We know that the Earth is between 4-5 billion years old. Its vast life history recorded in the ground. Paleontologists use evidence of past life on Earth from fossils (of plants and animals) to understand the many changes in climates and environments that took place.

Professor Mikael Fortelius arrived, and we began our lessons in Paleontology. Prof. Fortelius specializes in mammalian communities in early human environments, evolution of land mammals and their environments during the late Cenozoic, ecometrics of fossil and living mammals, computation approaches to paleobiology, all things about mammalian teeth and issues with scaling. It is an incredible opportunity for TBI students to learn from a leader in this field.

The students were very eager to get out into the field to search for fossils – but first they had to assess their skills in fossil identification. We placed a random assortment of fossils (and non-fossils!) into trays and asked students to do their best at describing and identifying them. They learned from each other in groups and excelled at the assignment.

The students formed groups and provided their best descriptions and identifications of the random items.

Some students’ experiences with bones came in handy, and they shared their prior knowledge with peers.

Prof. Fortelius revealed the correct answers of the fossil identifications at the end of the task.

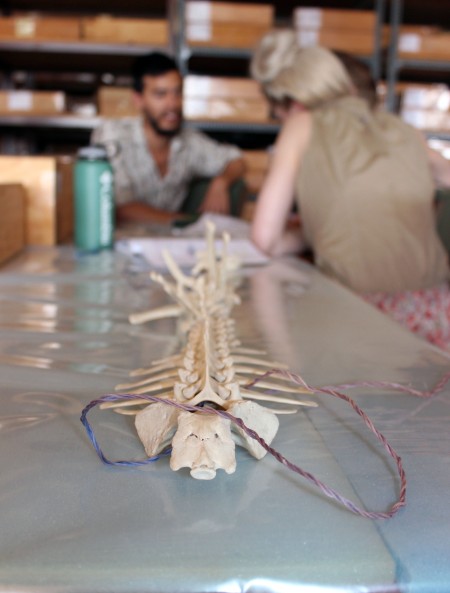

Following this initial attempt at fossil identification, and realizing there is a lot to learn, the TBI students had the opportunity to learn vertebrate anatomy hands-on. Prof. Fortelius and his fossil expert assistant, Martin, laid out the full skeletons of many different modern species of vertebrates. The students were able to lay out the skeletons to see their anatomy, compare features of different species, and get an overall stronger feel for the many shapes and sizes of bones. Seeing complete modern skeletons makes identifying very old, fragmented fossil bones a bit easier in the field. Everything that we know about the fossils of extinct animals is based on what we can learn from the modern record. This is why is it important to understand both the past and the present in understanding the evolution of life on Earth.

TBI students gathered around tables with modern animal skeletons, working together to understand how the bones come together.

Complete spines of various animal species were available to students for comparison.

The students were able to look at and handle skeletons of all shapes and sizes. Kait, Jen and Ryan check out a tiny bush baby skeleton.

Ryan examines the similarities and differences between pelvises of different species.

Prof. Fortelius helps Niguss examine the skeleton of a modern horse.

Prof. Fortelius and Martin discuss the correct articulation of a cow skull and mandible with Kait and Jen.

Martin shows images of fully fleshed animals to Tadele to help him visualize the skeleton on the table.

Max, Jamie and Rob check out some carnivore skulls.

Joe

Evan, Rob, Kait and Jen investigate the skeleton of a warthog.

You can tell a lot about animals’ lives by looking at their teeth. A huge body of research investigates the mechanics of jaws and teeth, and the impact on these mechanics and different food items on tooth wear. Studies of modern animal teeth and jaws helps inform about wear patterns on fossils. We can then reconstruct the diets of ancient animals who have long been extinct.

Beyond wear, the mechanics of different shapes and sizes of jaw and teeth structures indicate adaptations for different diets. For example, browsers (who eat the vegetation on bushes, shrubs and trees) have sharper teeth with more shearing crests than grazers (animals who eat grasses) that have flatter, rounder teeth for repetitive wearing down of tough plant materials. So, you can use the shapes of animal teeth to tell what they probably ate. The students looked first-hand at different jaws and teeth from different herbivores to tell the difference between browsers and grazers.

Zebra mandible (left) and skull (right).

Black rhino skull.

Prof. Fortelius discusses the anatomical differences in teeth and jaws between grazers and browsers.

Kudu skull.

After the students became familiar with vertebrate anatomy and fossils, it was time to take them out to the field to search for fossils. We took a half-day trip to Area 8 (about 30min from TBI Ileret), which is an area rich in fossil remains. The students scoured the surface of this area for fossils, finding the remains of hippo, elephant, crocodiles, and more. The most important part of this field excursion was learning the standardized protocol for recording fossil finds (initiated and designed by Meave Leakey and others).

Yemane and Evan record a fragment of horn core using a standardized protocol.

Niguss found a hippo tooth!

Niguss, Tadele and Yemane discuss a fossil find.

Joe and Jamie confirm with Prof. Fortelius about the depositional context of their fossil find.

Max found a crocodile tooth!

Martin instructs Jen and Milena how to systematically record a fossil find.

Jen and Maddie practice their fossil finding and recording skills.

At the end of our field adventure, we visited an excavation site from a few years ago where researchers found fossil hominin teeth.

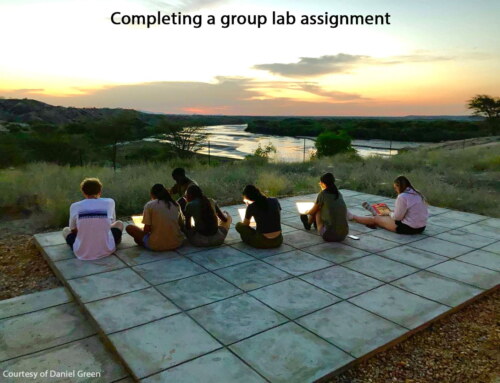

Students rounded off the end of Paleontology week 1 with a lecture on the history of life on Earth. The students took part in a fun activity to understand just how vast the timespan of Earth’s history extends – the toilet paper timeline! Students were given a few rolls of toilet paper, masking tape and some markers. Two groups were asked to roll out the toilet paper and map out, to scale, the age of the Earth. Then, students were asked to mark on the toilet paper when certain events in Earth’s history, such as snowball earth, occurred. FYI: it takes a lot of toilet paper to complete the task.

Yemane, Maddie, Joe and Adriadne mark out the history of Earth making sure they divide the time equally into each toilet paper square.

Jamie fixes the toilet paper to the floor as Jen marks out even intervals of time.

Prof. Fortelius watches the students complete the toilet paper timeline with amusement.

Stay tuned for more on Paleontology next week….