The shifting scale of geological inquiry can give you spatial and temporal whiplash. You go from scrutinizing a tiny quartz crystal to trying to sort out the arrival of a massive inland sea or go from contemplating a single layer of ash that took a few minutes to fall to an entire formation that took millions of years to settle.

One way to hold all these scales in mind is sit for hours in quiet contemplation of scientific manuscripts. Alternatively, you can speed things along by laying hands on the rock you’re interested in. Fortunately the whole point of being in the Turkana Basin is to get into the the field to hold the rocks rather than read about them.

Meg hefts a fragment of rock from a seasonal riverbed. Like any good geologist she tries to sort out what it is, where it came from, and what it tells her about the entire region. It turned out we needed to smash it to sort it all out. Also the sign of a good geologist.

With all the geological skills necessary to sort out the basic tale of whatever outcrop Dr. Feibel drops us onto, we piled into the truck for Kabua Gorge, an underexplored exposure about two hours north of camp to figure out the recent history of Lake Turkana.

Kabua Gorge is one of the western-most sites preserving evidence of Lake Turkana’s dynamic recent past. In case you lost track of time, our current geological epoch is called the Holocene (or the Anthropocene, but more on that in a later post).

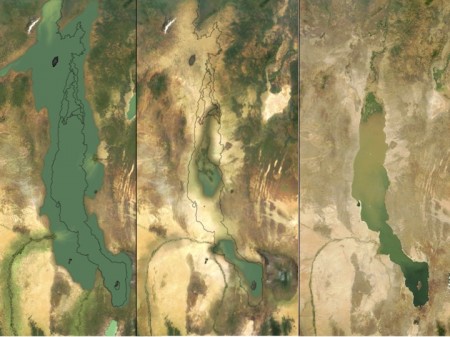

In the early Holocene, about 9,000 years ago, Africa was a pretty well-watered place with grasslands across the Sahara Desert and a gigantic Lake Turkana. Then 4,000 years ago, as the Great Pyramid of Giza was being built, things started to dry out and Lake Turkana lost its water supply. The lake is only about 30 meters deep today, and loses 3 meters of water to evaporation per year, so it needs a constant influx of new water from the Turkwel, Kerio, and especially the Omo rivers to stay filled.

When the water levels dropped 4,000 years ago, the lake split in two with measly northern and southern lakes receiving a trickle of water. Fortunately for the people and animals reliant on the freshwater supplied by Lake Turkana, the depression refilled, leaving the modern shoreline of Lake Turkana.

Left) Lake Turkana 9,000 years ago when it was at the highest level it's ever sustained. The outline of modern Lake Turkana is superimposed. Center) The lowest point Lake Turkana has ever reached. 4,000 years ago the lake lost a major water source and split into two sections leaving the area in the middle, which includes Central Island, high and dry. Right) The modern shoreline of Lake Turkana. The river that starts on the bottom left and swings east is the Turkwel River. To the north is the Omo River, the source of 80% of Lake Turkana's inflow. (Images created by Patricia Schwindinger and Dr. Craig Feibel)

At Kabua Gorge, the sediments underfoot record the rapid expansion of Lake Turkana in the geologically recent past at 9,000 years ago and our task would be to study the evolution of the lake as the waters rose and fell and report back to Dr. Feibel and the rest of the class on the rocks, structures, and fossils found in each section, combining each group’s work to tell a single story of rising water.

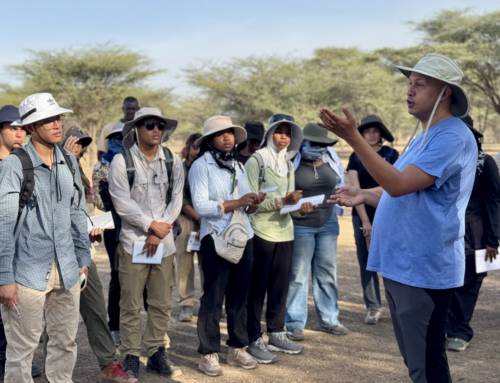

As we approached the site, the landscape quickly changed from the relatively flat desert to rolling badlands and sheer cliffs. Hopping from the truck, sandwiches packed and hiking boots on, the class divided into three separate groups to tackle three different sections of the gorge and different portions of the “Holocene High Stand” lake.

Eve, Ashley, Bailey, Francis, Aaron and Rachel headed into the clay deposits near the eastern part of the gorge, the former lakebed for the vast, ancient Lake Turkana. They found evidence for seasonal pulses of sediment deposition with coarse sands (usually carried by rapidly flowing water) layered between fine clays, evidence of quieter moments in the middle of the lake when floods and rain weren’t dragging a lot of material out to the deep waters.

Eve stretches to provide the scale necessary to sort out the fluctuations in grain size in the bottom of Super Lake Turkana.(Photo from group)

Sam, Holly, Marcel, and Cory scrambled through a series of gullies and ridges to study the rocks laid down 9,000 years ago closer to the shoreline. Small snail and oyster shells crammed into the strata along with evidence of some river systems that cut across the section when the shore retreated.

Holly strikes a 19th century exploratory pose while Sam grins next to evidence of human activity in the area (the nearby water tanks were a subtle clue). (Photo from Cory)

Finally, Rosie, Meg, Maegan, Tim, Acacia, Ana, Rob, and I scrambled up into the lava flows furthest from the modern lake in search of the former beach line of Lake Turkana. The approach required a labor-intensive stroll through loose sand in a modern laga (seasonal riverbed) past massive sheets of volcanic rock that had once blanketed the landscape. As Africa shifted and East Africa tried to make its escape towards the Indian Ocean, the flows were uplifted, leaving frozen waves of basalt rippling to the horizon.

Tim contemplates a fragment of rock that tumbled from somewhere up slope and may tell us about the faulting system that tilted and uplifted the cliffs around us.

The beach was deposited on the tilted, solidified lava millions of years after the volcano that spewed the dark material quieted down. Fossil fish, mollusk shells, and bits of turtle poked out of loose, course sand that would make a decent place to sip fruity tropical drinks while watching the sunset over the lake if ever Lake Turkana ever comes surging back to its ancient shoreline.

Field students to the left, faulted lava flow to the right. Remember that stuff about geology being a science of scale?

Rosie examined faulted blocks of basalt lining the ancient beach. The dropping basalt blocks created the low-points for the lake to fill in and the evidence of the move is written in ground-up basalt and discolored ancient lavas. Maegan and Acacia continued to search for fossil material along the ancient beach.

A tiny rodent mandible (center) spotted by Rob as we crawled the sands looking for terrestrial mammals that may have been buried along the beach line.

Meanwhile Tim, Ana, Rob, Meg, Francis and I employed the ancient geological technique of climbing to the highest point possible to figure out what’s going on. On the uplifted slope, we found more evidence that the rocks had dropped into their present positions and tilted over. From above we could follow the elevation that would have rimmed the ancient lake before it cut back across the basin and settled into its present hole.

Promontories of lava bend into the sand, the columnar fracture revealing the orientation of the cooling material. Our target beaches line the background and serve as the source of the sands that concentrate the water exploited by livestock in the area.

It should be noted that this entire project is basically new and the interpretations the students came up with to explain the rocks they observed are the current working hypothesis for the evolution of the lake through this time period in Kabua Gorge. No higher authority has stepped in to say it’s wrong. Their interpretations are as valid as any interpretation from a “real” geologist and will be treated as legitimate hypotheses with useable, expandable data.

Young local shepherds wandered up the laga to try to figure out what we were seeing in the rocks they walk past on a regular basis that could hold our attention.

Walking and mapping new rocks and sorting out the history of the rocks underfoot; not something easily done at home, but there’s so much to be done in the Turkana Basin that the students on the field school can’t really avoid contributing to the broader understanding of this dynamic environment from the tiniest sand grain to largest body of water this part of the world has ever seen.