The students are now well into the Vertebrate Paleontology course with Dr. Bill Sanders from the University of Michigan. Professor Sanders has been teaching the students how to interpret the skeleton and teeth of animals in order to understand how they lived. You can understand a lot about an animal based on its bones. The bones tell you how the limbs of the creature were oriented and how muscular it was. From that, Vertebrate Paleontologists like Dr. Sanders compare the bones of fossil animals to the body structure of living creatures and they can start to form a picture about how the animal may have moved, what it ate, if it could swim or fly, and even how closely things are related to each other in an evolutionary timescale.

Professor Bill Sanders giving a lecture on Early Hominins found in Africa. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

Matt, Kifle, Ulla, Ann and Meaghan learning comparative anatomy in the lab. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

To test their growing skeletal knowledge, the field school traveled out to some fossiliferous outcrops in North Turkana. The students wandered over the open terrain all morning hunting for fossils in an area where creatures from 1.5 million years ago are slowly emerging from the dirt. Our Resident Director Deming Yang, who has worked in Kenya studying Paleontology for years, explained the correct procedures for collecting fossils and then the students were set free to explore. It isn’t hard to find fossils in a rift valley like the Turkana Basin! Every few steps you can find a fragment of darkened fossilized bone from an ancient African animal. The students found and identified dozens of fossils and they were logged in as the official “Discoverer” in the TBI fossil directory.

The field school hiking into the field to hunt for fossils! (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

Meaghan, Ulla, Matt and our Resident Director Deming Yang searching for fossils. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

Dr. Sanders is an expert in Vertebrate Paleontology and developed a series of lab exercises for the students to compare the anatomy of different African animals. The students have spent a lot of time in the lab this course learning not only the names of the different bones in the skeleton, but also what each shape means in terms of that animal’s abilities and evolutionary history.

Professor Sanders explaining ecomorphological concepts to Gill and Rohan. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

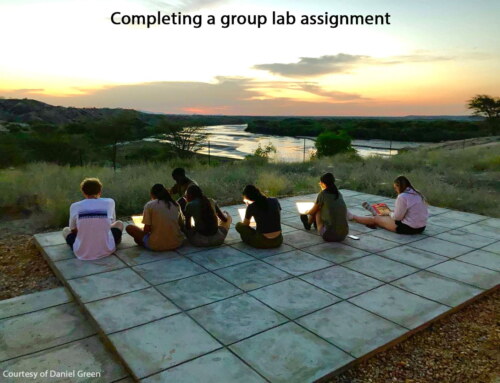

Their final project is a group exercise in “Ecomorphology.” This is the idea that if we study the shape of an animal’s bones we can learn about its habitat and lifestyle. Was the animal adapted to run fast? Did it have jaw muscles that could crush seeds, or crush whole bone? In our own human evolution, we’re particularly interested in discovering the point in time when our ancestors went from being quadrupedal (walking on four limbs) to bipedal (walking on two limbs). Therefore the students have been studying the human vertebral column, the long stacked column of bones that makes up our spine, as well as the vertebrae in other animals to look for differences in shape and ability. For their Ecomorphology project, each team received the skeleton of an unknown animal. Their challenge is to look at the bones and tell us what behavioral abilities they can infer from studying the features.

Georgina, Ulla and Meaghan working on their Ecomorphology project. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

Suid (Warthog) Skull. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

Lydia, Pauline and Matt working on their Ecomorphology project. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

One of the most exciting things for the students this week was our trip to the TBI Fossil Preparation Lab and Fossil Storage facilities. In the Fossil Preparation Lab the expert preparators working at TBI showed the students how to use an “air scribe.” These are tools used to carefully separate a fossil from the sediment that encases it. Each student got to try cleaning their own fossil and were told that they could come back to hone their skills in their free time. Many of the students are eager to go back and learn more about careful fossil preparation.

Georgina and T.A. Lucy watch Ann as she carefully prepares a fossil. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

Rohan watches as Gill carefully prepares a crocodile skull fragment. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

Georgina using the air scribe to clean her fossil specimen. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

Nick cleaning a fossil. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

In our tour of the TBI Fossil Storage facility the students explored a series of rooms filled with an incredible array of beautiful fossil specimens; rhino, crocodile, elephant, monkey and even ancestral humans. One of our favorite finds was when Professor Sanders showed the group the femur of an extinct species of elephant, Elephas recki, which lived in the early Pleistocene, stood over 4.5 meters tall at the shoulder, and is estimated to weigh approximately 15 tons! Many of the students took pictures with this specimen, and had to use their whole body as a scale.

Modern skulls (not fossilized) in the TBI Storage facilities. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

Professor Sanders showing the students elephant fossils discovered in the Turkana Basin. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

One of the many hallways in the fossil storage facility at TBI. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

Matt and Rohan examine rhino skulls in what we’ve dubbed, “The Hall of Wonders.” (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

Kifle, Regina, Tom and Lydia examine the fossilized skull of crocodile. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

Students explore the fossil storage labs. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

Kifle uses his whole body as a scale to demonstrate the massive size of this Elephas recki fossil femur. (Photo: T.A. Rosie Bryson)

We’re coming to the end of the Vertebrate Paleontology module and after their final exam in a few days we’ll have a relaxing weekend filled with trips to the lake, a soccer match and as always, more fossil hunting!

Stay tuned.