We safely arrived at Ileret, excited to start the second half of the ecology module (don’t worry, the rest of the students made it too).

Kenya contains a wide variety of environments and habitats within its boundaries. At Mpala, we observed savannah and woodland environments that were very green following good amounts of rainfall. We are not in Mpala anymore! Students observed the stark differences between the vegetation in the semi-desert surrounding TBI Ileret and that of Mpala in Laikipia. Even the acacia trees have different shapes. The canopies have wide, flat tops and they slowly decrease in width towards the base, providing as much shade for the roots as possible to prevent evaporation.

The semi-desert landscape around Ileret. The green belt of vegetation pictured here indicates a dried, seasonal riverbed. these riverbeds flood on occasion, as the water table underneath them is high.

Jen and Kait find a special bond in the desert.

Maddie enjoys the view at Sibiloi National Park, near TBI Ileret.

Yemane takes in his new surroundings.

Different plants have different ways that they create energy from the sun (photosynthesis). Some have green leaves that generate sugars and starches from sun energy, others take their time growing, and have specialized cells in their bark (and a lot of thorns) to do the work.

We set out to explore this new environment at Sibiloi National Park. With far less annual rainfall, the vegetation in this area is all specially adapted to surviving with little water, retaining whatever it can, and having fairly dramatic methods of protection (such as thorns, spines, or toxins). Luckily for us, several different plant species were flowering, and we observed all sorts of different pollinators visiting the blooms. It was particularly rewarding to visit this park with Dr. Dino J. Martins, a leading expert in the field of entomology and biodiversity.

The desert rose flower. A stunningly beautiful pop of color in this desert landscape.

The brown veined butterfly continued its migration – we had been studying them at Mpala – and were aiding in pollination all over the landscape.

The milkweed plants showed us their beautiful colors.

Some of these plants are highly specialized to this environment. Such as the desert rose – a plant firmly rooted in the rocky ground. It grows incredibly slowly, conserving energy. We estimated the age of a particularly large desert rose tree. Turns out it is likely about 1000 years old!

Rob checks out the sturdy, waxy bark of the desert rose tree.

Milena contemplates the age of this large desert rose tree.

Niguss gets a closer look at the specialized leaves on the desert rose tree.

Joe and Kait collect photos and samples of the desert rose.

The roots of the large desert rose tree have anchored this plant solidly among the rocks for over a thousand years.

Ryan finds some shade in the large desert rose tree.

TBI students give their best guesses for the age of the tree.

Students discovered ancient Nile oyster beds among the rocks during our Sibiloi park hike. This area was once underwater!

Adriadne passes an ancient oyster shell to her peers.

Kaitlin gives us an up-close view of the ancient Nile oysters.

Students found some other skeletons along the way. Evan found the skull of a goat!

Indigofera spinosa is a spiny plant that can survive in extremely hot and dry environments. It is abundant in this semi-desert environment, providing a food source for livestock. These plants are some of the most abundant in the areas around Ileret. Because they are a main food source for livestock, they are perfect subjects for studies human impact on vegetation by pastoralism.

Students check out the small indigofera spinosa plants. These have been munched down by local livestock of the seasons – they can grow much taller.

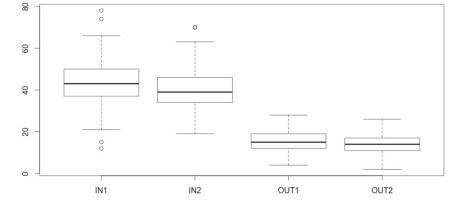

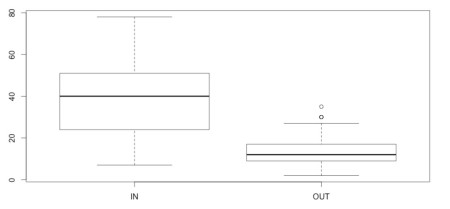

TBI students in 2015 began collecting data on the heights of Indigofera spinosa plants located inside the TBI Ileret compound (a fenced area without grazing animals) and outside of the fence (areas frequently grazed by livestock). Students replicated this study this semester, collecting another dataset. It turns out that a significant pattern is emerging – showing differences in the sizes of Indigofera spinosa plants in areas with and without grazing.

2015 measurements of indigofera spins plants inside and outside the fence surrounding TBI Ileret.

Current measurements of indigofera spins plants inside and outside the fence surrounding TBI Ileret, collected but TBI students last week.

Data like these are essential to understanding human impact on the environment – a highly relevant issue for a sensitive arid environment and pastoralist communities who so heavily depend on its stability. Does grazing help control the coverage of indigofera spinosa, thus making way for a larger diversity of plants to co-exist? Or does grazing effectively spread indigofera spinosa plant seeds, encouraging more growth in previously grazed areas? How much grazing is too much? If the plants are grazed too heavily, will the soil underneath them recover and host other plant life? These are all important questions that can be answered with the methodologies that we have learned over the past few weeks in vegetation ecology.

After completing this lab exercise, the students and I went to visit some of the local pastoralist families that live close to the TBI compound. These types of experiences are important for us to understand a little bit about the life of pastoralist peoples in this arid environment. The biggest cultural group that surrounds TBI Ileret is the Dassenitch. The main livelihood of the Dassenitch is pastoralism. We visited two nomadic homesteads that house both people and livestock – called bomas.

The Dassenitch create places to keep livestock by collecting thorny branches of the acacia trees and building fences. These keep the livestock in, and wildcats, hyenas or even leopards out.

Smaller fenced areas are sometimes created for juvenile livestock

The Dassenitch create living structures out of local plant materials and odds and ends (plastics and cloth). These are temporary places to live, as they move around the landscape according to wet and dry seasons. You don’t need much when you’re moving around often.

The women of a Dassenitch family and their children. They were so kind to let us visit their home.

A head of the boma shows us where he keeps his livestock.

Yemane can’t resist a chance to hold the baby boy.

Tadele meets the newest member of the family.

Ryan, Kait and Adriadne gather around a new member of the livestock family – a baby sheep!

The baby sheep is pretty comfortable with Milena, and that makes her happy.

Jen and Adriadne get a chance to hold the baby sheep.

Students vs. livestock. Who will win? Next week, they will learn how to reverse engineer their diet through analysis of dung and teeth!

The bomas around TBI Ileret also keep donkeys – they are mostly used for transporting belongings long distances.

Pastoralists such as the Dassenitch have to regulate when juvenile animals can nurse, because they also need to collect the animals’ milk for food.

A Dassenitch women shows us how she milks the cows.

On our visit we spoke with families who kept several different types of livestock: sheep, goat, donkeys, and cattle. These bomas are simple structures made mostly of natural, local materials (such as branches), as well as some other commercial materials (plastic, corrugated tin, etc.). The simplicity of these structures is intentional, as these pastoralists move around the landscape often, according to changes in the rainy and dry seasons. There is no sense in building a brick and mortar home, only to leave it three months later. Life for the Dassenitch depends on the health of livestock, which is related to the seasons and the health of surrounding vegetation.

We ended our ecology module with lessons about freshwater ecology. Lake Turkana is a slightly Alkaline lake (but its safe to swim in).

A view of the shoreline. Note the tall reeds that provide a home for fish…and sometimes crocodiles (not at this beach though!).

There are all kinds of species that have evolved around the lake. In class we discussed some of the implications about declining lake levels due to dams for irrigation in the Omo river (in Ethiopia) and climate change. What will happen to the environment and communities of people surrounding the lake? There is no straight-forward answer. We do know that human activities and declining lake levels are impacting keystone species. A keystone animal is a species that contributes more than its own body mass to an environment. For example, hippos feed on vegetation around the lake margins and their dung adds nutrients to the system. This keeps some vegetation in check, while ensuring there are enough nutrients for more vegetation to grow. All sorts of aquatic organisms feed on this vegetation, moving all the way up the food chain. So, changes in hippo populations can have drastic impacts on the entire ecosystem. Hippos and Nile crocodiles are keystone species for the Lake Turkana.

The health of the Lake Turkana ecosystem is of dire importance to its surrounding animal and human communities. Fishing contributes a huge proportion of the economy surrounding Lake Turkana. Fisheries operate on local and global commercial scales. Fish, such as Nile Perch and Tilapia, are dried and smoked and sent all over Kenya and other countries in Africa. Some of this fish is even sent across continents to Europe and North America. Check the prices of Nile Perch (if you can find it) back home – it’s pricey stuff when it’s exported internationally. The TBI students often have the treat of these fresh fish for dinner at least once or twice a week – we are spoiled!

A sound scientific understanding of the ecology of Lake Turkana and its surrounding areas is pertinent to the health of wildlife, but also of the economy. Future generations of scientists need to investigate the impacts of human activities (dams, irrigation, agricultural and human waste, etc.), climate change, and declining lake levels on Lake Turkana ecological systems. Maybe some of our students will have the opportunity to do such science.

But in the meantime, the students enjoyed a refreshing swim in the lake.

Walking out into the water. You can walk out really far – it’s a fairly shallow lake. The deepest point of the lake is only around 90 meters deep. The average depth is only around 5 meters.

The students come back to shore – careful for the rocks!

Stay tuned for an update on our next module…Paleontology!