Fossils usually aren’t very pretty when they come out of the ground. They’re usually caked in sediment or broken into tiny pieces that need to be reassembled. After they’ve been cleaned and put back together, the fossil is ready for interpretation, description, and display. Easier said than done.

A scrappy-looking hippo mandible found in the badlands just west of camp. The crowns of at least four teeth are preserved, but they'd be tough to study in this condition. This is where a skilled preparator steps in.

The process of getting a fossil from a fragment poking out of a block of collected sediment to the stage where it can be studied is called “fossil preparation” or simply “prep” and a careful preparator is an essential member of any fossil hunting team. Preparation takes a steady hand, a brilliant mind for spatial relationships, and deep wells of patience.

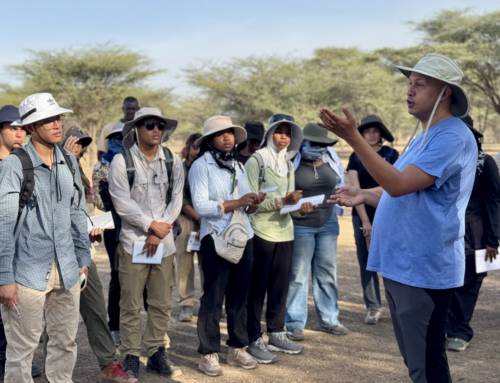

Dr. Meave Leakey discusses the process of finding and identifying fossil hominins in the field. This specimen was buried with only a few teeth poking out of the sediment. After a little careful work, the full mandible emerged.

Throughout the paleontology and paleoanthropology modules, Dr. Meave Leakey has been lecturing on the discovery and assembly of some of the Turkana Basin’s most famous residents such as KNM-WT 15000 or “Nariokotome Boy,” the most complete specimen of Homo erectus ever found. His skull was a mess of fragments that needed to be carefully glued back together and cleaned, a process that took years to accomplish.

More recently, Dr. Leakey and her colleagues published an article in Science on the mandible of Homo rudolfensis. The beautiful fossil jaw began as a non-descript chunk of sandstone that her field crew leader, Niyete, spotted among the rocks. The fossilized teeth and bone were coaxed from the rock by Christopher Kiarie, the lead preparator at TBI.

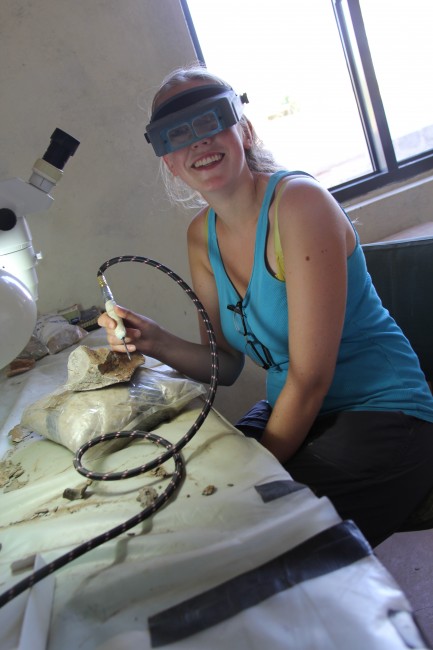

As part of the vertebrate paleontology module, the students were each given a chance to try their hands at a little preparatory work under the guidance of Christopher. Several student worked on fossils they collected at Lothagam earlier in the week.

Ana carefully applies a special fossil glue to the ankle bone of a hippo discovered the day before at Lothagam.

The prep lab on the first floor of the TBI research building sounded like an overbooked dentist’s office as six students at a time bellied up to the bench, grabbed a pneumatic sanding tool called an airscribe, and a tube of glue. Slowly the rough hippo molar Rosie was working on emerged from the sandy cement and the irregular chunk of long bone Meg was working on began to look more like articular bone and less like rock.

Francis also assists with the fossil preparation at TBI. He was present for the excavations of Nariokotome Boy in the early '80s when he was a little kid and hasn't stopped working with fossils since.

Now that the grit was cleaned off and the fragments of bone reassembled, each bone or fragment was given a number, a tentative identification, and a place in a catalogued specimen drawer for future study.

Behind the scenes at every museum there is a vast collection of drawers holding thousands – maybe millions – of fossils bits that aren’t much to look at and don’t make it into the displays, but can be a precious resource to a paleontologist with the right questions. Throughout the week, the students had been working on formulating their questions based on the material we’d collected, and their results were a testament to their new analytical skills as paleontologists…