On Thursday, after having collected all the raw materials during the Nariokotome trip, it was time for our young hominins to test their knapping skills and prove their worth to the Oldowan community. But before we started, the students made a short trip just outside the compound to collect some quartz pebbles to use as smaller hammerstones and as raw material for the first phase of the experimental archaeology session.

Phase 1 – “Pebble Culture”

When the first early stone tools were discovered by Mary and Louis Leakey at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, the assemblage was characterized as a “pebble culture”, to which the term Oldowan was attributed to. This was because the tools found were made out of pebbles. Since this discovery, however, many other Oldowan sites have been found and we now know that there was a greater variety of raw materials used to produce these tools which was not only restricted to pebble forms. Nevertheless, the use of pebbles is a feature of several Oldowan sites, so it was time for our hominins to journey back to 2.6 – 1.8 million years ago and knap some oldowan tools out of the quartz pebbles they collected.

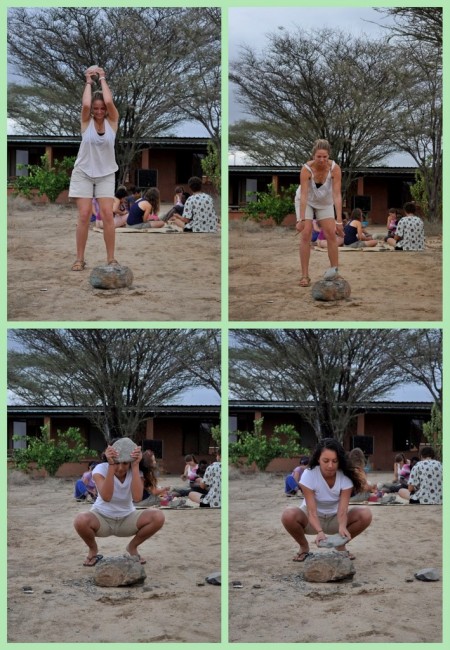

Quartz isn’t an easy material to fracture, especially when trying to remove flakes with a quartz hammerstone, so Dr. Sonia Harmand explained some knapping basics to help them on their way. At first there was a lot of chimp-like pounding, but as the students got the hang of the arm movement with some help from Dr. Harmand, flakes started flying everywhere, and slowly by slowly they began to transform their pebbles into the desired Oldowan tools – choppers and chopping tools.

From top left: Lauren, Robyn, Janina, Abdi and Kat; working on their quartz pebbles (Robyn and Kat are showing the chopping tools they made).

Phase 2 – Acheulean handaxes

With Phase 1 complete, our Oldowan hominins turned into Acheulean hominins (at 1.76 million years ago) as they tackled the big blocks of phonolite and rhyolite and attempted to make their very own handaxes – a typical tool from this period. In order to produce a handaxe, a very important part of the process is the selection of the right raw material. First and foremost, it should be a material that flakes cleanly and predictably, but the chosen blank also needs to be more or less flat and thin, possess “good angles” (smaller than 90º), and ideally already have an almond shape akin to that of the desired product.

Knapping phonolite with basalt hammerstones is much easier than quartz on quartz because there is a significant difference in rock hardness between phonolite and basalt, with basalt being the hardest. But the trick here was to be able to plan each move carefully so as to remove long, thin flakes on both sides of the blank and, at the same time, have in mind the symmetry and shape of the final product.

The hardest bit of all was to not snap the tip off the handaxe with a misplaced strike. The sad look on the students faces when this happened was heartbreaking, especially when they were so close to completion, but they never gave up and by the end of the day several handaxes had been made by our now Acheulean community.

Not all our young hominins were successful in the handaxe challenge, but they demonstrated their skill by removing thin and sharp flakes from their phonolite and rhyolite cores, which they then retouched, using smaller pebble hammerstones, into beautiful tools which were ideal for the last phase of the experiment – butchering the goat.

Some of the tools produced by the students. The top two rows are handaxes, and on the last row we have a rhyolite chopping tool, a phonolite retouched flake, a quartz chopping tool, and a retouched rhyolite “flake-blade”.

Phase 3 – Goat Butchery

Now with the freshly made tools, the students headed to the staff kitchen to test them on a goat carcass that was to be their dinner. The goat had been slaughtered earlier with a modern knife and was laid on a bed of Esekon leaves which have antibacterial properties.

After Francis inspected and approved all the stone tools the students had brought, he and Isaiah showed them where to start.

As is Turkana tradition, Francis laid out the intestines and read the weather forecast from them, indicating what each vein, bump and squiggle meant. “Here you see many rivers,” he said, “it is going to rain in the next few days”. And it did!

Through experimental archaeology the students were able to better understand the mechanical and cognitive aspects of stone tool production as well as the importance and use of such tools to our ancestors.

The assemblage of cores, flakes, hammerstones and finished tools left behind after the students finished.

In the evening, the goat was roasted and the students had a banquet of goat, ugali (a maize flour dish), rice, sukuma wiki (a dish made of kale and tomato), a tomato and onion salad, and cake! A perfect end to a day in the life of an early hominin.

Next up: Human Evolution!