watch a zebra foal stumble into its mother, cape buffalo calves hemmed in by the herd, and young vervet monkeys watching the bus curiously, it was time to leave the park with the setting sun and get a good night’s sleep at the Flamingo Lodge before catching a plane in the morning for Lodwar and the Turkana Basin Institute.

After a year of unusually abundant rain, this hippo was able to swim among acacias that once stood on the shores of Lake Nakuru.

Now it’s time to learn about the ecological setting of the modern basin with Dr. Martins. Then, we’ll be diving into the geological past where the extinct ancestors of the creatures observed from our bus populated the landscape alongside our own extinct relatives. On to Turkana!