The fourth week of the Harvard Summer Program in Kenya began with a day of rest and relaxation at Eliye Springs Resort on the western shores of Lake Turkana. Students swam, roasted coffee, and pet kittens, and a few of us bought handmade baskets after finding a group of people selling them nearby. For lunch, the restaurant served chicken, sautéed greens, French fries, and rice. After three weeks of classes and travel, this day at the resort was a great opportunity to decompress before fully diving into the upcoming geology module.

As evidenced by the submerged palm trees in the picture above, the water level of Lake Turkana has risen dramatically in recent years. The expanding area of the lake is partly due to high rainfall totals, which are likely to increase because of climate change. New land use practices, like deforestation and lakeside cultivation, exacerbate the problem by increasing the chances of flash flooding and landslides. Eliye Springs Resort provided satellite images showing the drastic changes in water levels over the past few years.

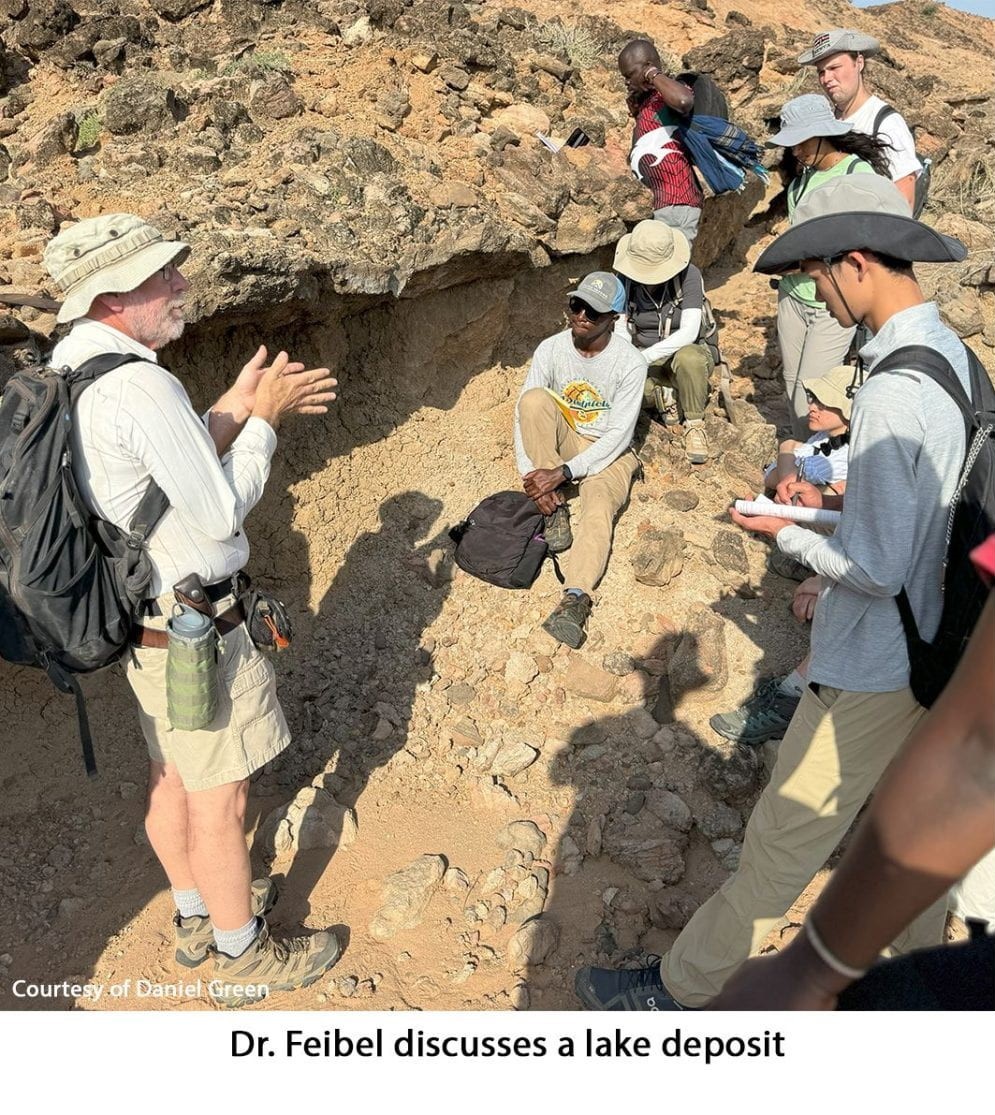

The next morning, we went out for a geology walk with Dr. Feibel, who brought us to see lake deposits just under 1 kilometer from camp. Some students were given GPS units, which were useful for entering points of interest and for general navigation. We learned that the modern Lake Turkana formed from about 250,000 to 300,000 years ago, and it became fully isolated from the Nile River 8,000 to 10,000 years ago.

After the hike, half of the group went to the lab to participate in a sieving and picking exercise with Dr. Ellen Miller, a paleontologist who does research at the nearby site of Napudet, which is about 13 million years old. After dry sieving and then wet sieving the sediment, it was distributed among the lab participants. Each student got two toothpicks and a magnifier to search the sediment for fossils, which were so small that they were difficult to identify with the naked eye. Nevertheless, Brooke found a piece of enamel, and Ben found a fossilized fish bone.

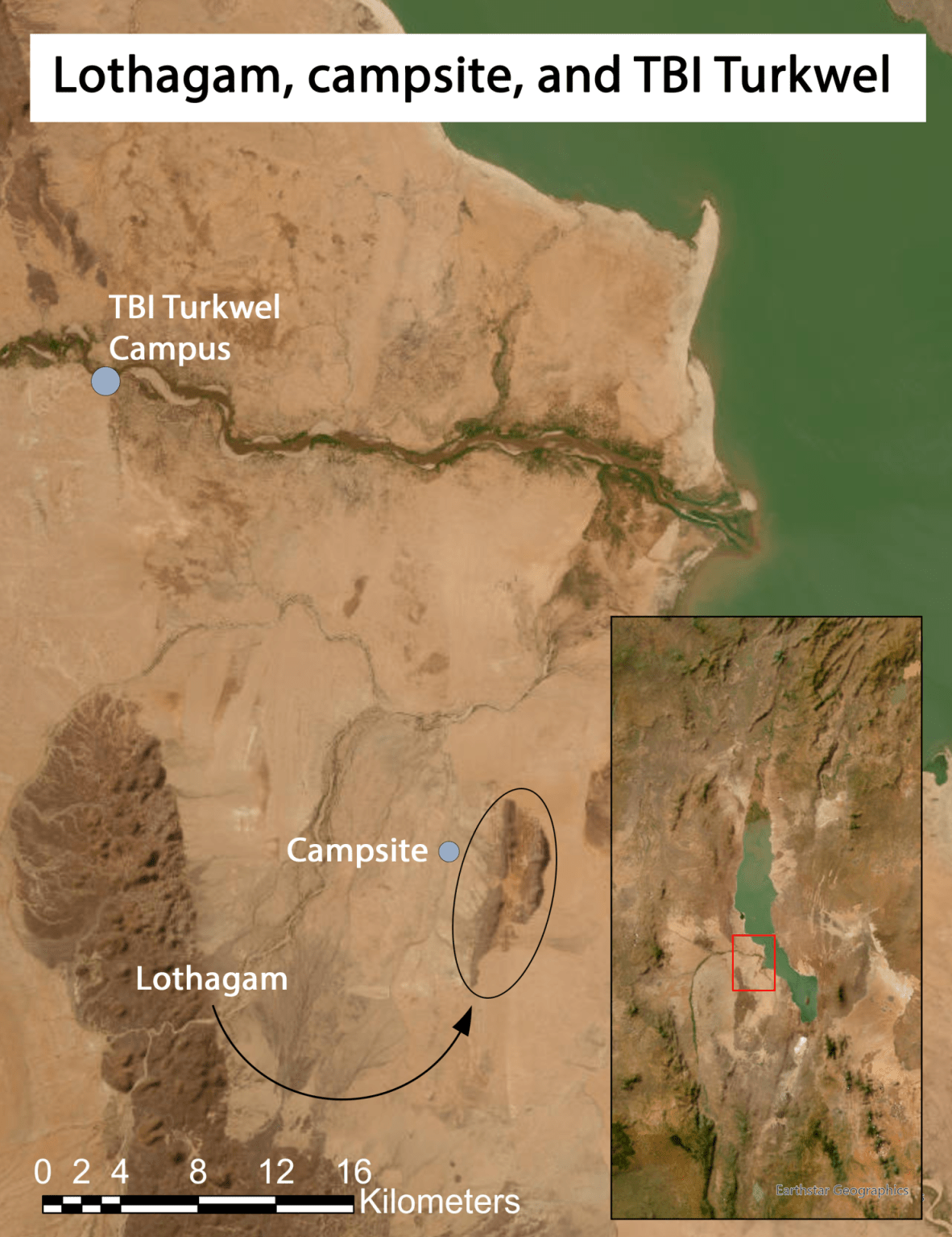

The afternoon featured a lecture by Dr. Feibel about the site of Lothagam: a geological formation about 30 kilometers southeast of TBI’s Turkwel Facility. We would be visiting Lothagam later in the week, so Dr. Feibel gave us an overview of what we could expect to see there. Lothagam has deposits that span millions of years, ranging from the Miocene to the Holocene, making it a rich research destination for geologists, paleontologists, and archaeologists alike. After hearing about the site from Dr. Feibel, students went down to TBI’s paleontology lab, where Emmanuel gave a tour and showed us some of the specimens that the lab contains.

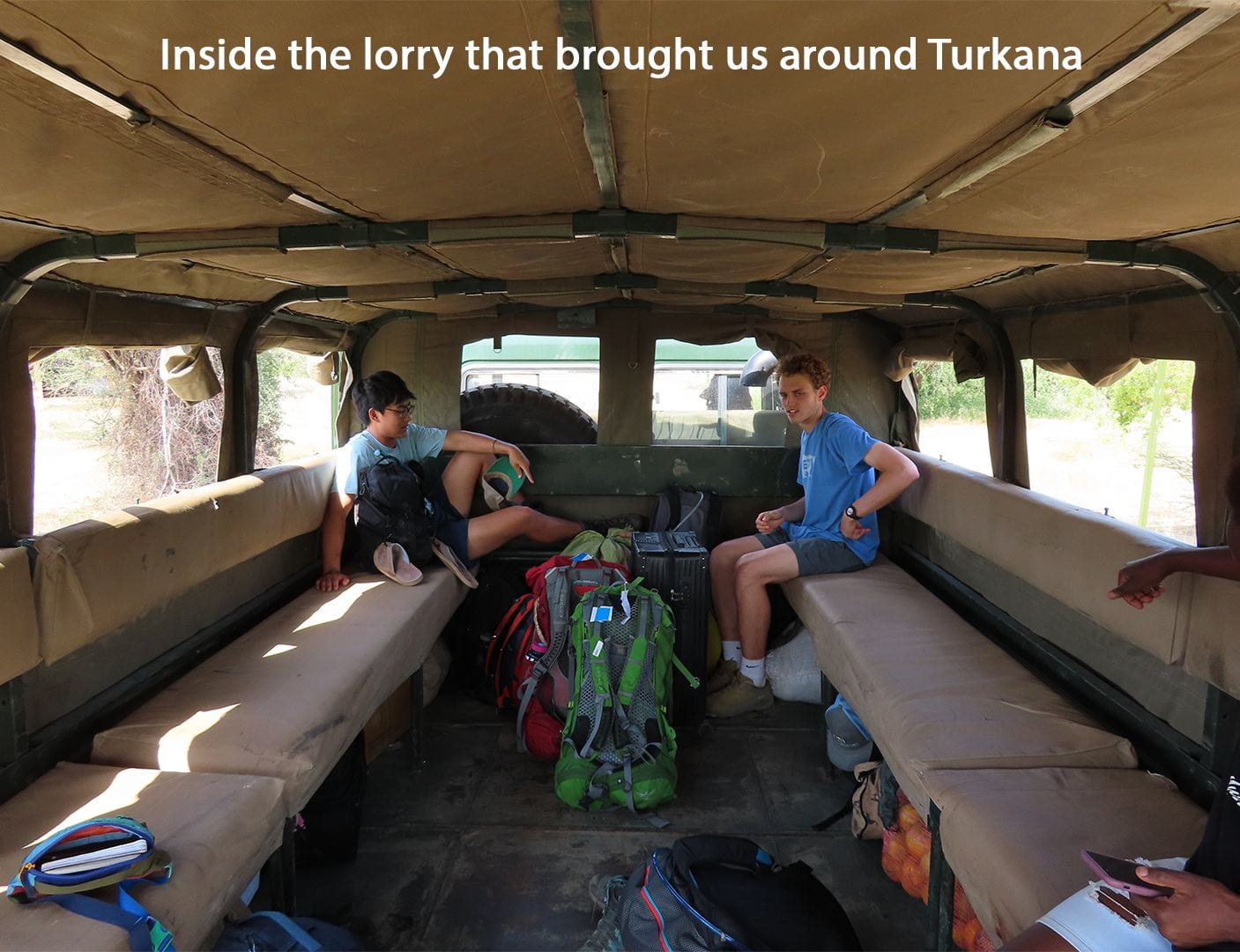

Tuesday, June 25th began with an excursion to the Turkwel River Delta to explore local fishing villages, and in the afternoon, visiting PhD student Elissa Day gave a lecture about Egyptology and taught us how to write our names in Egyptian hieroglyphs. That night, we enjoyed our last TBI dinner for three days, because the following afternoon, we would be leaving for Lothagam. We spent Wednesday morning learning more about the site from Dr. Feibel, who taught us some geological vocabulary that would be useful for our projects there and gave us some safety information. Later in the morning, the students who had not participated in Monday’s sieving and picking exercise had the opportunity to do so. We packed into the lorry that would take us to Lothagam at 3:00pm that afternoon.

The TBI staff had kindly prepared our tents for us upon our arrival at the campsite. We each had a tent to ourselves, and there were separate tent areas for women and men. Each tent had a cover to prevent dust from getting in, but it also kept the interior of the tent quite warm, so some of us decided to remove it in order to enjoy the cool nighttime breeze. At Lothagam we were a bit more exposed to the elements than we were at TBI, and we were specifically told to watch out for scorpions, which can deliver a dangerous sting. Another critter to be wary of was the solifuge: an arachnid that shares characteristics with both scorpions and spiders. They are large and fast-moving, but, despite what Turkana legend will lead you to believe, they are not particularly dangerous to humans.

We got settled in at camp and some of us went on a walk before the sun set and before dinner, which was served at 7:30pm. The view of the stars from Lothagam was incredible, and a group of astronomically-minded students used a laser pointer that evening to show the constellations.

The food at Lothagam was delicious and similar to what we ate at TBI. A standard breakfast included eggs (hard boiled or scrambled), small bananas, and toast or mandazis, and some of the dishes we were served at lunch and dinner were lentils, cooked vegetables, pasta with cheese, vegetable curry, goat, and baked potatoes. In addition to the kitchen, campsite amenities included jungle showers and latrines. Down the road from us lived a family group, who we often heard playing drums into the night.

Thursday, June 27th was our first full day at Lothagam. After breakfast, we got into the truck and drove roughly 20 minutes to the geological site, which we toured until about noon. Many of us immediately noticed the striking beds of red sediment, which date back to about 7 million years ago, during the late Miocene. Tectonic activities have shifted and tilted the landscape over millions of years, and today it is full of ravines and gullies, which make for exhilarating hiking. On the surface of the ground, fossils were everywhere. Some of the best finds of the morning included a 7.5-million-year-old rhino tooth found by Uzma, a 6-million-year-old gastropod found by Asher, and a 7-million-year-old fish pectoral found by Lily.

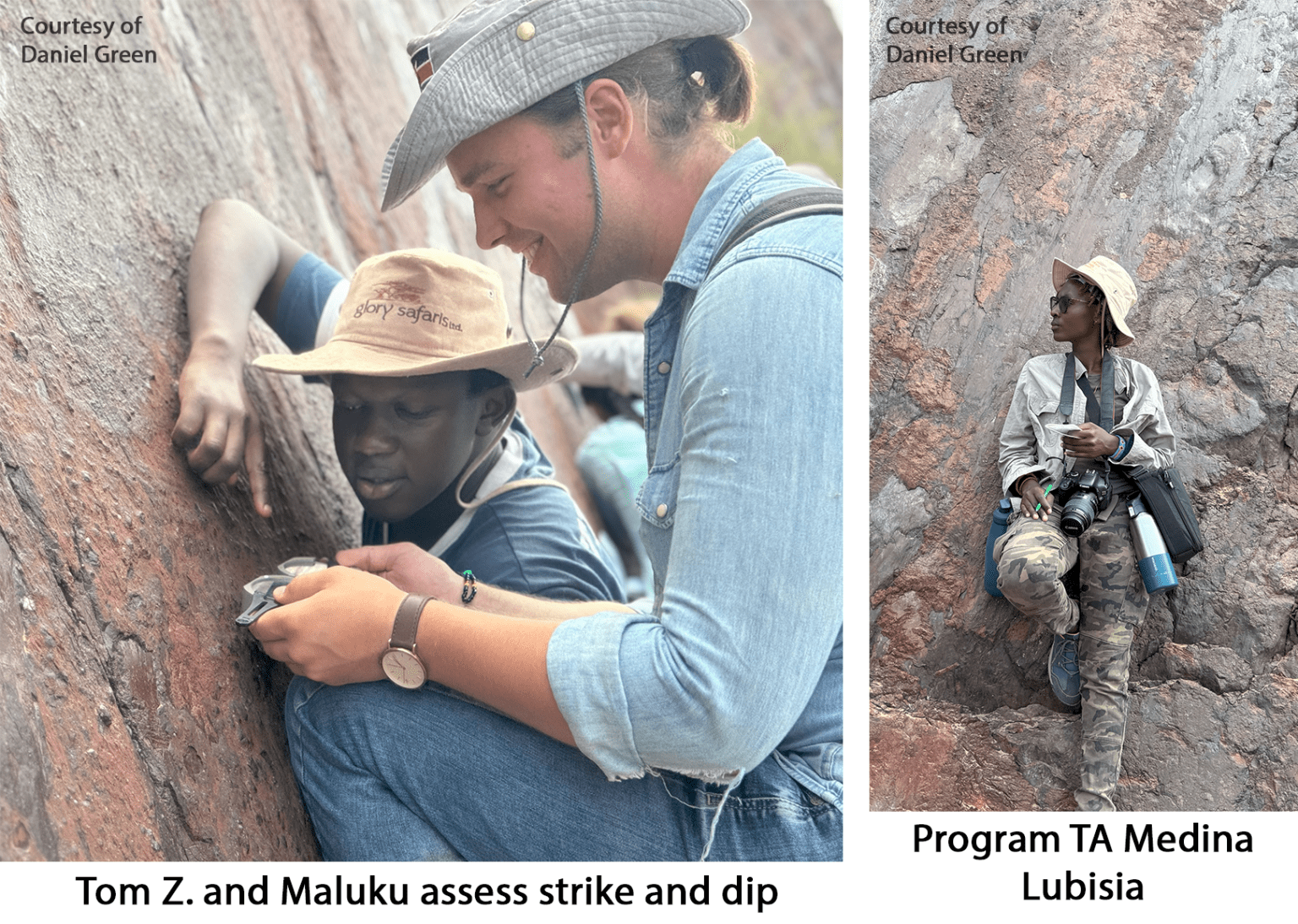

We had a break in the afternoon for lunch back at the campsite, and then we got back in the truck around 3:00pm to explore a new part of Lothagam. Dr. Feibel showed us a fault that is about 13 million years old, and he demonstrated how geologists measure strike and dip: two metrics that are used to assess the orientation and angle of any lifted bed or surface. Across from the fault were sand dunes, which made for great summertime sledding!

The next morning, students broke up into groups to begin their projects. Each group was assigned a geological feature, and their task was to make observations and ultimately interpretations about the feature’s geological history. All of the groups took measurements of different layers at different points in their feature and drew up a stratigraphic column. After a lunch break back at camp, we went out in the afternoon again, this time to see a local watering hole frequented by people, livestock, and a remarkable array of unique bird species, including the Namaqua dove: the smallest species of dove in the world. When we got back to camp, students took time to discuss their projects, which they would be presenting the next day.

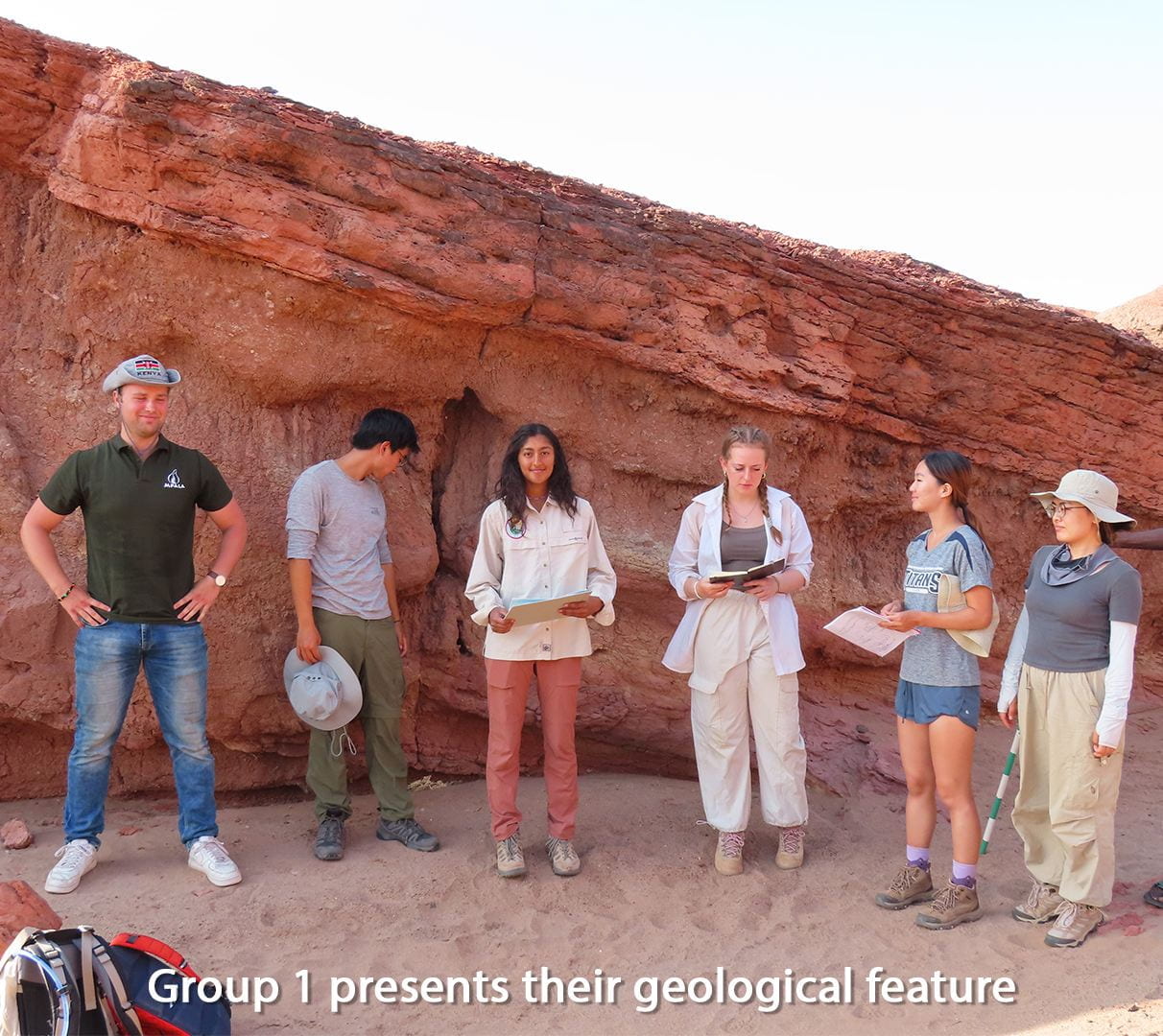

The presentations began with Group 1, which consisted of (from left to right) Tom Z., Sam C., Uzma, Brooke, Lily, and Wenli. They were looking at a volcanic deposit – likely the product of a series of river deposits – that was subdivided into layers including ones made of reworked volcanic ash and mudstone. The feature was from the late Miocene – a previous study had found one of its layers to be 7.5 million years old – and it represented about 20,000 years of time.

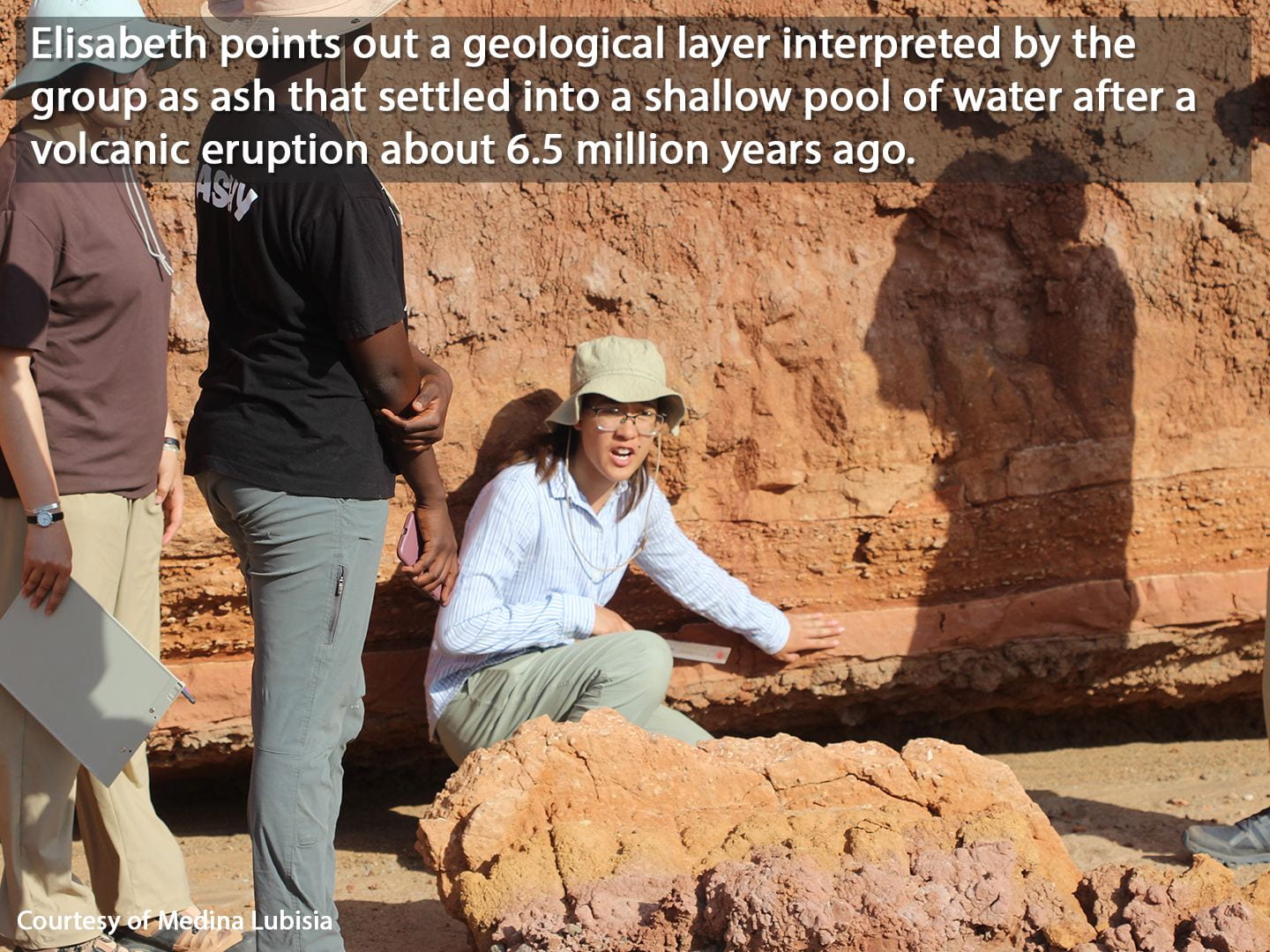

Maluku, Danny, Elisabeth, Ben, and Elissa made up the second group. They were studying a volcanic deposit that was also on the floodplain of a river, but parts of the deposits suggest that the ash was being deposited – possibly via airfall – in a shallow pond after a volcanic eruption. The group identified an ash layer and a pumice layer in their feature, and at some locations, they noticed a white layer of what may have been calcium carbonate at the interface between the ash and pumice. The volcanic deposit represents about 20,000 years of time and is about 6.5 million years old.

Group 3, consisting of Maggie, Tom O., Asher, Sam K., and Sylvie, was investigating a volcanic deposit that had two clearly delineated layers. The lower layer was nearly 2 meters of airfall ash, which was topped by a mudflow. The volume of airfall ash suggests that this deposit may have been closer to the volcanic eruption.

After the presentations, we hiked up to a part of Lothagam that is rich in holocene-era deposits, and is visually distinct from the rest of the site thanks to its white sediment beds, which upon closer examination we found to be made up of small shells. The view from this part of the site was impressive, and although dry land stretched on as far as the eye could see, the area was actually underwater about 8,000 years ago. As Lake Turkana retreated over subsequent millenia, pastoralist herders living around 3,000 BCE established a communal cemetery on what was at that point the lake’s shore. Today the burial ground is known as the Lothagam North Pillar site. It is surrounded by megaliths, and we found ancient pottery sherds scattered across the ground.

We returned to the campsite from Lothagam that afternoon. We had already packed up all of our belongings that morning, and while we were away, the TBI staff had broken down our tents. We had one final lunch at the campsite before loading our things and ourselves into the lorry that would take us back to TBI. Once we returned, we had the afternoon at the Turkwel campus to unpack, relax, and prepare for the upcoming module on paleontology and machine learning.