We switched our focus in the Archaeology module back to the Stone Age, starting with some hands-on learning about ancient stone tool technology. Understanding stone tools by simply observing archaeological artifacts is a tricky thing – even seeing that these objects are artifacts can be challenging if you don’t have years of experience. Many archaeologists have found that the quickest way to understand stone tools is to learn how to make and use them.

Prof. Hildebrand, TA Hilary Duke and TBI research assistant John Ekusi took the students to a stand of palm trees just off campus to learn how to process palm nuts using stone tools. Even though stone tools can be made very sharp, not all stone tools are made for the purpose of cutting things like meat. Stone tools can be used in other activities such as cracking open nuts, pounding tough fibrous plant materials, or even smashing open bones to get access to marrow. These percussive activities were likely important parts of early hominin life.

John Ekusi is a TBI research assistant who grew up in the Nariokotome region of Turkana. He is an expert in processing palm nuts for eating. John kindly showed the students how to process these nuts using stone.

John Ekusi explains the whole nut collecting and processing procedure before the students practice.

The first step in processing palm nuts is to collect them – but they are sitting high up in the trees. The students (and instructors) did their best to knock down some nuts by throwing stones.

Evan collecting palm nuts.

Hilary takes her best shot.

Prof. Hildebrand throws a stone up into the trees in hopes of shaking loose some palm nuts.

Yemen throws a stone into the tree-tops.

Rob takes his best shot.

Maddie throws a stone to make palm nuts fall from the trees.

Field School director Linda Martin uses her good throwin’ arm.

Jen gets some serious height, throwing her stone high into the nut clusters in the tree.

Jamie takes aim…

Next, the students had to select their stone tools for processing the nuts. The nuts have a tough, fibrous outer coating that must be removed to get to the sweet edible flesh underneath. The most effective way to do this is to grind off the outer layer by placing the nut on a solid and stable stone (an anvil stone) and using a rough, rounded stone in your hand to do the abrading. John Ekusi demonstrated this process for the students before they gave it a try.

John Ekusi demonstrates the palm nut processing.

Students carefully observe John and pick up the skills quickly.

Evan, Maddie, Jamie, Jen and Ryan work on removing the outer layer of their palm nuts.

Adriadne and Milena get used to their new toolkits.

Yemen finds a comfortable posture to work on the palm nut.

Ryan carefully removes the outer layer of the palm nut.

Rob works on getting his palm nut ready for eating.

Niguss gets into a good rhythm.

Milena works on removing all of the outer layer of the nut.

Max is getting the hang of this!

Joe works carefully on removing the outer layer without damaging the edible palm nut flesh.

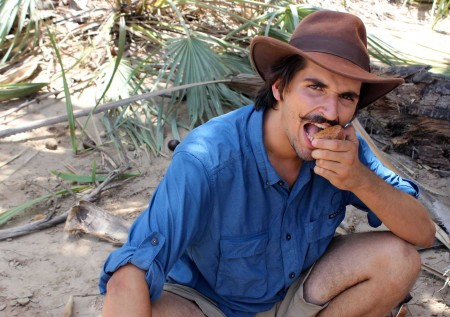

After removing the outer layer, some students tasted the palm nuts – they were a hit!

Jen enjoys some palm nut goodness.

Evan takes a bite!

After having used stones to process the palm nuts, students had a better understanding of past hominin activities using stone tools. Next up – learning how to make the stone tools sharp for cutting.

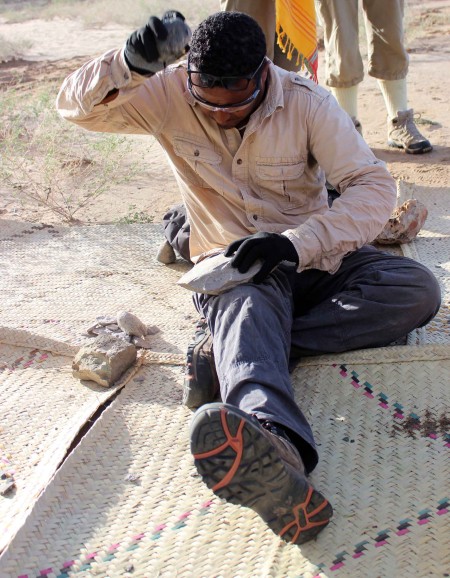

Hilary distributed the tools required to do some basic stone tool-making. The students used stone hammers to hit cobbles of phonolite (a good volcanic toolstone that was used often by hominins throughout prehistory in this region) and remove sharp pieces called ‘flakes’. Hilary instructed the students how to find good angles on their cobbles to hit and successfully remove flakes. It is best to find an acute angle (less than 90 degrees) between two surfaces on the cobbles. Hitting this acute edge will ensure that the blow is more likely to remove a flake in a controlled manner. With only a few instructions, the students practiced on their own, finding their own nuanced techniques and picking up the skills quickly.

TBI students gather around as TA Hilary Duke provides some basic stone tool-making instructions.

Hilary demonstrates an example of correct postures for making stone tools.

Professor Hildebrand joins the group for some tool-making!

Evan is soon a tool-making pro.

Adrian stands proud with the first flake that she made.

Tadele works hard at breaking apart this tough phonolite cobble – this material is no joke!

Tadele fits the flakes back onto the cobble to get a better understanding of his sequence of hits.

The students work hard at practicing their tool-making skills.

Niguss works at making lots of flakes – a natural!

Max and his first flake!

Making stone tools can be hilarious too…

Joe concentrates on hitting the cobble at the right angle to break off a flake.

Jen finds a comfortable position to work on getting some flakes from this nice acute angle.

Jamie takes a turn at making flakes….

…and it was a success!

Armed with their newfound skills in making and using stone tools, the students were ready to take a closer look at some archaeological collections. The students got a close-up look at one of the most important finds from this area of the world. A few years ago, Drs. Sonia Harmand and Jason Lewis (now at Stony Brook University) and the West Turkana Archaeological Project (WTAP) discovered the oldest stone tools in the world at a site called Lomekwi 3. Dating to 3.3 million years ago, these tools push back hominin stone tool-making over 1 million years earlier than was previously known. Not only does this discovery stretch hominin stone tool-making deeper into evolutionary history, the tools also shed new light on the variability within stone tool-making and using behaviors. Previously, the world’s oldest stone tools were thought to be in Ethiopia dating to 2.6 million years ago. These tools showed evidence of hominins creating flakes (much like how the TBI students learned in this module). The Lomekwi 3 tools, however, look much different and indicate hominins were engaging in other percussive activities with stone.

As a member of the WTAP, TA Hilary Duke lead a lab session for the students so that they could observe these tools and gain an understanding of the world’s oldest known stone tool technology.

Hilary guides the students through the process of looking at the tools and understanding how they were used or made.

Understanding how early hominins made stone tools and knowing what they used them for is an incredibly challenging process. The TBI students took some important first steps in hands-on learning to gain a better perspective on these early technologies. Next, the students will learn important archaeological survey skills as they visit sites that range in dates from the Early Pleistocene to the mid-Holocene.

Stay tuned for more about the students’ trip to Nariokotome and the important archaeological sites that they visited…