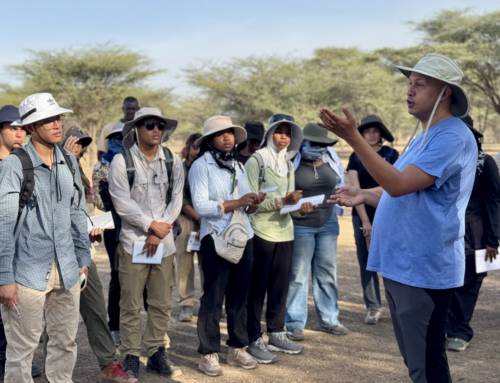

As we start our new course, Vertebrate Paleontology, taught by Prof. Ellen Miller of Wake Forest University, students are ready to put in practice all the amassed knowledge and skills from the last two courses (Ecology and Geology) in reconstructing paleoenvironments, and describing geological contexts in which fossils are found. The week started with an introductory lesson on evolution. Understanding evolution is important to paleontologists, as it enables them retrace how organisms came to be the way they are today. Dr. Miller discussed evolutionary theory before Darwin, citing Cuvier, de Buffon, Lamarck, Hutton, Lyell, and Malthus as key pioneers in the development of the theory. Darwin described natural selection as one of the primary factors that caused gradual change in species. He argued that new species formation depended on variation, competition for survival, and reproduction with traits that were heritable. Natural selection targets individuals as the units of change, selecting fit ones for survival.

Dr. Miller gives a lecture on evolution. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

To understand the appearance and disappearance of organisms on Earth, Dr. Miller assigned students an activity that involved unrolling the Earth’s history on tissue paper, in what is termed a “toilet paper timeline.” Students had to use 400 squares of tissue paper to sketch the 5 billion years of Earth’s formation, with each square representing 12.5 million years. They marked some of the important events in Earth’s history, including the period when life first began in the oceans (3.5 billion years ago), extinction of dinosaurs (65 million years ago), and recorded human history which began about 10,000 years ago. Students were able to visualize the age of the Earth, and onset of life forms through time.

Clara and Jared tape their toilet paper. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

Joe and Amber lay out their toilet paper on the floor. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

Emma and Michael unroll their paper. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

Zak and Becca used trunks to avoid going round the building. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

Students working on their timelines. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

Amber sketches the first photosynthetic event on the tissue. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

Becca and Zak work together to complete colouring their major events. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

Amber and Joe got innovative and created a volcano, and also drew extinct dinosaurs. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

The onset of photosynthesis 3.25 billion years ago. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

On Tuesday, Dr. Miller introduced the students to speciation and phylogenetics. Speciation involves the formation of new species from old forms, while phylogeny represents these relationships through time. Darwin envisioned speciation as a branching event, where new forms emerged from the ancestral one. Sorting out evolutionary relationships is challenging, as it involves meticulous identification and differentiation of ancestral and derived characteristics. Students had to create a phylogenetic tree of “critters,” imaginary organisms (caminalcules) invented by Joseph H. Camin. They were able to successfully reconstruct the phylogenetic trees as they learnt more about the hierarchical classifications, convergent, and vestigial structures.

Michael, Zak, and Joe discusses features of the organisms. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

Clara and Emma draw evolutionary lineages. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

Dr. Miller assessing the evolutionary tree. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

Amber, Jared, and Becca discuss how to arrange organisms. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

Emma and Clara discuss convergence in their phylogenetic tree. Photo credit: Medina Lubisia.

More to follow from the osteology labs, where students are spending much of their time.