Just upriver from the Turkana Basin Institute, a revolution is taking place.

On a small plot of land along the riverbank a women’s collective is trying to cultivate crops. There are a couple of factors working against them. First and foremost, the Turkana are not farmers. They are herders, and much of their traditional subsistence knowledge centers on caring for livestock, not sowing seeds. Second, the sandy soil of Turkana doesn’t exactly scream amber waves of grain. And finally, as women, their position in the social hierarchy as farmers is still being navigated in the patriarchal Turkana culture .

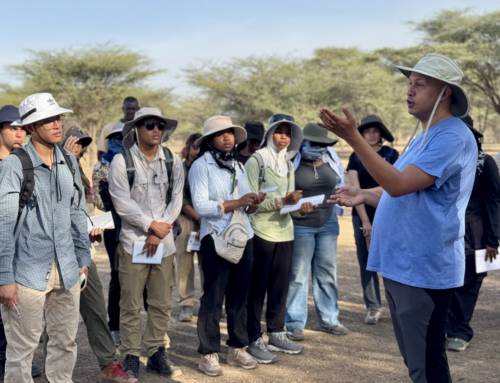

Despite these issues confronting their efforts, and many more, the women’s collective has (so far) successfully transitioned about thirty women to the sedentary farmer’s lifestyle. We had the opportunity to visit their two acres of cultivated earth to witness the revolution in action.

A young boy works the irrigation pump, providing water to a variety of crops including peas, corn, and peppers.

In order to cultivate their knowledge of crops the women and their children have been adaptable, learning what works as they try to divide the labor among thirty partial owners. At first, each plot contained a single crop, but they’ve decided to diversify each section, making a smaller group of people responsible for a wider variety of plants. Half of everything earned by selling the produce is deposited into a joint account and the other half is evenly divided among the collective’s members. TBI is one regular customer they work with and from personal experience, I can tell you the fruits of their labor are delicious.

A Turkana women demonstrates how to access the Sweet-Tart-like rind of the doum palm. She expertly pounded the surface, flaking off sweet shrapnel to share with her guests.

A key tool in turning the sandy bank to flowering fields is a simple, foot operated water pump. Nicknamed “the moneymaker” by many Kenyan small-scale farmers, the purchase of the inexpensive, rugged pump was subsidized by TBI. Water is drawn from the nearby river and pumped through movable irrigation hoses. Using the device is akin to sweating on a stairmaster and is surprisingly effective at moving large quantities of water without much effort.

Natalie tries her hand (or foot) at drawing water from the nearby Turkwel River to the growing garden plots.

The water trickles through the plots, causing a variety of crops including cowpeas, corn, peppers, and papaya to grow in abundance. Of course, where there are green plants there are insects. One concern some environmentalists raise as agriculture spreads across a biodiverse regions is the possible reduction in insect diversity. Many plants have an evolutionarily selected suite of pollinators and seed dispersal agents, and the fewer plans on the landscape (i.e. a field of corn rather than a diverse forest) the fewer insect species are necessary to make the system work. Testing this observation, the students spread across the gardens and studied the insects associated with each crop and found an incredible diversity of animal life associated with the domesticated plants.

The source of the water that fuels the flourishing gardens is close at hand in the Turkwel River (on the left). The Turkwel River is dammed upstream, but is allowed to have a constant flow of water throughout the year. Before the dam, this was a seasonal river and agricultural experiments would have been a lot harder to pull off.

There were a lot of opportunities to take photos of thoughtful students such as Rosie and Eve as they tried to classify the insects they observed on the crops using their own insights and experience.

The insects were observed and evaluated for their positive or negative affects on the plants. Some insects, such as the blister beetle, so named for the irritating reaction people have to a compound it secretes, were munching away on cowpea flowers. Clearly this animal is a menace to the novice farmers along with the weevils that manage to destroy half the ears of corn still on the stalk. However, a greater proportion of insect life was deemed beneficial, either hunting the very hungry beetles and weevils or pollinating the plants in the plots.

Is this beetle good or bad? If pesticides are brought into the garden, how many necessary insects will be lost with the pests? Such is the stressful calculus of farming.

The students also took account of crop yields, creating a database of agricultural data for the collective and TBI, one of the many customers interested in buying (and consuming) the garden’s produce.

As we observed the day before, the Turkana lifestyle is rapidly changing. People aren’t able to move as freely across the range as they once did, tied to specific places and distances by educational resources, healthcare, and food aid. As they become sedentary, perhaps cultivation agriculture will become one resource for diversifying their wealth and food resources. The early experiment seems to be a success. It’s amazing what a little investment can yield…and a lot of time on the pump.