Lothagam isn’t a name that comes up very often in Physical Anthropology classes. It wasn’t a name a lot of the students on the field school knew before they came out to TBI. But over the last few weeks there was a building drumbeat: Lothagam: the lonely hill on a distant horizon. Lothagam: the oldest window into the Cenozoic in the Basin. Lothagam: the home of abundant fossils. Lothagam, Lothagam, Lothagam!

Lothagam! Lothagam! Lothagam! To the left (East) is the edge of "The Horst" while the fossiliferous rocks dip off to the right (West).

By the time we loaded up the truck with Dr. Craig Feibel in the cab, bedrolls stashed in the back, and students crammed any way they would fit, we were stoked to see the wonders of Lothagam for ourselves. The red rocks did not disappoint.

Packed and squished but stoked to finally see what all the fuss is about (Left: Ingrid, Rosie, Eve, Sam, John, Ashley, and Tim...oh, and gear)

We rolled across the flat desert, broken by the occasional Prosopis, Acacia, camel, and bustard (a giant, near-flightless bird) towards the only slice of interesting topography to the south. We had been prepared for the excursion by a series of lectures on the evolution of the Turkana Basin and the geological importance of Lothagam. As the outcrop’s profile came into sharper focus, we could discern the tectonic forces of nature that had preserved this rare glimpse into evolving Africa.

At some point in the last 3 million years, a massive block of volcanic rock was launched skyward, forming a “horst” or uplifted chunk of rock. It dragged the seven to 3 million-year-old sediment attached to its flanks along for the ride. The crucial time period recoded in this raised block of stone includes the transition from a forested environment to the grassland environment that now characterizes the African continent.

The Horst acts as a bulwark against the marching desert sand. Field School students in lower left for scale.

It’s difficult to imagine Africa without swaying yellow grasses on the ground and elephants and zebra chomping through, but six million years ago the savannah was a brand new landscape, and the animals were actively adapting the open conditions that would later be slapped across postcards and the pages of National Geographic.

When we arrived, we set up camp in a wide riverbed in the soft sand that occasionally hosts seasonal flowing water, but otherwise provides a lovely place to spend the night. The larger truck was parked on one side of the riverbed, and the smaller Land Rover parked forty feet away. Rope was strung between the vehicles for suspending mosquito nets and sheltering bedrolls.

It was time for the first hike of the day, an excursion to the east side of Lothagam where the desert smashes up against the horst. The winds roll across the flat expanse of desert and wash against the monolithic basalt. Like waves on the ocean, the wind drops its load of sand and builds the dunes that march towards the outcrop. We explored the sliced dunes and sheltered under persistent palm in our walk to the foot of the horst.

Dr. Craig Fiebel leads the Field School to the best shaded spots for the outcrop talk on the spectacular basalt flows suspended over the desert.

The rocky face was scarred with the effort of rising above the desert with deep gauges and altered minerals indicating the titanic forces that dragged the rock out of the ground at a 45 degree angle. Dr. Feibel taught the students their final key geological skill when he brought out the Bruntons and taught them how to document the strike and dip of the fault, the trend of the rock and it’s tilting angle. Now they’re ready to meet a new outcrop and transfer what they see to paper for other geologists to interpret.

Field Crew at fault. They except the blame. (Left back: Francis, Marcel, John, Francis, Maegan, Sam, Meg, Leanna, Rob, Ashley, Rachel, Aaron, Dr. Feibel. Left front: Bailey, Holly, Eve, Cory)

On our way back across the desert, we watched the tracks of desert creatures that had wandered across the sand, including lizards dragging their tails, small birds, scurrying scorpions, and a large porcupine who etched the sand with his iconic quills.

Bailey, Natalie, and Rosie try their hands (or heads) at porcupine quill sparing. Fortunately there was eye protection involved.

As the morning wore on, the temperature rose, but before beleaguered bodies could give in to the heat, a beautiful triple corona rainbow rippled around the sun. Suddenly energy surged back into limbs and myriad photographs were taken from the outcrop with the rainbows, dust devils and the stark joy of the desert gearing us all up for our afternoon hike into the badlands.

Protected from the strongest erosive blasts of the desert, the uplifted sediments tilt off to the west, leaving the layers of rock documenting East Africa’s grassland revolution exposed to paleontological curiosity. Dr. Meave Leakey and Dr. Craig Feibel have spent many field seasons unraveling the stories preserved in the iron-stained sediment.

Dr. Feibel led us through the maze of canyons and outcrop, pointing out the signs of flowing water in the rock deposits. But my favorite indicators of freshwater were the fossils. Literally tons of fossils. The ground was littered with the teeth of hippos, the ankles of giraffes, and the jaws of crocs. For many of the students, this was the first locality they’d ever visited where they could pick up fossil bone. It was tough to keep the focus on the rocks when the fossils were tumbling out around our feet. The outcrop itself was riddled with caves and gullies offering some challenging scrambles through the geological record.

Near a winding gully, Dr. Feibel stopped and skewered the rock with his machete. “We are crossing the boundary. Here’s the transition from the Miocene to the Pliocene.” Boundaries are a big deal in geology. Different units of geological time are identified by the biological changes recorded at the transition. Here we crossed from the relatively lush to the drying African landscape. Elsewhere on the planet, the Mediterranean Sea dried up completely and the entirety of Southern Europe and Northern Africa became a forbidding salt desert

It was worth posing for a picture.

Climbing from the badlands, onto the foothills of a second boundary basalt that stood out against the western horizon, we were suddenly standing in the Holocene, our current geological home. Evidence of the expansive Lake Turkana we’d seen at other localities was again under our feet with beach sand and well-rounded stones. These stones were noticed several thousand years ago by people who apparently thought Lothagam was a pretty special place, too and buried their dead along ancient Turkana’s shore. Pottery fragments and chipped stone sat among the rocks and rings of stone that marked the final resting place of the several ancient Turkanans. One burial included an arrangement of small pillars of basalt.

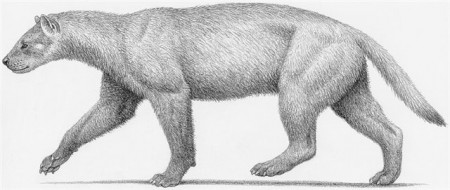

After spending some time with the relatively recent past, it was time to dive back a couple million years to the Miocene and visit one of the more complete residents of ancient Lothagam: Ekorus ekakeran. The name means “Running Badger” in Turkana. The lanky relative of otters and weasels stood over half a meter at the shoulder and would have had a wicked, wolverine-like bite. Some analyses indicate it was an ancestor to the honey badger, one of the more ferocious little mammals in Africa today. A honey badger the size of a hyaena would be terrifying animal to encounter. Sometimes extinction doesn’t seem like such a bad thing.

A high stepping Ekuros ekakeran as reconstructed by Mauricio Anton based on the material found at Lothagam.

The fossil was recovered in its entirety by legendary Kenyan fossil hunter Kimoya Kimeu through careful excavation of the skeleton under a shelf of overhanging rock. The animal was curled up in a fossilized soil horizon, suggesting it was buried in its burrow. Today you can share it’s burrow by curling up in “Kimoya’s Cave.”

Francis, our Turkana translator, experienced prospector, and patient guide, had a couple options for taking a load off at the end of the day. The stool to the left is a traditional spot for a Turkana to take a breather.

The first day of the Lothagam excursion finished, it was time to crawl the rocks searching for horse teeth and elusive human relatives. Then a well-earned dinner and a spectacular sunset over the western rim of Lothagam. The stars were out in force, clearly visible through mosquito netting. The astounding view of the night sky didn’t last long as I drifted off to well-earned sleep on a thick mattress in the soft sand. The most luxurious night I’ve ever spent sleeping on the ground, an important asset when there’s only one more day to explore Lothagam.