The Turkana Basin if famous for preserving the fossilized remains of our bipedal ancestors. But, there are more than fossil hominins in the rocks piled up around Lake Turkana. The remains of horses, pigs, fish, hyaenas, and hippos (lots of hippos) also tumble from the rock, providing the ecological and environmental context for the evolution of our own lineage.

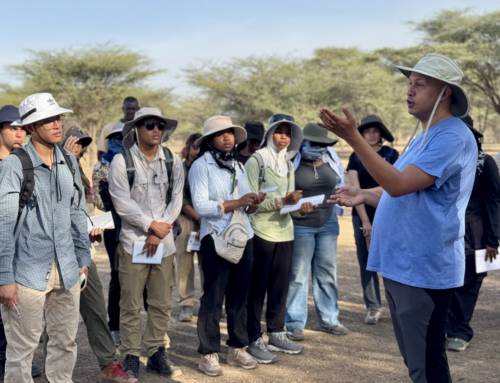

Our guide through the extinct and evolving African ecosystem is Dr. Mikael Fortelius from the University of Helsinki. He has worked on many projects across Europe and Asia and is just beginning to explore the vertebrate record in east Africa. Throughout the course, Dr. Meave Leakey worked with the students as well. She has spent her entire career focused on the evolution of African faunas over the last 10 million years. So, we got to watch two new scientific collaborators share their knowledge and insights with one another in real time as each gained new insights from the others unique store of paleontological knowledge.

Dr. Mikael Fortelius and Maegan discuss fossils of the Turkana Basin. Especially teeth. Especially hypsodont herbivore teeth.

The course began with piles of fossils and bones. The students moved around the room, identifying what they could and speculating on what they could not. By the end they would be able to look at the small piles of stones and bones and conjure up grazing pigs, running hippos, and slender-snouted crocodiles.

Leanna, Sam, and Marcel contemplate fossils and bones. Leanna had a moment of revelation about the Euthecodon maxilla as the shutter snapped.

But before we could learn about the strange menagerie that has moved through the Turkana Basin, we had to think about time. It’s unavoidable. Every module we have tackled – really all of sciences that could be lumped into “natural history” – depends on an understanding of the geological timescale. Having a working idea of the scale is key to understanding the ever-shifting continents, climate, and diversity of species.

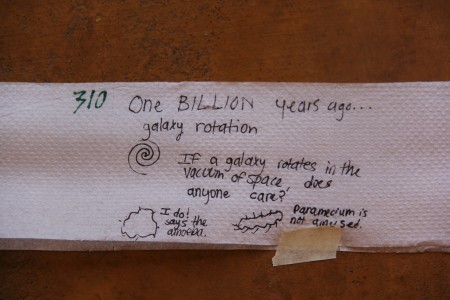

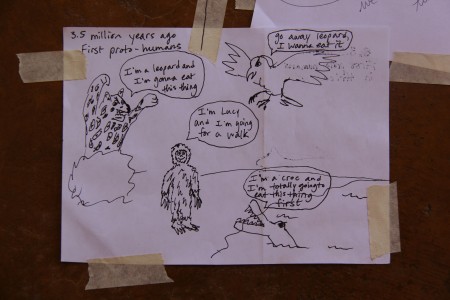

It’s a lot of information to simply memorize so we built a scale model of the earth history to make the massive swathes of time more concrete (or at least papery). Using two rolls of Kenyan toilet paper (durable stuff), two groups of students laid out and illustrated a scaled history of the planet from its formation to the present.

The closer we get to the present, the more animals radiate and disperse. The Cenozoic ended up with the timescale needing extension sheets for the closely packed inside jokes and art.

What emerged was a lot of blank space for a long time as the planet formed 4.5 billion years ago, cooled and the first single-celled bacteria plied the primordial oceans starting 3.5 billion years ago. And nothing particularly exciting happened for a very long time, at least, nothing that gets vertebrate paleontologists jazzed. Chemically, revolutions were taking place as the genetic code used by every living organism on the planet was refined, cells increased complexity, and microscopic ecosystems started to take shape. A little more than 500 million years ago, billions of years after the formation of the planet, multicellular organisms took off.

Another busy Phanerozoic. In the foreground the Cambrian explosion is in full force at Tim's toe with multicellular life radiating into all major categories of animals. In the distance pangolins and creodonts make their later appearances. Front to back: Tim, Ashley, Natalie, Ingrid, Marcel, Ana

The students walked the paper and illustrated the important events along the timeline, trying to cram the origins of primates, apes, and hominins into the last sliver of toilet paper. All that fascinating stuff geologically happened so quickly…if you consider a few million years quick. In the grand scheme of the history of life, we are new arrivals. Or maybe you consider us fashionably late.

Ashley made sure the timescale ended with the most recent event and the culmination of earth history: the TBI Field School.

Along with the timescale and a sense of the whens and wheres of a fossil locality, a vertebrate paleontologist needs to constantly be thinking about what the record is actually saying. Just because a horse tooth is preserved next to a lion’s jaw, we can’t jump to the conclusion that the horse and lion died during a bloody confrontation. Maybe they were washed into the same channel in the stream or maybe one is more heavily eroded because it traveled a long way before finally entering the fossil record.

The study of how pieces of living creatures are used and abused by the environment before becoming fossils is called taphonomy. In order to study the process of materials entering the record and weathering out of the rock, the field school planted fragments of ceramic plates, bowls and pots in the ground for future field schools to analyze. We started with the complete objects, documented their shapes and colors. Then smashed them.

The final result of the experiment. There are a few discernible "taxa" on the table to be reassembled.

The shattered table settings were then reassembled from the jumbled mass of shards in the middle of the table, a demonstration that cracks, colors and subtle shape changes are plenty of information for putting the story back together.

The field school puzzle club hard at work trying to reassemble the fragments. Puzzle masters left to right: Cory, Francis, Ingrid, Ashley, Rosie, Sam, Maegan, Bailie, Acacia, Eve, Natalie, Rob, Aaron, and Tim

But we didn’t just use any old ceramics. While brainstorming this taphonomic experiment with Richard Leakey, founder of TBI, and Lawrence Martin, director of TBI, Meave Leakey realized she had a few extra saucers and pots stuffed away in the attic that could be put to good use in the ground. The original owner was Mary Leakey, Richard Leakey’s illustrious fossil-hunting mother. Mary had used the plates and bowls in camp at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania and the objects were present for some of the most important early discoveries in East African paleoanthropology including the excavation of Zinjanthropus (now Paranthropus) boisei and the Laetoli footprints (3.6 million year old evidence of our bipedal ancestors walking across a preserved ash field).

Mary Leakey’s coffee pot was documented as we would any other fossil. But instead of preserving the artifact, we put it into the ground.

We reverently unwrapped the material, unsure if we were about to destroy objects that should really be in a paleoanthropology exhibit. Meave assured us Mary would have wanted her old plates to be part of an experiment on fossilization and would have been the first to bring the hammer down for science. So we smashed.

Meave and Eve at the pottery burial. According to Meave, this is exactly how Mary would have wanted her plates to be used.

After scattering the fragments and burying them in different layers of strata, we headed back to the lab to spend a little bit of time examining the osteology collection at TBI, comparing a skull of a giraffe to the skull of a camel and a rhino. Dr. Fortelius made sure we paid special attention to the complex teeth, implying we may be spending a little bit of time in contemplation of teeth through the course of the module. It was also important to start to learn how to recognize the anklebones, vertebrae, and dental fragments of the modern taxa housed at TBI so when we could head into the field with a better search image for the progenitors of the modern African fauna.

Ana and Rosie discuss the sheer size of sauropod (long-necked) dinosaurs. The thing in the foreground is a tail vertebra. This material is from Lapurr, a locality preserving rocks from the Age of Dinosaurs on the Northwestern shore of Lake Turkana. The site is worked on by TBI researcher Joe Sertich from the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

Note: I’m behind. Very behind. But that doesn’t mean I won’t be documenting the full TBI field school experience. You may or may not know that the students are leaving TBI in one week. I will continue to update the blog until the entire story has been told. If you are curious, please continue to visit until I write about graduating from the program. Back to vertebrate fossils…