As part of the TBI Field School students get to work on new fossil material. Well, maybe not “new” in the normal sense of that word, but they get to work with material that no one else has laid hands on or thought about because it just came out of the ground a few days ago.

An unworn hippo tooth just scooped off the ground. No one else has thought about this tooth. No one has tried to figure out how big the animal was, how old it was, or what species it belongs to. This "new" fossil is an opportunity for a TBI student to delve into the fossil record, going where no one else has tread.

Dr. Fortelius’s research focuses on using fossils, especially teeth, to tell us about changing climates and environments through the chaotic Cenozoic and the methods he taught in lecture and lab generated student insights into the material.

Armed with new fossils and new techniques, several students saw the fossils collected at Lothagam and at Kangatotha as a chance to answer their own questions as part of independent student research projects that were presented at the end of the paleontology module. These aren’t simple student reports. This is real science.

Dr. Fortelius opens the independent research presentation seminar which marks the end of the paleontology module and the start of our final two weeks in camp.

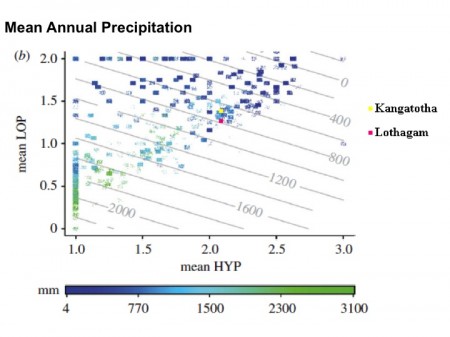

Eve and Bailie examined the shape and size of the teeth collected at Lothagam and Kangatotha to reconstruct the climate and precipitation at the two sites. Dr. Fortelius has been doing these reconstructions in Eurasia for many years, but has a more limited sample of African localities. He’s working on building his African database and Eve and Bailie’s work directly contributed to the broader understanding of Africa’s rapidly changing climate over the last six million years.

Kangatotha (yellow pin) and Lothagam (red pin) marked on a map of Lake Turkana. The Turkwel River flows from the south (the bottom) and curves nearly 90 degrees east to the lake. TBI is a little west of Kangatotha on the Turkwel River.

Even and Bailie found the dental diversity at Lothagam was consistent with a tropical grassland environment, a result other workers had suggested based on the fossils recovered from the site. They also used the few animal dental remains recovered from Kangatotha to propose the first climatic reconstruction of the newly worked locality. They found the dental remains consistent with the temperature and precipitation of a shrubby desert. The fragments of human remains recovered from Kangatotha now had an environment to move through. But who were those people?

Precipitation levels were reconstructed as pretty low based on the dental diversity found at Lothagam and Kangatotha. These are preliminary data, but they seem consistent with other measures of climate used to piece together the environmental history of the Turkana Basin.

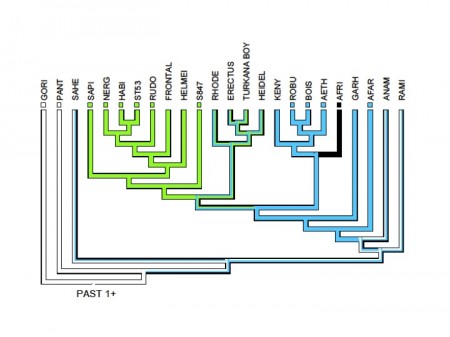

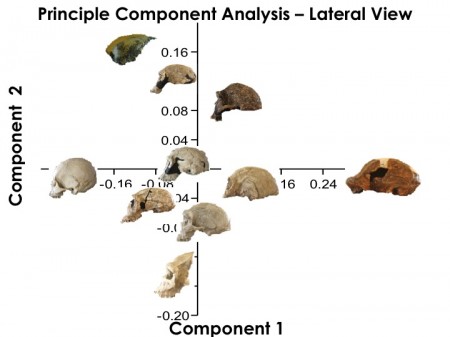

John and Cory decided to tackle that question. They examined the two skull fragments we collected at Kangatotha and included the mystery hominins in a cladistic analysis, a method of establishing the closest relatives of specimens by scoring them for a list of traits. They used a character list provided by researchers who study human evolution, Dr. Fred Grine and Dr. Heather Smith, and added their own new characters. They also performed a morphometric analysis, comparing the shapes of the skull fragments to the skulls of other extinct and living hominins. Their preliminary analysis suggests the Kangatotha skull fragments were not from fully modern humans, pushing the age of the site way past the Holocene age we originally thought we were working with when we first set boots on the ground north of the Turkwel.

Using landmark based morphometric analysis, John and Cory found the lateral frontal fragment (upper left) was similar to modern humans in some aspects of its shape (far left), but was more robust and similar to Homo rudofensis on the second axis of shape variation (just below 0.16). A result consistent with an archaic species from our own genus.

Maegan and Rachel also worked with a Kangatotha mystery. On the last day in the last hour at the site, Maegan found a fragment of a sacrum, the bone that sits at the base of your vertebral column and forms the keystone of the pelvis.

The Kangatotha sacral fragment. The wide, compressed vertebral articulation (facing us in the center of the upper image) lead Meagan to question the field identification of the specimen.

In the field we made a tentative identification of the element as a human sacrum, but the ID didn’t sit right with Maegan and Rachel who set out to figure out who the sacrum belonged to with the limited comparative sample available at TBI. They tracked down images of extinct human sacra and looked at the hips of a chimp, camel, baboon, and cat. Nothing seemed like the perfect fit.

Maegan and Rachel measuring the shape of different pelves from the human fossil record while comparing the fossil sacrum to the limited osteological collection we had available.

After some inconclusive measurements, they noted the similarities between the small cat sacrum and the large fossil. After spending some time with osteology books on African mammals they discovered the “hominid” sacrum of Kangatotha likely belonged to a big cat like a lion or maybe even a sabre-toothed cat. This was a very old-school paleontological analysis based on careful observations and comparisons with other bones. Sometimes there’s no school like the old school.

Meagan demonstrates the sacral characters that lead her and Rachel to hypothesize the fossil belonged to a large felid.

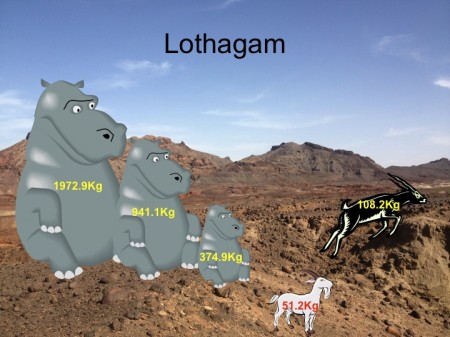

Ingrid and Natalie were also able to draw on the material collected at Lothagam in their analysis of body size reconstructions. As Dr. Fortelius pointed out several times in lecture, body size is the single most important factor when a paleontologist or biologist is trying to sort out the lifestyle of an animal. Body size and mass are directly related to metabolism, diet, reproduction, and locomotion. Over the years, paleontologists have tried to use every scrap of preserved bone to reconstruct the body sizes of ancient animals. Some are more accurate that others, and Ingrid and Natalie tried to figure out which gave the best estimates and what range of estimates were reconstructed by different equations. They then applied their reconstruction methods to the material collected at Lothagam and found a reconstructed range of body sizes for the hippos and bovids we collected only a few days earlier.

Body mass reconstructions by Ingrid and Natalie are based on the limited material recovered from the fossil hill crawls. The range of hippo sizes may reflect that range of sizes in a single species, but the more likely scenario is we have multiple hippo species present at Lothagam, something we know from looking at hippo dental diversity at the site.

Ana was also interested in reconstructing body size, but chose to focus on vertebrae, an important part of an animal’s structure that has received very little attention from paleontolgists interested in body size, partially because complete vertebrae don’t preserve very well. However, Ana did find it was possible to estimate body mass accurately based on several linear measurements of different parts of a mammal’s backbone.

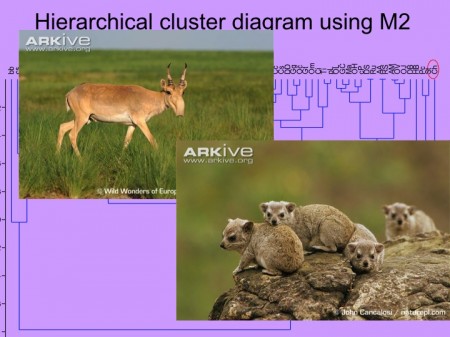

The next group of students were interested in using the methods developed by Dr. Fortelius to reconstruct diet based on the shape and wear of teeth. Meg and Sam used samples of modern goat teeth collected around TBI to figure out if their teeth recorded the actual diets of the browsing and grazing domestic stock. Their analysis worked beautifully. They found the goat’s teeth recorded a mixed feeding population and the goats of South Turkwel had diet comparable to browsing/grazing siaga antelope and hyraxes.

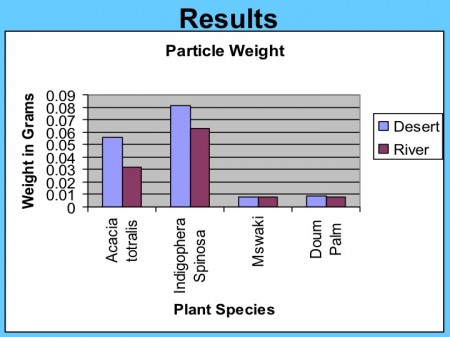

Aaron and Rosie focused on the reasons for the wear observed by Sam and Meg by collecting plants from around the compound, the river, the road, and nearby clearings. They wanted to know how much grit and dust is carried by plants consumed by goats. After several attempts to get dust strained from foliage, they finally discovered Indigofera, the ubiquitous spikey shrubs that the goats enthusiastically graze, also carries a lot of dust making it tough to figure out if the wear on the goat teeth observed by Meg and Sam is related to inorganic grit or the organic, gritty properties of the plants the goats munch.

The amount of sand and grit on each plant type was filtered off and weighed. Indigofera won the dirtiest plant award by a long shot.

Marcel was also drawn in to goat tooth questions because of the sheer abundance of the things. Every time we go to the soccer pitch, we collect anther half dozen jaws and skull fragments to add to the comparative collection that is growing in the South Turkwel collection. If you know anyone searching for a population of desert goats to study, refer them here.

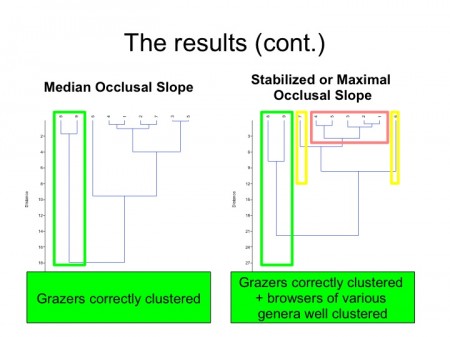

Marcel did not have a very extensive comparative sample, but he did find a possible method for reconstructing the diets of herbivores based on the angle of wear on goat and camel teeth.

Marcel wanted to see if he could establish a new measurement for reconstructing diet. He settled on the slope of dental wear and found – after a long time collecting angle measurement from molars – a decent correlation between diet and slope.

Marcel gets his goat. Each goat individual wears its teeth slightly differently. Trying to sort out the relationships between dental shape, dental function, and the evolutionary inheritance of the animal leads to a lot of head scratching. But that's the fun of paleontology.

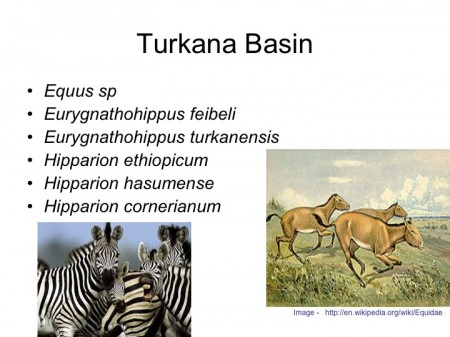

After so much discussion of teeth and body size, Francis wanted to figure out the connection between the two. He wanted to examine dental variation in extinct horses found in the Turkana Basin. After a lot of number crunching and regressions he found there were distinct differences in both aspects of the skeleton in the horses that proceeded the zebras we see in East Africa today.

The different genera and species of horse found in the Turkana Basin, some with three toes, like Hipparion, and some with only one like the modern horse and zebra.

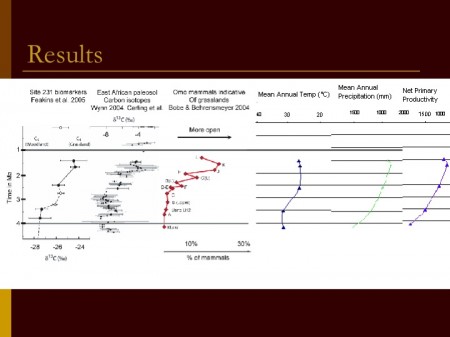

Holly’s dental project used teeth as proxies for reconstructing climate fluctuations in the Turkana Basin. She used a database Dr. Meave Leakey and Dr. Fortelius have been collaborating on to reconstruct the spikes in temperature and humidity also found in the isotopic record.

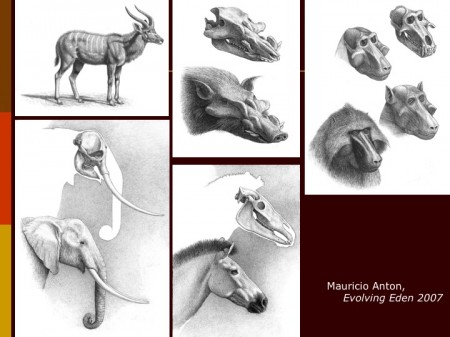

Herbivores of the Turkana Basin. Holly and Dr. Fortelius can use the dental variation of these animals to figure out a variety of climatic variables that help reconstruct the changing East African environment through the Neogene.

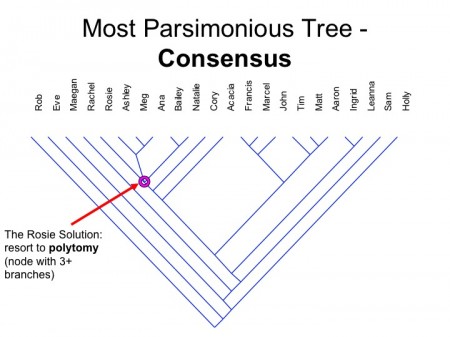

Leanna opted to use the systematic techniques introduced during the vertebrate paleontology to score and categorize a really weird group of organism: us! She designed a series of questions that she asked each student and TA then translated her results into a character list like a paleontologist studying variation in the skeletons of different animals. Her phylogenetic tree then clumped students based on shared traits both biological (shoe size) and personal (do you have a tattoo?). Suffice it to say, the results made everyone smile. And we learned about cladistics to boot.

TBI Spring 2013 student phylogeny. Note the clade of guys (except Rob). Leanna did not include gender in this analysis, but other traits seemed to recover synapomorphies of the TBI men (such as shoe size and no body piercings).

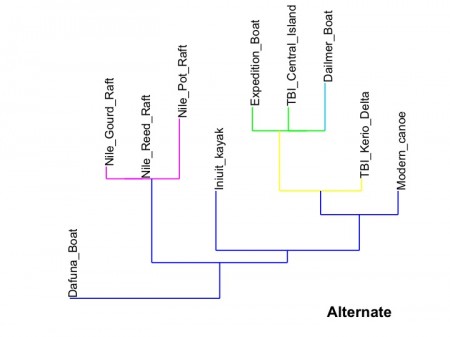

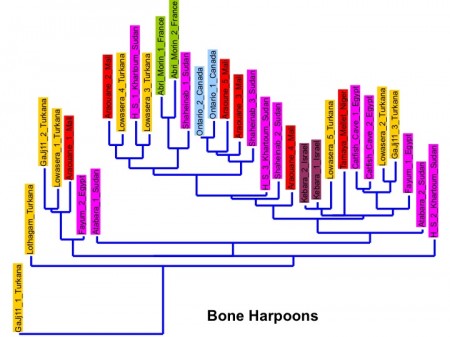

Tim and Ashley wanted to take the same cladistic systematic techniques usually reserved for biological questions and apply them to the archaeological record to see if known cultural connections between groups would clump the way related animals clump.

Ashley took her interest in boats to a new level by digging through the available literature on the boats of the Turkana Basin and the Nile River Valley to reconstruct a phylogeny that echoed the known cultural exchange through East Africa. Tim had less luck getting harpoon points to track their known temporal and geographic ranges, but he now has the analytical tools to tackle other relationships in the archaeological record.

Tim harpoon phylogeny Tim reconstructed. The colors represent geographic regions which clearly aren't being recovered by this phylogenetic analysis of harpoons though there may be information on function and cultural convergence tucked into these data.

After hours of research and analysis, the students presented their results to one another. The presentations were fantastic. Many could easily have been presented at a professional meeting after a little more time for data collection.

For the final, each student sat with Dr. Fortelius and an assortment of fossils. They were asked to identify the material and speculate on the biology of the fossilized material, an ability few students had before the module began. Most handled the task effortlessly and only needed a few nudges in the right direction to make a successful identification. Now that we had an understanding of the environment that surrounded our earliest ancestors, it was time to turn our full attention to the apes that opted to walk on two legs and started the fascinating lineage that meandered its way to us…