On Monday and Tuesday, we had the opportunity to learn from Mpala researcher Kimani Ndung’u who specializes in vegetation studies and is currently investigating the effects of termite mounds on the locale-specific environment. He is also a part of a project (www.forestgeo.si.edu/site/mpala) run by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute where they are collecting data for the only savannah plot in their global network.

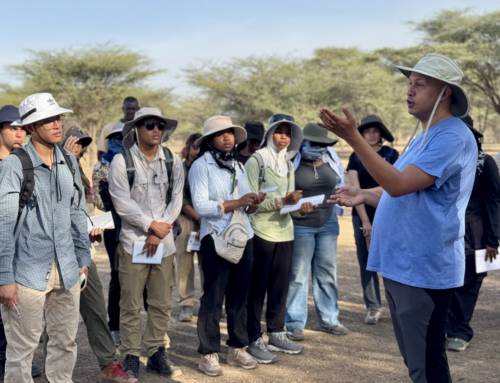

Students learning about vegetation at Mpala.

After our first lesson, Kimani brought students to the field in order to show them firsthand what his research entailed. They were able to see how the vegetation inside the compound drastically differs from outside of the compound. This contrast is due to the grazing of livestock and wildlife, limiting the growth of vegetation outside of the compound.

Kimani points out how vegetation in the compound is much more dense than outside of the compound.

Next, we drove north to investigate how differences in soil type can affect the size and diversity of vegetation. There are several different soil types in this area– we were looking at how the level of clay in the soil can effect the vegetation. Specifically, we compared a reddish soil with less clay and a darker soil with more clay. Due to its dark color, it is also known as the black cotton soil. The black cotton soil retains more water than the red soil, however, during the dry season it will dry up and crack, exposing the roots to the harsh environment. Thus, there is significantly less variety in the plants that grow here. In fact, when looking around, it is difficult to spot a species of tree that isn’t the Acacia drepanolobium.

Kimani explains that the soil is composed of varying amounts of clay and sand particles.

Mattia assists Kimani by adding water to the soil to check the amount of clay.

By adding water to the sandy soil, one can determine how much clay is present. The less clay, the less the sediment will stick together.

Kimani conducting similar experiment but with the black cotton soil. This soil has more clay and therefore, it sticks together much better.

Jon decides to help out by making his own clay mixture. Kimani in background showing how well the soil sticks together with his mud worm. 🙂

In our next lesson, Kimani discusses the symbiotic relationship between the acacia and ants that live in domatia on the tree in this region. When an animal tries to feed on the tree, the ants swarm to that location and attack the animal, protecting the tree.

Kimani discussing Acacia drepanolobium.

Ants using the bulbous thorns (domatia) as shelter

In addition to ants, students learned about termite mounds and how they affect the local environment. Termites greatly increase the organic matter in the soil around their mounds by breaking down plant matter and other such organics, enriching the soil. In turn, there is greater diversity of vegetation in this area. This is seen with the presence of several different species of grasses that abound in this locale but not in the area outside of the termite’s influence. Grazing animals tend to heavily graze these areas, prioritizing them because of the increased nutritional value.

Kimani shows the students that where termite mounds are found, there are several species of grass

In the afternoon, we again rode north during our field excursion. As you travel north inside Mpala, the precipitation level decreases while the amount of grazing livestock increases. As a result, there are very apparent differences in the vegetative patterns in the landscape.

Kimani discusses how this succulent plant produces a poisonous latex for self-defense.

Carla examining an acacia mellifera.

The students take a closer look at the flowers on this acacia.

Tobias closely examines this poisonous cactus.

Danielle is smart not to touch with her hands. This cactus is very poisonous!

To tie it all together, students performed similar field methods to those who study vegetation. One area was chosen for data collection for Kimani’s new project on grazing methods and preferences of giraffes found in Mpala. Students made transects in order to accurately map particular plants in a set area. For the students’ practical, they used a transect distance of twenty meters and measured any vegetation five meters from that line. During the practical, we saw giraffes grazing in the distance, a friendly reminder that what we were doing was for a great cause!

Esther and Danielle recording data

Millie, Jon, and Max discuss and measure the distance of this tree from the transect line.

Max measuring the crown height of this plant.

Kathryn recording data for her group.

This group works together to accurately begin a new round of measurements.

Emily measures crown height.

Mattia looks on as this group measures crown height and distance from transect.

Jon measures crown height while his group enjoys the brief relief of the shade.

Our askari (security guard) Wilfred, making sure the students are safe.

Jayde helps extract some cacti needles from Morgan’s finger. Field work can be treacherous!

Can you find the giraffes in the distance?

Stay tuned for more on their exciting field work and adventures!