The Pleistocene is sometimes called the Ice Age, but ice was as rare 2 million years ago as it is today in the Turkana Basin. Instead the glaciers in the north caused the deserts and arid grasslands to expand as the ice advanced and the expansion of the forests when the ice retreated. Our early bipedal ancestors in the genus Australopithecus were plunged into this climatic nightmare and emerged transformed.

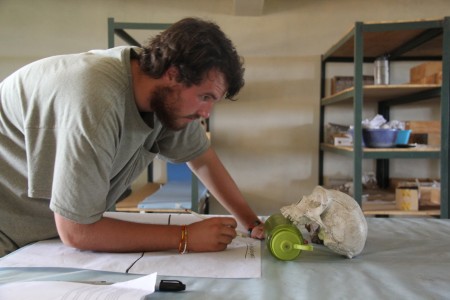

John draws the portrait of Homo heidelbergensis, one of the Pleistocene species that evolved in Africa and probably lead strait to us. This specimen is nicknamed Kabwe for the site where it was discovered in Zambia. Compare primitive features of Kabwe - the shelf-like browridge, the low cranial vault, and the projecting face - to John's modern, thoughtful visage.

It used to be thought this was a pretty smooth transition from the skulking apes to the squatting australopiths to our own lanky genus Homo. But the last few decades of research have shown our family tree is a little more complicated than we thought and is really more of an unruly family bush. The Pleistocene witnessed the rise of Homo erectus, the creators of the mysterious Acheulean hand axe and masters of reshaping large flakes of stone, as well as a parallel lineage of bipedal apes, the heavily built genus Paranthropus.

A stubborn tree on the sandy Pleistocene cliffs of Lobolo doing a decent impression of our messy family tree (or family bush).

The Paranthropus lineage took a different evolutionary track than Homo. The paranthropines were built for heavy lifting with their faces, sporting massive, Mohawk-like crests on their crania for attaching bulging chewing muscles and huge, nickle-sized molars for grinding up their food, earning them the nickname “nutcracker man.” But what exactly the massive paranthropines were eating is tough to sort out (pun intended) and there’s a lot of conflicting data to wade through. Tubers? Grasses? Termites? Whatever they wanted?

What we do know is the modern world is very weird in the course of human history because there is only one bipedal ape species running around…unless my uncle is a Neanderthal.

Cory, a lone bipedal ape, searching for evidence of our evolutionary cousins, the paranthropines, and our great-great-etc. grandparents.

In order to explore what Paranthropus might have been adapted for, we needed to take a closer look at chewing. Like, an uncomfortably close look. Dr. Matt Skinner had half the students volunteer to be our designated chewers. They were given different types of food then told to eat. While the snacks were distributed, the remaining students were instructed to watch the eaters munch, recording which teeth each chewer used to break into the food then which teeth they used to finish the job.

Primate behaviorists observe a strange troop of primates. (Left to right: Ana, Natalie, Meg, Marcel, Dr. Matt Skinner, and Dr. Meave Leakey observe while Leanna, John, Ingrid, Ashley, and Aaron get through their biscuits)

But Paranthropus and Homo erectus weren’t the only products of Pleistocene climatic chaos. While Homo erectus became the first hominin to hike out of Africa into Asia, in Africa the lineage continued to increase its cranial capacity and refine its toolkit. First evolving into Homo heidelbergensis, the shrinking teeth and sophisticated tools become signs of approaching modernity. When our faces have finally slid backwards in line with our foreheads and our chins emerge below our incisors, we have finally arrived at Homo sapiens, one of the more interesting products of the fickle Pleistocene.

Rosie and Bailie sketch the face of Homo helmei or the "Eliye Springs Skull." This specimen is the reason we set off for Lobolo, a site near Eliye Springs on the shores of Lake Turkana, for our final field excursion of the season.

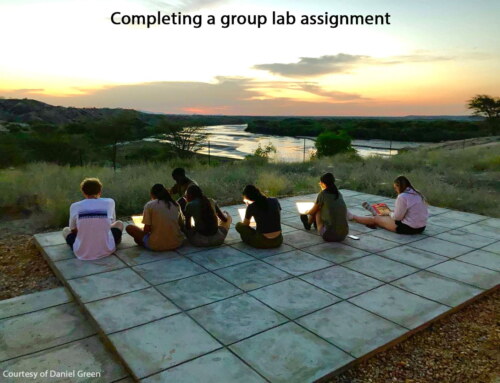

After hauling through the final stages of the human evolutionary story in the classroom, it was time to go on our final field trip and search for the fossils that tell this last piece of the story, when we go from being another bipedal ape to something we would call human. Our destination was Lobolo, a sandy set of steep cliffs along the shores of Lake Turkana near Eliye Springs, our favorite spot to take a dip in the lake.

Cory and Rob crossing the fickle Turkwel for the last field trip. This area may have been under flowing water two days ago, and now sits high and dry after the channel shifted to the north.

In 1983, two tourists showed up at the National Museum in Nairobi and plunked a skull down on Richard Leakey’s desk. He’d seen a lot of “fossils” that turned out to be modern goat and monkey fragments, but this skull had weird mix of features, some that looked like modern Homo sapiens – and others, like a pronounced brow ridge – that linked it to something more ancient such as Homo heidelbergensis. This was an important fossil for sorting out the origins of our species.

Natalie, Holly, and Francis look over the home of the Eliye Springs skull. Somewhere along this coastline is the rest of Homo helmei. Also along this coastline is a great place to set up a beach umbrella and enjoy a sundowner before the hippos emerge from the lake.

Dr. Leakey, unsure when to congratulate them on the discovery or scold them for illegally collecting a fossil, asked where they’d picked up the skull. They’d been vacationing on the shores of Lake Turkana and had gone for a walk near Eliye Springs. They agreed to accompany the Leakeys to the place. But they didn’t exactly remember where “the place” was. Combing the beach, they didn’t find the rest of the skull, but field crews have returned to the area over the years and found tantalizing hominin humeral fragments and Pleistocene fauna that keeps them coming back to continue the search for more of our direct Pleistocene ancestors.

The field crew and the field vehicle. An image that defines the end of a successful season. Top row: Aaron, Tim, Ashley, Holly, Rosie, Maegan, Eve, Natalie. Second row: Radames, John, Sam, Bailie, Rachel, Leanna, Ana, Rob, Dr. Matt Skinner, Cory, Meg, Ingrid. First row: Francis, Marcel, Francis, Dr. Meave Leakey, and Matt

The loose sand we would be prospecting was laid down at some point between 2.5 million years ago and 10,000 years ago and were full of fish material indicating the expansion of Lake Turkana and its shifting connections to the Indian Ocean and the Nile River through that time period. The outcrop was also a great place to take in a panoramic view of Lake Turkana and scramble over the cliffs and boulders that erode with every dramatic rainstorm. Along with the fish fossils, there were bits and pieces of hippo and crocodile and a few scraps of ruminant ungulates like antelope.

Maegan and Eve by a Pleistocene boulder after a warm morning picking through fish, hippo, and croc bones in search of our elusive ancestors and distant cousins.

After a few hours crawling the buttes in search of Ice Age hominids on a warm morning, the lake looked more and more inviting. With the area declared searched by Dr. Skinner and Dr. Leakey, we splashed in to rinse off the grit and close out the “field” part of the field school.

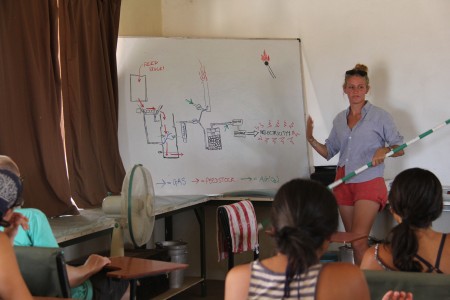

Back in camp, Acacia Leakey gave a brief lecture and tour of the renewable resource projects she has been working on during her year at TBI. Acacia is interested in studying engineering at university and her technical prowess was on full display as she described the inner workings of a prototype gasifier that she’s been building and trying to get up and running.

Acacia reveals the inner workings of the gasifier, a machine she has been maintaining which converts the ubiquitous doum palm nuts into organic gas and finally electricity.

Normally all the electricity in camp is provided by massive solar panels on the roof of the research building. But when we get a cloudy day, the batteries run low and the generators need to kick on. The gasifier would replace the generators, turning doum palm nuts, a favorite snack of Turkana kids and a favorite piece of sporting equipment for the field school students, into combustible energy that can run the generator without fossil fuels (a massive oversimplification. Sorry, Acacia). It sounds too good to be true, but other prototypes have been used to run cars and other research facilities around the world.

Acacia and her stubborn baby. The gasifier is on the verge of working. Just a few software kinks to work out, yet...

As if creating energy from palm nuts wasn’t enough, Acacia also has a project trying to maintain a sustainable aquaculture project. Her goal is to sustainably raise tilapia, wonder fish that can graze on algea and larvae, in a series of self-contained fishponds on the TBI campus. At the beginning of the term she was having some issues with insect predators and overpopulation keeping the fish at smaller sizes. Now she’s separated most of the males from the females so they’ve stopped breeding and started growing. We watched her excitedly fish out a filet-sized tilapia from one of her ponds. Her work will continue on both of these projects through the spring and summer before she heads to school to expand her engineering tool-kit.

Acacia leads a tour of the fishponds. As she discussed the increased proportions of the ponds after separating the males and females she threw in her trap and excitedly pulled out a large, healthy tilapia. This aquaculture-in-the-desert think could really happen.

After learning about how the doum palm nuts could be used to fuel TBI and watching the fish splash around in muddy water, we took the logical next step and geared up for Doumball, the sport taking the Turkwel by storm.

Cory, Acacia, Rosie were suiting up for Doumball by rolling in the mud when Ashley decided she needed to take a load off for a second on the team bench.

This would be it, the final slip and slide through the muck of the meandering Turkwel River, the glory and pride of the season the cherished trophy awarded to the winners of the Doumball World Series 2013 in Turkwel Park, Turkana, Kenya.

We don’t play with the same people or the same teams every time so there really wouldn’t be a defending championship team. Instead we sort separate the players through a rock-paper-scissors duel with me. With the championship teams settled, a fair split with the sluggers on opposite sides we set the bases facing the setting sun, crafted our final bat of the season, and threw the first pitch.

It was a tense game with double-plays, home-runs, close pickles, and closer slides that were called by our ump and scorekeeper Marcel (he says he’s an impartial judge because he’s Swiss). As the light faded and the river began to rise, the Osteoblast Ponies were down by 7. If we could bring our remaining batters home, we might be able to tie this thing up. Two outs, bases loaded, the sunset long ago faded to grey murk. The brown, fuzzy ball was impossible to see in the reddish-brown mud. A pop fly. A snag. And that was a ball game. The Turtles took home the 2013 crown.

Happiness is an evening spent splashing through the mud of the Turkwel with your closest new friends, a doum palm nut, and a few inner tubes. (Top: Francis, Meg, Sam, John, Ashley, Natalie, Leanna, Rob, Cory, Matt Skinner. Front: Bailie, Holly, Matt, Eve, Acacia, Ingrid, Tim, and Rosie.)

Another “final.” After our final trip to Lodwar, our final swim in Lake Turkana, our final field trip, our final soccer match, and our final doumball game, this “final” thing was becoming real. Ahead we had a few more finals. The final Paleoanthropology exam, the final student presentations, then graduation, and our final goodbye to TBI…