The Early Pleistocene archaeological sites on the west side of Late Turkana are some of the richest areas for early hominin behavioral research in the world. Dozens of sites provide large quantities of stone tools made on a range of different raw materials. Intensive archaeologists studies in this area attempt to reconstruct hominin movements and use of local resources in these areas. During this time, around 2 million years ago, a lot of things started to change. New hominin species emerged (such as Homo erectus), some environments in eastern Africa became drier and more open, and hominins began to make new stone tools in new ways.

The students enjoyed a whirlwind tour of archaeological and paleoanthropological sites around the Nariokotome region during our final overnight trip. It took us about 6 hours in the TBI lorry to finally make it up north – and it was well worth the drive! En route to our camp at Nariokotome, we stopped at the Lokalalei Early Pleistcoene sites(~2.3 million years old) to practice some archaeological survey skills. Before the discovery at Lomekwi, the Lokalalei sites were some of only a handful of the world’s oldest archaeological sites. These sites are rich with material, boasting thousands of stone tools. Archaeologists have even been able to refit some of these tools back together to reconstruct how they were made by hominins over 2 million years ago! Through intensive studies of these tools, the data suggest that hominins had fairly advanced skills in tool-making (perhaps even better than some of our new TBI knapping novices) even during this early time. Hominins selected the best raw materials for the job and produced the tools using an organized and well thought out approach. The students performed a surface survey to locate stone tools that have recently eroded out of the archaeological site. These sites are so rich that even after over a decade of research new stone tools can still be found there.

The students form a line to perform a systematic survey for stone tools on the surface of a site at Lokalalei.

Professor Hildebrand assists Maddie in identifying stone tools.

Milena searches for stone tools at Lokalalei.

Joe places flags in the spots where he finds stone tools. These flags help us visualize the spatial extent of the archaeological surface finds.

Yemane gets a closer look to distinguish naturally broken rocks from stone tools – a challenging task!

Rob gets higher up in the section to see how far up the artifacts are located.

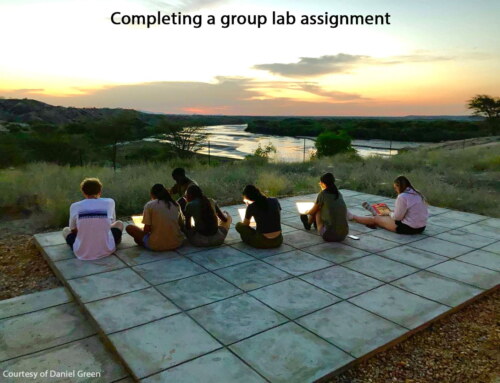

We enjoyed the gorgeous sunset after a long journey to the camp at Nariokotome.

The next day we toured more Early Plesitocene sites and started with a visit to the site where the fossil “Nariokotome Boy” was found. “Nariokotome Boy” (KNM-WT 15000) is a nearly complete skeleton of a juvenile male Homo erectus. At the time of it’s disovery, this specimen was the first nearly complete Homo erectus fossil, including many post-cranial elements crucial to reconstructions of how these animals moved around. The nearly complete skeleton of a juvenile individual also contains information about development and growth patterns in the Homo erectus species. This discovery proved how Homo erectus was the first known species in the hominin lineage to have a larger body frame, standing taller than ever before when upright. The pelvis and spinal structure of this creature had evolved to move very efficiently on two legs – an adaptation very pertinent to the later evolution of Homo sapiens. Luckily for us, TBI teaching staff Francis Ekai was personally present during the discovery of this fossil and witnessed its excavation first hand as a young boy. Both Francis and John Ekusi shared with the students their detailed knowledge about the discovery, excavation, and cultural heritage preservation of the site. Some archaeologists have theorized that changes in stone tool technology might be related to the emergence of this new species, indicating major evolutionary changes in hominin behavior.

Francis Ekai discusses the disvovery of ‘Nariokotome Boy’ and his personal experiences watching the excavation as a young boy.

Francis and John show the students the original excavation area where the fossil was found.

A monument marks this historic and important paleoanthropological find.

The monument is complete with a metal cast of the skeleton in its original position when it was found.

Following the “Nariokotome Boy” monument visit, we visited some of the richest Early Pleistocene archaeological sites in the world. These sites are located in a region called Kokiselei and range in dates from 1.8 to 1.7 million years ago. While we can’t ever pin down exactly which species of hominin made which specific stone tools, these tools were created just after the appearance of Homo erectus in this region. This suggests the possibility that some changes in stone tool technology may be associated with the appearance of this new hominin.

TA Hilary Duke is completing her dissertation research investigating stone tool technology from these sites at Kokiselei. She is attempting to answer what new technological behaviors emerged within these sites and how it happened. The students took a tour of these sites, looking at examples of these artifacts first hand in some more survey exercises.

TA Hilary Duke gives the TBI students a tour of the Kokiselei sites, explaining the archaeological context in which the artifacts were found.

We looked at some examples of artifacts found on the surface to explore their different shapes.

Hilary gives a hands-on tutorial for identifying different tool making strategies by observing features on stone tools.

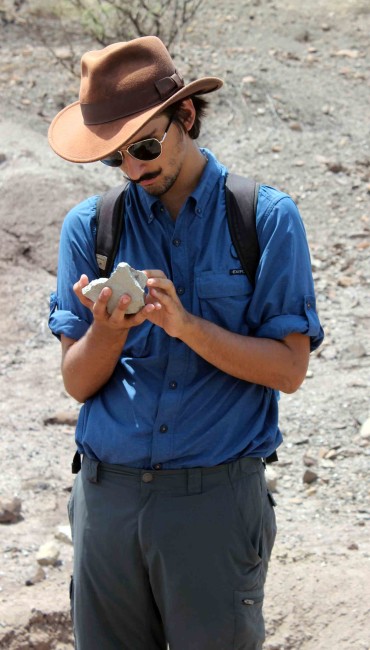

Evan takes a closer look at a tool from Kokiselei.

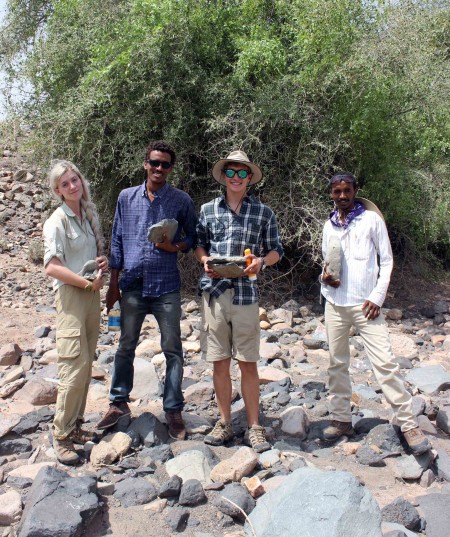

Students took a trip to a nearby riverbed to practice looking for the types of rocks hominin used to make tools at Kokiselei.

Students take a well deserved break in the shade for a picnic lunch in the Kokiselei riverbed.

We jumped forward in time to the Holocene and Prof. Hildebrand used her expertise to give the students a tour of some important sites. The first stop was a visit to what is colloquially known as the “Lothagam Harpoon” site. The name comes from the fact that many bone harpoon point artifacts have been found in this location. These harpoon points indicate a robust fishing lifestyle, in combination with other resource use strategies. This place is now situated in between the dual ridge system at Lothagam. The site dates to the mid-Holocene and is a place where hunter-gatherer-fisher peoples lived. The levels of Lake Turkana were much higher than they are today back then, and the area was wetter overall. This area was very rich in many difference resources, supporting the livelihoods of these people.

The students took part in a very important exercise, collecting spatial data points using GPS to demarcate the extent of the archaeological deposits. We know from excavations at this site in the past that the archaeological deposits occur in the white colored sediments. Thus, to find the potential extent of the archaeological site, we have to know the spatial extent of those sediments. The students split into teams to walk the edges of these deposits and record their spatial extent. It was a great opportunity for students to learn some of the mapping skills that they developed during the Geology module!

A view of the beautiful Lothagam ridge system.

Students hiking to the Lothagam Harpoon Site.

The white colored deposits that contain archaeological remains at the Lothagam Harpoon site.

Prof. Hildebrand discusses the context of the Lothagam Harpoon site.

The students reach the edges of the white sediment deposits, creating a map and drawing sections of the different geological layers.

Evan and Ryan measuring the section.

Jen carefully records information for the map of the Lothagam Harpoon site.

The mid-Holocene is a culturally exciting time according to the archaeological record which shows the emergence of monumental constructions using stone. People in this area of the Turkana Basin started to build massive structures out of stone, probably for some sort of communal and possibly ceremonial purpose. These structures usually take the form of what we call “pillar sites”. Pillar sites consist of massive pieces of columnar basalt arranged in some spatial orientation, and erected within large stone pavements. People would have collected tonnes and tonnes of rock material to create these structures and it would have been a massive effort by large groups of people. Some of these pillar sites serve as burial grounds.

The students visited a pillar site at Kalokol and Prof. Hildebrand discussed its construction and the archaeological data found there. According to Prof. Hildebrand’s research (as director of the Later Prehistory of West Turkana project), it is possible that new groups of people entered the Turkana Basin during the mid-Holocene, bringing with them this practice of constructing large-scale monuments. It is possible that these people may have also brought with them a new way of life – pastoralism. The construction of the pillar sites mostly alines with the timing of evidence for herding practices in the region (the most common way of life in the region even still today). The social and cultural implications of these newcomers meeting local groups are fascinating and complicated. We have only scratched the surface of beginning to understand it, and Prof. Hildebrand and the LPWT team continue to piece the evidence together to tell the story.

The pillar site at Kalokol. Note the large columns of basalt stone. They are standing upright within a platform made of hundreds of thousands of small pebbles and cobbles collected and carried by hand in the site’s construction.

Prof. Hildebrand discusses the construction of the site as well as the archaeological finds there.

Francis Ekai acts out local Turkana story about the stone pillars.

As the archaeology module came to a close, we finally had the opportunity to spend two days digging. Even during that short time, the TBI students learned several excavation skills. The students had the privilege to take part in opening a brand new archaeological site that Prof. Hildebrand and Field School Director Linda Martin recently discovered during survey. Prof. Hildebrand and Linda Martin surveyed areas near TBI Turkwel in search of archaeological sites that likely date to the mid-Holocene and therefore may represent people similar to those groups that built the pillar sites. While we have found the pillar sites and have excavated them, we have very little information about the everyday lives of the people that built them. Pieces of pottery and stone tools littered the surface of the site, pointing to the possibility that there may be many artifacts buried beneath the surface. Prof. Hildebrand and TA Hilary Duke laid out a grid over the site and selected several areas for test excavation squares.

The students were divided into several teams and began with recording what artifacts were on the surface of the ground within each square. After that, the students began digging! A scientific archaeological excavation moves very slowly so that every artifact and change in sediments must be recorded in detail. By moving slowly and recording the sediments, archaeologists can understand the depositional environment in which the artifacts are found. Without such contextual information, we would have no idea how the sites were formed and ultimately would not be able to reconstruct what activities took place at the site. The students practiced their careful excavation and recording skills and did an excellent job in recording the first finds from this new site.

Evan, Rob, Adriadne and Kait carefully brushed off the surface of the ground after they recorded and collected any surface finds.

Excavation can be very satisfying – it certainly was for Maddie!

John assists with the excavation of Joe, Milena and Niguss’ square.

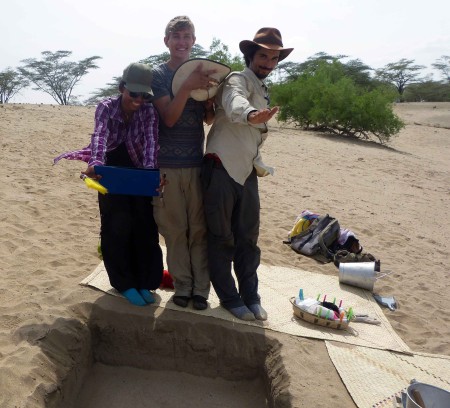

Prof. Hildebrand demonstrates how to dig straight walls in an excavation square. This is important to be able to read the different depositional environments as you dig down through the layers.

Joe, Niguss and Milena carefully look through the screen to find small fragments of artifacts that were dug up from the square.

Jen and Tadele carefully brush off the surface of their excavation square.

Francis demonstrates his excavation skills to Ryan and Yemane

Francis and John watch over yemane carefully as he places flags on several pieces of a broken pot.

Adriadne practices her skills for digging with straight walls.

Ryan learns how to use the total station. This machine can record the precise location of each artifact find – it’s very useful for constructing a precise map of the site later on.

Yemane holds the stadia rod for the total station. The rod is placed in the location of an artifact and serves as the target for the total station to record.

Rob attempts to hold the stadia rod perfectly level and still.

Prof. Hildebrand teaches John Ekusi how to run the total station machine.

We take photos of each archaeological layer during excavation, and sometimes you need the whole square to be shaded to get the correct coloring in the photo. Thanks for the shade guys!

At the end of the excavation we had to fill in the holes we dug to protect the preservation of the site. We placed yellow plastic tarp at the bottom of the excavation square before filling it with sediment to be sure we will know the boundary between natural sediment and what was excavated when the dig resumes next time.

Happy team after a good day of excavation.

The whole team after a very productive and successful two days of the dig.

What a fabulous Archaeology module! Next up….graduation!