In Kenya, rain is a blessing. It is something to celebrate if you have rain on your wedding day. If rain is a blessing, then nature wanted to shower the last few days at the Turkana Basin Institute with signs that this was a blessed experience.

The gathering storm looming over the Turkwel River. After weeks of clear blue skies and soaring temperatures, our final days in the Turkana Basin Institute would be a little wet and a little brisk. Photo taken by Acacia.

As Dr. Matt Skinner from University College London brought the human story to a close, the storm clouds gathered. We discussed the complex evolution of Homo sapiens, a species finally marked in the fossil record with the debut of a chin, reduced brow ridges, and a smooth, high-vaulted skull. This new hominid appears in Africa around 200,000 years ago and begins to spread out of Africa around 70,000 years ago. By 50,000 years ago the behavioral artifacts we associate with modern behavior – art, complex tool kits, burials and grave goods – are in place and we barreled on to the present.

Recorded history started 6,000-ish years ago. If Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt seem like a long time ago, imagine the depth of prehistory. We only have a written record of 0.03% of our time on earth – and most of that is from Eurasia. The other 99.97% of the modern human story must be uncovered by archaeologists working on the origins of our mixing, making, and meandering species.

Ahead of the storm, a massive gust of wind charges across the desert, picking up sand and dust. The storm dramatically demonstrated the energy of the rains that pummel the outcrops each year. This is why many fossils found on the surface are fractured or broken and why new stuff is being found all the time. After each rain storm the badlands have new material sticking out of the cliffs for paleoanthropologists to search out and collect.

As Dr. Skinner’s lecture neared the present, the wind started to pick up and the cloudbank we had seen that morning had turned into a black wall churning towards TBI. The doors and windows around the compound started to slam and we ran around the cottages, dorm, and classroom battening down the hatches. The powerful gust of wind carrying sand and dust from across the basin then hit with its full ferocity. The students tried to dance in the rain but found out the rain was less fun when you were getting sandblasted at the same time.

Aaron and Rachel watch the storm slam into TBI. The streams of water running off the research building next to the classroom created miniature gullies in the sand, tiny replicas of the larger badland excavations created by millennia of rains eroding the fossiliferous sandstone of the Turkana Basin.

The rain fell in torrential sheets with the water scouring the sand and rutting the camp with deep rivulets. Meave had told us that a new visit to an old locality has the possibility of new discoveries because the rains can erode so much material in a single rainy season. I hadn’t been able to imagine that much rain being blasted with such power in such a dry desert where laundry dries in less than an hour.

Now I can imagine entire hominin skeletons weathering out of the sandstone in a single storm, then the fossil getting pounded by the rains until there’s nothing but scrappy fragments for the observant fossil prospector to discover the next season.

Rain streaming off the classroom building. The strange weather and subsequent eruption of insects in the wake of the newly arrived moisture added new challenges to the already stressful task of preparing for the final exam and presentations in Paleoanthropology. Fortunately, we have adaptable students in the Turkana Basin.

Our final day in camp was packed, starting with the paleoanthropology final exam. The coursework for the TBI field school is equivalent to graduate student courses, so some serious studying needs to happen. One of the side effects of the rain in the desert is the whole place erupts with life, especially insect life. As the students tried to study in the mess hall, bugs rained onto notebooks as the creatures swarmed the overhead lights. As the night wore on, a group of studiers retreated to the classroom and closed all the windows and doors to get some relief from the bugs (but not the heat). The insects provided a back-up percussion groove as they slammed against the windows while trying to get into the room to buzz the light bulbs. These are the hazards of studying for an exam in the field!

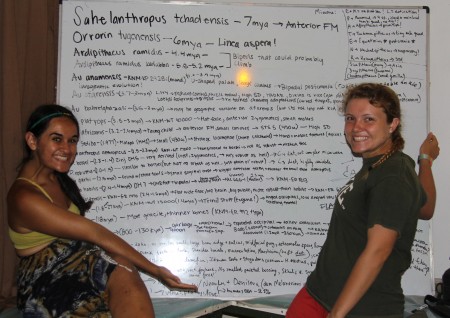

Eve and Ingrid with all of human evolutionary history crammed onto a single dry erase board. Note this was put together as newly-arrived insects brought in by the storm slammed themselves against the windows and flung themselves at the lights, bringing on the bats. Not your typical paleoanthropology study session.

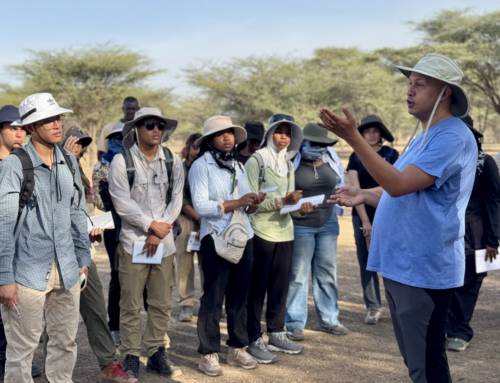

After the exam the students presented their lectures for our final (that word again) seminar of the season. Instead of taking on independent research projects – the labs created by Dr. Skinner facilitated a lot of inquiry into the hominin material in camp – the students were challenged to pick a popular question asked by non-paleoanthropologists about human evolution and try to answer that question using non-technical language and illustrative demonstrations. Questions like, “How do you know that fossil is 2 million years old?” or “Are humans still evolving?” The rest of us were supposed to pretend we were a audience of curious non-specialists to continue the discussion.

Leanna started by illustrating our specialized abilities as runners, an ability no other primate pulls off with our speed or endurance. We may not have big claws, big teeth, or impressive plumage but we can move. Rachel dove into the complicated question of human violence and intraspecies violence in other animals. She was especially interested in exploring the implications of stomach-churning violence in our closest living relative, the chimpanzee. Natalie explained that despite some Neanderthal genes in most non-African populations, there are no extant examples of Homo neanderthalensis, despite how some women may feel about their husbands. Ana discussed the question that drew us all to the Turkana Basin: Why are there so many fossils in East Africa? Thank you Rift Valley.

Interspersed through this section of the post are portraits of the students at graduation where Dr. Leakey congratulated each of them on a job well-done over the previous ten-weeks and gave them each a certificate of completion. A fancier, card-stock version will be sent out in the next few weeks, just like a university graduation.

Many people ask questions about the origins and importance of vision and hearing, but Holly wanted to discuss the origin an importance of our well-developed sense of touch. Sam tried to explain Darwin’s great insight, natural selection at work in living populations, in ten short minutes.

Sam took volunteers - Maegan, Bailie, and Natalie - to demonstrate how natural selection acts on a population foraging for lentils in the brush.

Walking on two legs is a feat (pun intended) so natural it’s easy to forget how weird it really is. With our bad knees and propensity to trip, Meg asked why we bother to be bipedal in the first place. Tim struck at the foundations of the scala naturae – the great chain of being – by demonstrating humans are far from the top of the evolutionary ladder. Since all species have been evolving for the same amount of time, we are all at the top of our evolutionary lineages, adapted to the modern environment as best we can be. Ingrid followed the dethronement of humans by answering a question I often hear in museums and zoos, “If humans evolved from apes, why are there still apes?” Different environmental pressures do amazing things.

John looked into the origins and diversity of human tool use, pointing out even the domestication of dogs tells us something about early humans’ ability to use symbolic thought and ingenuity to adapt to the changing world. Cory followed by exploring the definition and origins of human “culture” in the archaeological record. Aaron led an engaging discussion of culture in other animals, demonstrating tool use, art, and language in otters, elephants, primates, and birds.

Meagan asked if we are an evolving species. She pointed out we have vestigial structures such as wisdom teeth, ear muscles, and an appendix that may be selected against, but at the moment aren’t being shaped by many environmental pressures. Marcel explained how speciation works, starting by pointing out that mathematically it is impossible to get two from one but in biology it is evolutionary fact.

Marcel, a Swiss researcher in the process of applying for graduate opportunities, and Richard Leakey

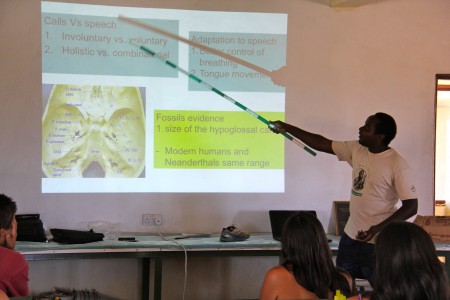

Francis looked into the anatomy and diversity of human speech, showing us how humans create a variety of sounds and how those sounds are arranged into functional language. Bailey took on the thorny issue of race, explaining that biologically there is so much gene flow through our species – and always has been – that it is impossible to identify separate biological races as we might identify subspecies and races in bird populations. Rosie dealt with the tiny, superficial physical variation we do see in human populations and showed how the environment has selected for different shapes and colors. Ashley lightened the discussion by asking, “Why can you hug a dog, but a dog can’t hug you back?” which lead to an explanation of the anatomical basis of our primate-inherited ability to rotate our hands, a talent a dog – and many other animals – are missing out on. And finally Eve closed out our human evolution binge by explaining the delicate balance our bodies have struck between walking bipedally and being born with big brains.

Rosie decided to try to answer the perennial question: If we’re all so closely related, why do we variation in size and shape? Here she’s showing how the environment has molded two different human populations: The shorter, stockier Inuit who are better able to maintain their body temperature by not dumping heat with long limbs, and the lanky Kalahari bushmen who are better able to dump body heat in the desert with a more lightly built frame.

Even wanted to explain to her lay audience the evolutionary negotiation between bipedality and big brains. The hips can only get so wide before walking becomes inefficient. But we need to be born with large brains if we are going to have large brains as adults. The negotiation between the size of the birth canal and the size of our brains at birth has dramatically affected our anatomy and social structure.

Tim, Francis, and Macel talk Kenyan politics in the wake of the Kenyan Supreme Court’s decision to let the election results stand with Uhuru Kenyatta as the new president of Kenya. Ana enjoys one of the last fresh watermelon deserts of the field school. After ten weeks, we all have vast watermelon gardens growing in our stomachs.

After a day spent with the big questions of human evolution – and confirmation that everyone had passed the course – we reassembled at sunset for a graduation ceremony with Meave and Richard Leakey, two people who have spent their lives thinking about – and answering – the big questions of human evolution.

At the graduation ceremony, Dr. Richard Leakey, the man who first saw paleontological potential in the rocks of the Turkana Basin and built his incredible career on the fossils he found there with his expert team including Dr. Meave Leakey, charges the field school to keep up the search for our origins in whatever field they may land in.

After ten weeks of intense coursework and intense fieldwork, Richard Leakey congratulated the third TBI field school on a job well-done. He’s been working in the Turkana Basin for 45 years and he challenged us to make the next 45 even more productive and dynamic. There are a lot of changes and challenges ahead for Turkana. Oil has been discovered, dams are being constructed, and new farms are being seeded. The Leakeys and the larger body of people supporting TBI have established the infrastructure for research to continue exploring the past in the Turkana Basin while also monitoring the modern changes in the Basin. Dr. Leakey also complimented the crew on their adaptability and intelligence. It was a bashful bunch after that one.

The Spring 2013 Field School with the Leakeys, whose focused effort to get to the root of our collective family tree put Turkana at the center of paleoanthropological inquiry. Also in this picture is Francis, our Turkana guide who has been working with the Leakeys since he was a boy in 1985 helping pick through the sediment around Turkana Boy, the most complete Homo erectus specimen ever found. Back: Marcel, Francis, John, Cory, Natalie, Time, Ana, Francis, Dr. Richard Leakey. Second Row: Dr. Meave Leakey, Bailie, Ingrid, Sam, Maegan, Meg, Ashley. Front Row: Aaron, Eve, Rosie, Holly, and Fuzzy.

Then he personally congratulated each student on successfully completing the field school which continues to refine its curriculum for aspiring anthropologists, geologists, and paleontologists.

The Spring 2013 Field School closes out the Paleoanthropology module with a group portrait with Dr. Matt Skinner. It had been a sprint to the finish after two weeks packed with information and debate on the fossilized evidence of the origins of our species. After an exam in the morning and student presentations the rest of the day, everyone had earned their celebratory Tuskers on the final evening. Back: Marcel, John, Cory, Natalie, Tim, Francis. Second row: Rosie, Bailey, Ingrid, Sam, Maegan, Meg, Ashley, Ana. Front: Francis, Dr. Matthew Skinner, Eve, and Holly.

A rainbow appeared in the sky as the graduation ceremony wound to a close. If we needed nature’s affirmation that we had all been through an incredible ten weeks, this was it.

The exams were completed, the presentations finished. A few more celebratory group photos later and the students were released to celebrate ten weeks that flew by in a blur of sunscreen, watermelon slices, and hippo fossil fragments. Tusker toasts and awards were shared and everyone seemed a little shocked that it was all over.

John and the many of the other students signed the Turkwel campus guest book with notes of thanks and advice for future field school students. John even left a sketch of his favorite hominin for future schools.

The next morning the ominous cloudbank was gathering again. As much as we all wanted to linger, we didn’t want to be stuck in the mud between TBI and Lodwar and miss our flight. Goodbye hugs and handshakes for the staff, Richard, and Meave and we piled into the lorry for our final ride of the season.

We thanked the camp staff for taking such care of our lodgings and stomachs for the duration of the school. The facilities were beautifully maintained and I’ve been missing the food for two weeks now and counting.

As we pulled out of the gate, Meave’s dog Fuzzy bolted after us, not wanting to say goodbye to all those belly scratches. We stopped to send Fuzzy back home and continued our journey ahead of the building storm.

The Turkana Basin Institute has just vanished over the horizon. We had to rush out of camp before the storm could slow our progress down the road to Lodwar. As the truck drove through the gate, Fuzzy, Meave’s dog took off after the students, chasing the truck for one last round of ear scratches and pets.

In Lodwar we found out our flight was delayed thanks to the weather that finally broke over the town making this a blessed Easter Sunday. We were given a lingering goodbye to Turkana but it was a soggy, chilly Turkana that caused jackets to be dug from luggage and the canvas walls of the lorry to be unfurled for the first time to keep the rain from pooling on the benches.

Lodwar Airport with water pooling near the runway. It's unclear if these engines are a warning, trophy, or public art.

Our plane finally arrived at the Lodwar airstrip and we watched the looping Turkwel and the sunburned desert disappear behind us. When we dipped back below the clouds, the earth was a riot of green and blue. It was almost too much color to take in at a glance.

Green highlands near Nairobi. This shocking spring scene was unexpected and almost hurt my eyes the first time I glanced out the window.

When we landed at Wilson Airport we were scooped up by the bus that had met us the first day we touched down in Nairobi. Memories of that first day, everyone shy and quiet, finally made me realize how much time really had passed. As we piled on the bus we had to make our first student goodbye as Francis wished us well before going into Nairobi to be reunited with his wife and baby daughter. The rest of us went to the Galleria, a mall near Wilson where we could get lunch before going into the Nairobi airport.

Because it was Easter, there was a little train set up in front of the mall pulled by fiberglass pastel bunnies. Everyone else was in their Sunday best, little girls in frilly dresses and little boys in shiny shoes. We were a bedraggled looking bunch dropped into this scene of springy cleanliness.

We enjoyed our filtered coffee and burgers, and experienced a few minor pangs of reverse culture shock. After a stop at a craft kiosk for final mementos, we had our second goodbye as Marcel took off for Nairobi. And now our bus headed for the airport and our biggest round of goodbyes.

Most of the students were continuing to Amsterdam, but a few were staying back, some for a single day in Nairobi, others for several weeks before they would make it home. For my part, I stayed behind for two weeks to get some research done at the Nairobi National Museum. Even if I would be seeing some of these students again in Nairobi, at Stony Brook, in New York City, or wandering across the Midwest, this was it. The bubble of the field school was burst.

Leanna waves goodbye as she follows her fellow departing students towards security and check-in. But Leanna, like many of the students on the field school, will be back in Africa before long.

As I said goodbye to each of these accomplished undergraduates, I told them to keep me and the rest of TBI posted as they continue their academic and professional journeys. They will do great things and hopefully the lessons learned in the field, in the classroom, and with each other helped them along that journey. I know my path has been affected by the experience. The opportunity to work with the students and researchers at TBI has given me a greater sense of focus and drive as I dig into the origins of African ecosystems and try to teach others about what I’ve learned.

We watched as the departing students disappeared towards security. This was an incredible ten weeks. A beautiful thing. The memories, the pictures, the sand, the thorns, the sunburns, the soggy luggage, and the friends will linger, evidence of the blessings of Turkana to carry home.

The Spring 2013 Field School. Top: Meg, Francis, John, Bailie, Rosie, Eve, Maegan, Leanna, Ashley, Marcel, Rob. Front: Acacia, Sam, Tim, Holly, Cory, Natalie, Ingrid, Ana, Rachel, Matt, and Aaron.

Note: If you’ve been following this blog, thank you for joining us on our journey. If you are a student or researcher interested in what the Turkana Basin Field School is all about, please feel free to contact me at matthew.borths@stonybrook.edu . I will happily answer any questions about the campus, the routine, and the curriculum. I can also put you in contact with the students if you want a participant’s insight. It’s been a lot of fun documenting the field school’s adventures this spring. Thanks for coming along for the ride! – Matt