Pan of the Miocene Dead Elephant Valley in Buluk, Kenya

The last stop on the Turkana Miocene Project field tour was Buluk, Kenya, which has for many years been headed by Ellen Miller. Located east of Lake Turkana, Buluk is an early Miocene site that is rife with…. everything! It is a geologist’s and paleontologist’s paradise alike, featuring everything from bone beds to veritable cliffs of volcanic tephra (volcanic ash or tuff). Looking for an entire forest of fossil tree trunks and branches? Check. Fossil bones of every sort littering the surface? Check. Thick paleosol exposures, featuring both red AND green? Check. I have been working in the Turkana Basin for a few years, on both the west and east sides, and I must admit that Buluk has been my absolute favorite to work in, geologically speaking.

Valley of the Moon tuff

Buluk hosts several imaginatively named collection areas, including Dead Elephant, Smiling Lion, Valley of the Moon, the Big Sieve, Aaron’s Bone Bed, and more. Of particular interest, geologically speaking, are Valley of the Moon and Dead Elephant. Valley of the Moon is as the moniker evokes – a powdery wonderland of volcanic tuff, seemingly tens of meters tall. The units of tuff are as varied as they are beautiful: some are massive with no discernable structure, some are beautifully cross bedded, some are planar bedded with large pumice clasts, and some even appear to have graded bedding.

Greg Henkes acting as scale in front of cross bedded tuff exposures

Seemingly graded bedding in the tuff

Not only is this tuff geo-fabulous, but it is also useful for determining geologic age, if there is another tuff to which it can be correlated. Tuff can be used in the science of tephrochronology, or a process that now often uses Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) to chemically “fingerprint” the ash, obtain that chemical formula, and use it to compare to other ashes that have been tested. In this way, the ash can be traced back to a single volcano. Additionally, it is often possible to absolutely date tuff via radiometric 40Ar/39Ar (argon/argon) dating if it contains feldspar crystals. Needless to say, the Valley of the Moon may be a giant leap for Miocene mammal-kind.

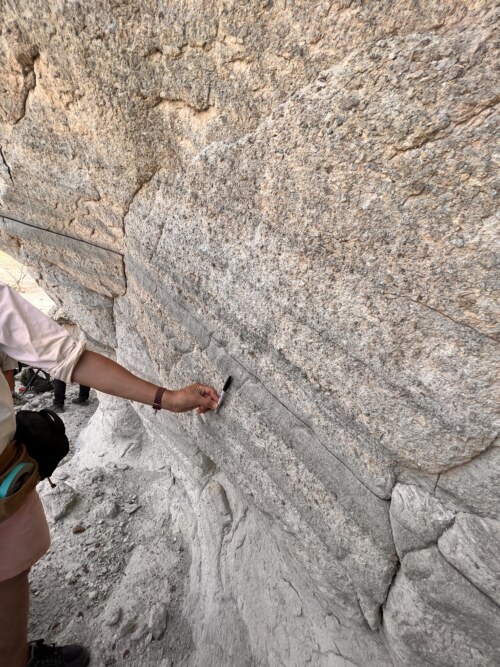

Although the Buluk Member type section is not located here, Dead Elephant is perhaps the most important area, geologically speaking. Just as Buluk has something for every Earth scientist, Dead Elephant has all the things for the geoscientist.

Possible fluvial (river) sequence. Note the purple units!

It appears that much of the member is exposed here in some fashion, albeit not as neatly laid out as in the type. Here, one can see fluvial (river) sequences, some volcanic deposition, which may ostensibly house the fossil trees, thinner exposures of the aforementioned tuff, an interloping tongue of basalt, a capping basalt, and even a messy debris flow, replete with basalt boulders, in which a small, mind-boggling lake deposit is nestled.

Freshly chopped wood pile? Nope! Miocene fossil wood littering the surface!

Understanding the processes that went on during Buluk times most certainly comes down to understanding Dead Elephant. All in all, our time working at Buluk was super-deluxe!

Interesting volcanoclastic debris flow at Dead Elephant.

Weird little (possible) lake exposure, nestled under the debris flow at Dead Elephant.

Authored by Melissa Boyd