Geology is the foundation science. Pun intended.

It is the study of how everything we can lay hands on came to be. Geology draws from every investigative discipline – physics, chemistry, biology, anthropology and a lot more ologies – to examine the wheres, whens, and whys of mountains, water, and us.

But before a geologist can start to answer questions like “How did the planet form?” and “Where did bipedal apes come from?” she must equip herself with a few basic skills that will make gathering data and weighing hypotheses a little easier.

Without a few basic skills, this badland landscape makes for some nice Ansel Adams-esque photography, but reveals precious little about the geological history of the Turkana Basin.

At the Turkana Basin Institute we are fortunate to have Dr. Craig Feibel, professor of geology at Rutgers University, to guide us through the basics…and the advanced. He’s been working in the Turkana Basin for over thirty years and knows many of the stories these sediments have to tell and he’s always reading the rocks for a few more.

Dr. Craig Feibel explains the history of the Turkana Basin which begins with the Great Rift, involves a massive, wandering river system, and ends with the largest desert lake on the planet. He has a few tools ready to go on his utility belt and will teach the field school students to add a few to their own kits.

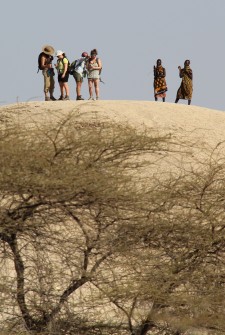

Just west of the institute are small, steep buttes and gullies that form a dramatic backdrop to the camp’s mess hall and a great place to do a little hiking in the early evening. Dr. Feibel led us in to teach us to read the rocks, too, rather than simply admire their stark beauty.

A typical butte south of West of camp. The rock is pretty much the same sand all the way through. The better cemented material that forms the caps are a secondary effect from running groundwater.

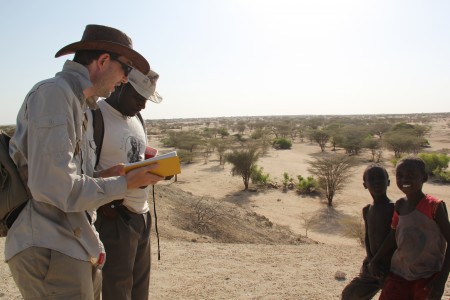

The geology walk is a basic feature of any geology field course that tests the student’s ability to write in a notebook while standing in the wind and sun with sunscreen smearing the ink on the page and a determined fly strafing his earlobes. It’s a honed craft and we will have plenty of outcrop opportunities.

Dr. Feibel shows the field school students how to recognize evidence of roots breaking through the rock and the bedding structures locked in the sand that reveal the former activity of the extinct river. (Left to right: Dr. Feibel, Ana, Rachel, Tim, Aaron, Cory, Sam, Maegan, Ingrid, Marcel, Meg, John, Bailey, Leanna, and Holly)

Dr. Feibel showed us how to see the Pliocene river that flowed through the area 4 million years ago, depositing coarse sand, gravel, and fossils. After the river changed course, ground water percolated through the loose sands and hit layers of clay that forced the dissolved calcite out of solution and between the sand grains, cementing some layers in place. Today, these secondarily cemented layers form beautiful disks and swirls of hard sandstone. The more erosion-resistant layers compose the tabletop surfaces of the buttes that surrounded us. He then pointed out fins of rock and pulverized minerals in the walls next to us, evidence of faulting and expansion: the Great Rift on a local scale.

A group of Turkana women balancing water watch us scramble over the rocks. On the right is a fault locked in stone. The fin of rock was formed when a block of material dropped, leaving a crack that was filled in with sand and water, forming a natural cement. Now the material that dropped in the first place as eroded away, leaving mohawks of stone as evidence of East Africa's tortured geological history.

Pointing out a pile of crocodile skull fragments, he helped us lock into the fossils found in the rock. Suddenly our Pliocene river was populated by Euthecodon and five other species of croc. Compare that to the single species, the Nile crocodile, found in today’s Lake Turkana and this Pliocene river seems like a rough place to go for an evening swim.

For some of the students, the croc bones on the ground were the first vertebrate fossils they'd ever encountered in the field. Maybe not the prettiest set of bones, but a momentous occasion. (Left to right: Marcel, Dr. Feibel, John, Leanna, Bailey, and Holly)

Leading us upslope, Dr. Feibel pointed to a pile of thin bones marked by a cairn. “Any ideas on what this is?” Those who have taken human osteology tentatively answered, “Skull fragments?” Yup. Human remains. Not four million years old, though. These are fully modern human remains from a culture that preceded the Turkana people and buried their dead along the ancient Turkwel under small mounds of Pliocene sand.

Bailey and Eve examine modern human remains from burial sites that were dug before the Turkana arrived in in the basin named for them.

The next day we hauled out the compasses and measuring tape. Each student learned the length of their pace and how to use a Brunton survey compass. With a better sense of North and how to measure the distance from the classroom to the mess, the students broke into groups and drew maps of the compound. A task that defines easier said than done.

Bailey, John, and Holly pace out the distances between the buildings and the calculate the orientation of Abby Road (maybe Abby Sand Trail).

Camp is pretty straightforward. A series of square and rectangular buildings set at slight angles to one another. But finding the dimensions of each structure, the offset of each veranda, and the distances from structure to structure required patience with the compass, even paces, and careful note-taking. Map-making is the bread and butter of geology, the way a geologist starts to piece together the relationships between the rocks and the fossils or artifacts found within. As the newly christened geologists learned, map-making is also the source of frustration and a lot of sweat.

Natalie wasn't phased by the compass and pacing exercise. A good person to have around in case you plan on getting lost in the desert.

But everyone muscled through. Rocks. Check. Compasses. Check. Pacing. Check.

Now to travel to the third dimension and figure out how to calculate height. Along with the compass, field notebook, and maybe a hammer (or in Craig’s case a machete) geologists keep a Jacob’s staff in the tool kit. The striped stick serves to measure regular intervals marked by carefully drawn stripes along the pole. They’re also convenient walking sticks for rough outcrop.

John holds a 1.6 meter Jacob's staff after Bailey has taken her measurement. Using a Jacob's staff means measuring elevation which means there's a lot of uphill scrambling as Bailey is demonstrating.

By using the compass as a level and sighting to a precise spot on a hill the aspiring geologists and mapmaker can calculate height at regular intervals, leapfrogging up the hill at 1.5 meter increments.

Leanna, Maegan, Natalie, and Ingrid risk limb (if not exactly life) calculating the rise of the cliffs leading up to camp.

Everyone practiced using the Jacob’s staff while scrambling up the sides of the butte that runs up to camp along the banks of the Turkwel. Despite some precarious ridges and loose scree, everyone managed to get the height of the hill. Measuring in three-dimensions. Check.

Ana, Tim, and Ashley picked a particularly steep section to measure and needed to hang the Jacob's staff off the ledge to accurately calculate the height of their perch. Geological dedication is ending the day covered in dirt.

The next day the hiking and navigating skills were put to the test. Dr. Feibel read off a list of directions that simulated the kind of information most geologists start with when searching for a new outcrop. The course was a combination of vague instructions (“walk along the fence line”), cryptic landmarks (“go to the top of Cell Phone Hill”), and compass points (“Walk North 5 degrees West to the river”). Teams set out into the desert, climbing hills, crossing plains, and wandering the gullies and river in a race against time and each other. Everyone made it through the course using compasses and GPS to track their progress with Ingrid and Sam sprinting through the course and Marcel and Francis running sweep with a more methodical style.

Using the GPS tracks, we uploaded the routes off all the groups to Google earth to compare different theories of distance and direction. The red line is 0.5 km. The Turkwel River flows north of the Institute and the badlands we explored the first day with Craig caused all the wandering tracks along the western portion of the course.

Successfully making it home from a hike. Check.

Now it was time to use the compass, GPS, Jacob’s staff, mapping skills and a little math to map a cross-section of the Turkwel River and calculate the volume of water that makes it’s way from the Turkwel’s source at Lake Baringo to Lake Turkana.

The Turkwel River, once a seasonal waterway is now kept constantly flowing thanks to a dam upriver that regulates flow throughout the year.

The river is kept constantly flowing, even during the dry season, by a dammed reservoir upriver. It’s a wide riverbed for the water to spread over and the channel migrates daily, gouging new troughs and cliffs. Each group found a different cross section to map and each group discovered a different river. Some never got their knees wet while others almost treaded water to get an accurate water-depth. Combining information on water depth and velocity, everyone zeroed in on the amount of water that flows by TBI each year.

Poppy, one of the Institute's furriest residents, stresses on the riverbank while the field school students wade into the current.

While at the river, we looked at the cross-bedded sands, channel lag deposits filled with large stones, and floodplain along the banks. These structures were compared to the Holocene (maybe a only a couple thousand years old) sandstone cliffs formed in the badlands visible from camp and the older, Pliocene (maybe 4 million years old) rocks further inland. By comparing the river, the Holocene, and the Pliocene, the full story of the Turkwel’s slow evolution came into focus, a process akin to the step-by-step evolutionary images of apes slowly getting to their feet to become modern humans. Rarely do geologists get to see the modern system so close to its ancestral stock to help piece together the full process.