A new study highlights the dramatic biodiversity loss of carnivores in the Turkana Basin’s Sibiloi National Park by examining both ecological sampling methods and observations of wildlife by local pastoralists.

Sibiloi National Park is located on the north-eastern shore of Lake Turkana and is well known for its paleontological record of human evolution. Historically, Sibiloi was known as an area rich in mammalian fauna, with large herds of herbivores and a diverse and abundant assemblage of carnivores. However, hydrological developments within Ethiopia’s Omo River, together with the disappearance of larger fauna, led UNESCO to add the park to its List of World Heritage in Danger in 2018. Despite its unique fauna and due to its isolated location, this continued process of biodiversity loss is not well understood.

Striped hyaena in Sibiloi National Park. Photo credits: Daniel Burgas.

Historically, carnivore conservation initiatives have been based primarily on scientific knowledge, from a wide range of ecological sampling methods, such as camera traps and track (spoor) surveys. However, the estimates of these commonly used ecological sampling methods can be quite uncertain, especially in remote areas such as Sibiloi. Therefore, Indigenous and Local Knowledge—knowledge that an indigenous (local) community held and handed down through generations of continuous interaction with their environment ̶ have received increasing recognition. Yet, there is a tendency to compare and validate Indigenous and Local Knowledge from the perspective of scientific knowledge, and when they differ, there is normally a rejection of valid and useful Indigenous and Local Knowledge and a disempowerment of local communities.

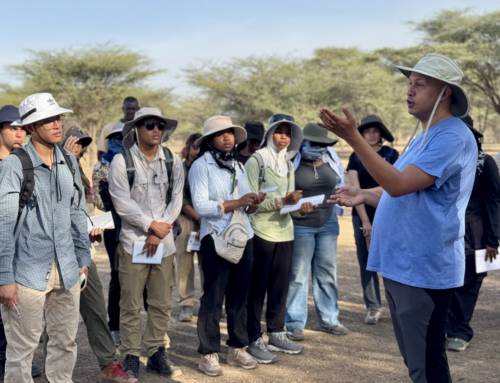

Collaborating with the Daasanach community on issues related to wildlife and ecology. Photo credit: André Braga Junqueira.

“The aim of the study was to clarify the unknown status of carnivore species in Sibiloi through a qualitative complementary approach looking at convergences and divergences between scientific and Indigenous and Local Knowledge”, explains Miquel Torrents-Ticó, the lead author of the study. In other words, the study complemented camera trapping and track surveys with interviews of local pastoralists to obtain a more complete picture of the unknown status and trends of carnivore species in Sibiloi.

The study also notes diverging insights between scientific and Indigenous and Local Knowledge. “Divergences are usually not taken into account because they can indicate stakeholders’ conflicts and can create challenges in effectively implementing conservation actions, but they can also improve our understanding of human-carnivore relationships,” Torrents-Ticó explains. “This study shows the importance of complementing scientific and Indigenous and Local Knowledge, and accepting both convergences and divergences to have a better understanding of the complex situation of carnivores and their conservation context.”

Overall, this complementary study underscores the urgent need for conservation actions in Sibiloi, before important carnivore species become locally extinct.