Last Spring semester Dr. Fortelius, Dr. Meave Leakey and the TBI students initiated a simple taphonomy experiment. They started off with the exciting task of smashing Mary Leakey’s crockery into small pieces, which were then buried at different levels within the TBI compound. Here is the link to the blog post: https://www.turkanabasin.org/2013/03/paleontology-off-to-a-smashing-start/.

Taphonomy is the study of the processes and environmental forces that act upon organisms after death, in the lead-up to fossilization. Using the broken crockery sherds as a model, the aim of this exercise is twofold – to assess and better understand the taphonomic processes that occur over time on a given organism; and to get a grasp on how different organisms are classified based on the remains that are found.

This Spring semester, the task for the TBI students was to look for the sherds deposited by the previous field school and collect them for a taphonomical and cladistic analysis. In a nutshell, cladistics is a method of assessing the evolutionary history and relatedness of different groups of organisms based on the number of shared and derived characteristics they have.

But first, a bit of excavation practice…

Before heading out to the crockery site, Kat briefly explained the various steps leading up to the excavation of a site and instructed the students on how to set up 1×1 metre test pits. For this you need: string, nails, measuring tapes and a compass/GPS. The students were quick learners and they got their 3 squares set up in no time! It was now time to head to the crockery site and look for evidence of our ceramic organisms.

First the students set out a baseline aligned North-South to orientate their excavation grid; and then using what they learned in the practice session they set out 1×1 metre squares in strategic areas and began their mini-excavation.

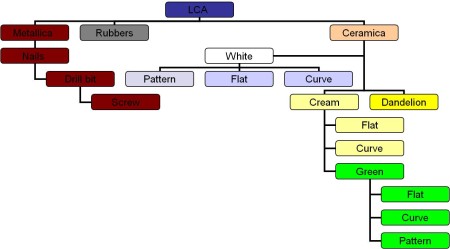

After the excavation, the students took the finds they collected to the classroom where they started to make their analysis – first by grouping the different pieces into categories (or species) and then by constructing a cladogram linking all the species together. During the excavation the students also found unexpected species – metals and rubbers – which they decided to also include in their study. But where would they place? There was crockery with some metallic decoration… So would this be considered a primitive characteristic inherited from a common ancestor or a result of convergent evolution?

As the students discussed the possible evolutionary relationships between the various species they identified, they realized how difficult it can be to group specimens together when they are all fragmented and many pieces are missing; and also how there are many different cladograms that can result from such a varied assemblage of fragments. Which one is right? And how many species are there?

And this is the great conundrum that is still with us today – not just with the simple modelling with crockery fragments, but, more importantly, with the identification and reconstruction of evolutionary relationships between different animal and hominin species found in the fossil record.

As the Vertebrate Palaeontology module drew to an end, the students reburied the items they found, so the experiment could carry on through the many field schools to come. Keep an eye out for future developments on this next semester!