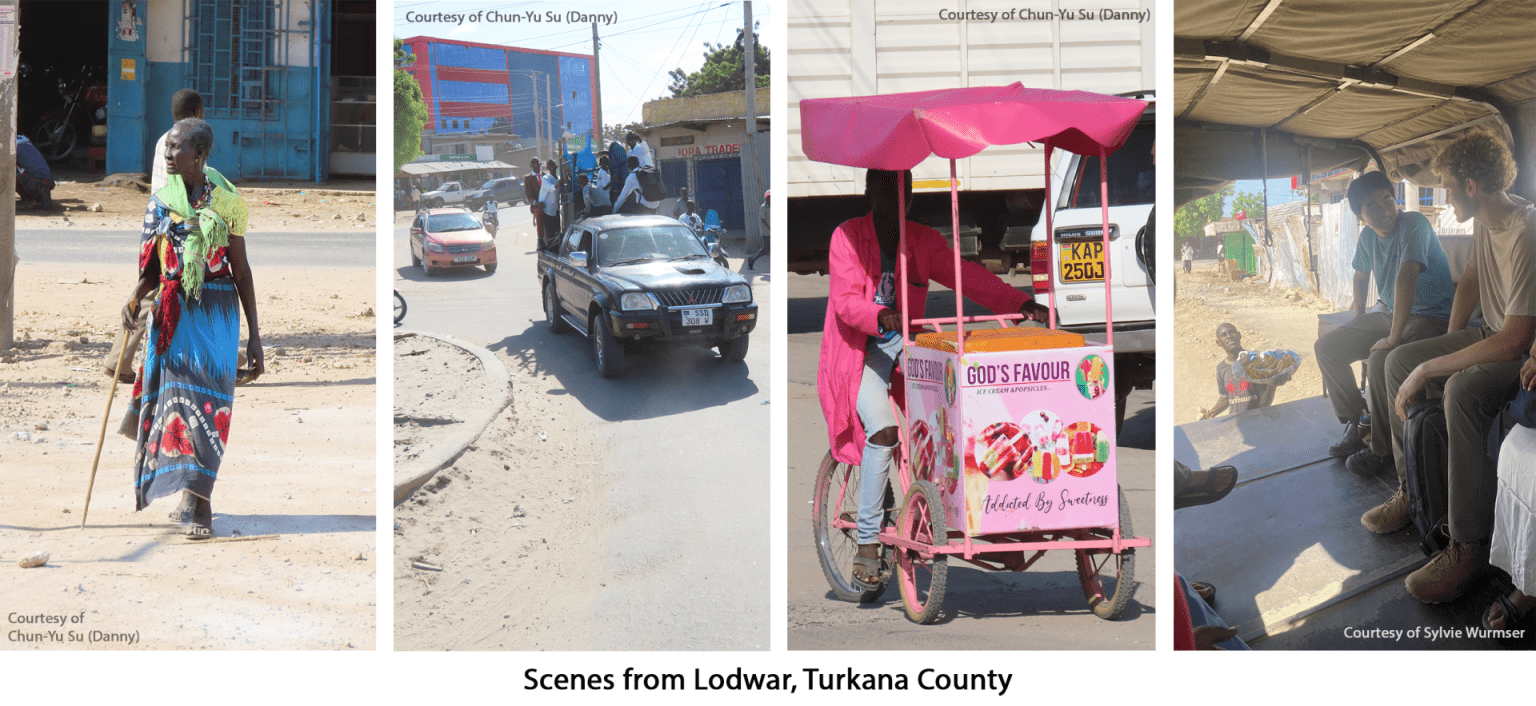

Week five of the Harvard Summer Program in Kenya began on Sunday, June 30th: our first full day back at TBI after the Lothagam visit. On Sundays, breakfast is served at 8:00am instead of 6:30am. Students had the morning to relax and/or work on readings, and some of us purchased merchandise that had been laid out by the TBI staff. Boniface Korobe arrived around noon to lead an optional lunchtime discussion about Turkana songs. After lunch, we had the afternoon off, but many of us decided to drive into Lodwar — the closest major town and the capital of Turkana County — as part of an optional shopping excursion. We were clear outsiders (or “mzungus” – a Swahili word for foreigners) in the crowded city, and we were grateful to have Medina and other TBI staff accompanying us. The urban lifestyle in Turkana existed in contrast to the ways of living in the rural villages that surround TBI, and we were generally approached with more curiosity, which was for the most part appreciated, but did feel overwhelming at times. Nevertheless, we had a great time exploring the streets of Lodwar. Many of us took the opportunity to restock on supplies at a local grocery store and to shop for souvenirs. The group that went to Lodwar returned around 6:00pm and had time to relax before dinner at 7:30pm. After dinner, a cake was presented to thank Dr. Feibel for his contributions to the program. We all had a slice.

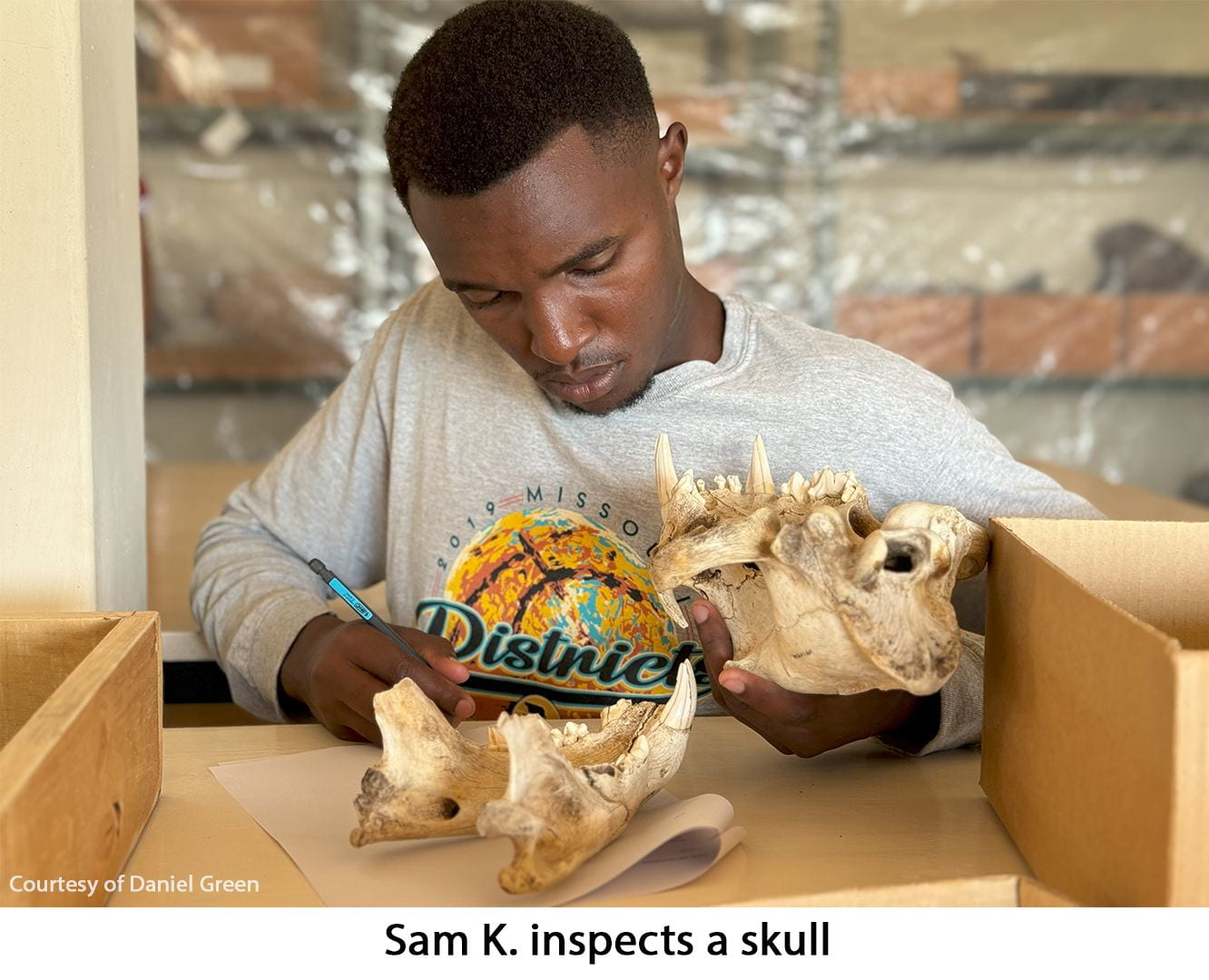

Monday, July 1st began at 8:00am with a lecture on chordate evolution and anatomy by Dr. Green. Chordates are a clade that emerged during the Cambrian explosion around 525 million years ago, and today they include a remarkable array of species ranging from lampreys and sea squirts to humans. Learning about this fundamental classification of life and some aspects of embryology set the stage for the lab activity later that morning, in which students observed the differences between the bones of various classes of vertebrates, including perissodactyls like horses and rhinos, artiodactyls like pigs and bovids, carnivores, and primates.

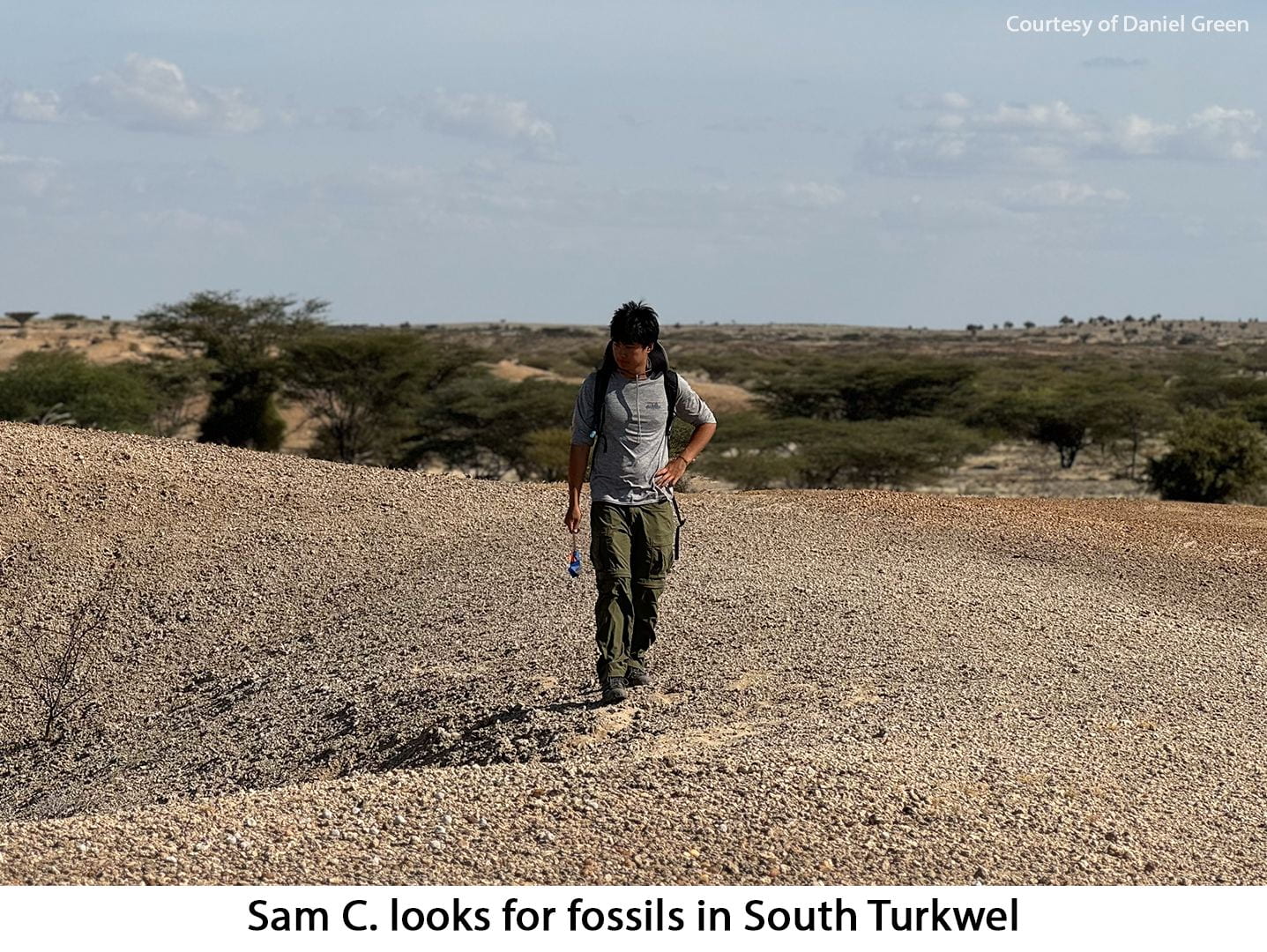

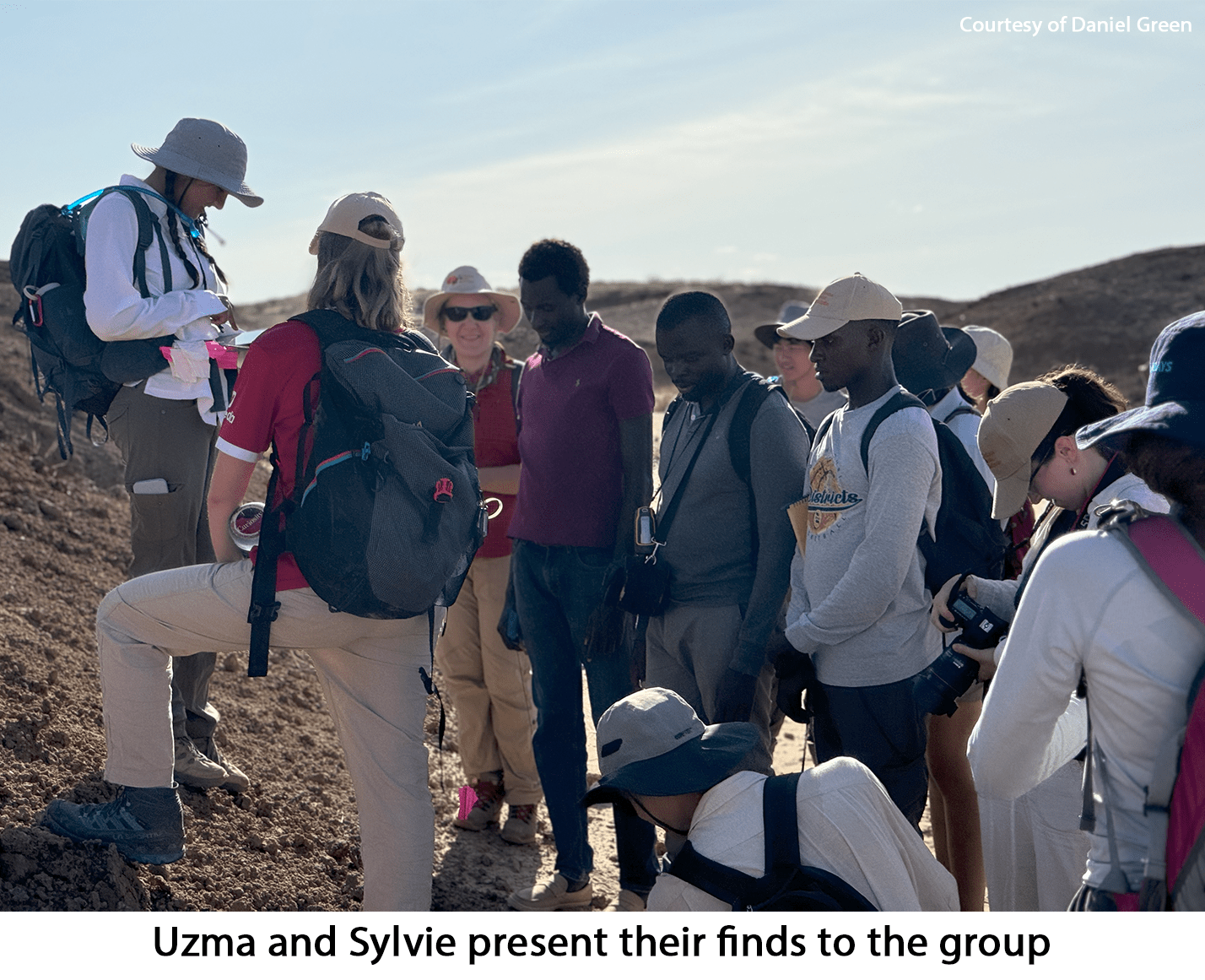

That afternoon, we left for South Turkwel: a nearby site that has yielded important hominid finds dating back to around 3.5 million years ago. We broke up into pairs and searched the area for fossils, the location of which we marked with small flags and on our GPS units. It was relatively easy to find bones on the ground, but ancient fossils were rarer. Nevertheless, multiple groups found remains dating back to animals that lived millions of years ago, and stone tools created by hominids were found as well.

About the activity, Dr. Green said:

“Students are going to spend the next week looking at databases that contain hundreds of thousands of fossils. It would be really great if while we’re here they found fossils and maybe even hominids. It would be a really great contribution to the work which has been conducted by all of the field explorers who are working here with the Turkana Basin Institute, but, importantly, whether they do or don’t find fossils, we want the students to understand that they databases they’ll be looking at, each one of those entries is the result of painstaking work by many, many people. This gives them a sense of how hard it is to find some of those fossils, and where the data that gives us information about our origins comes from.”

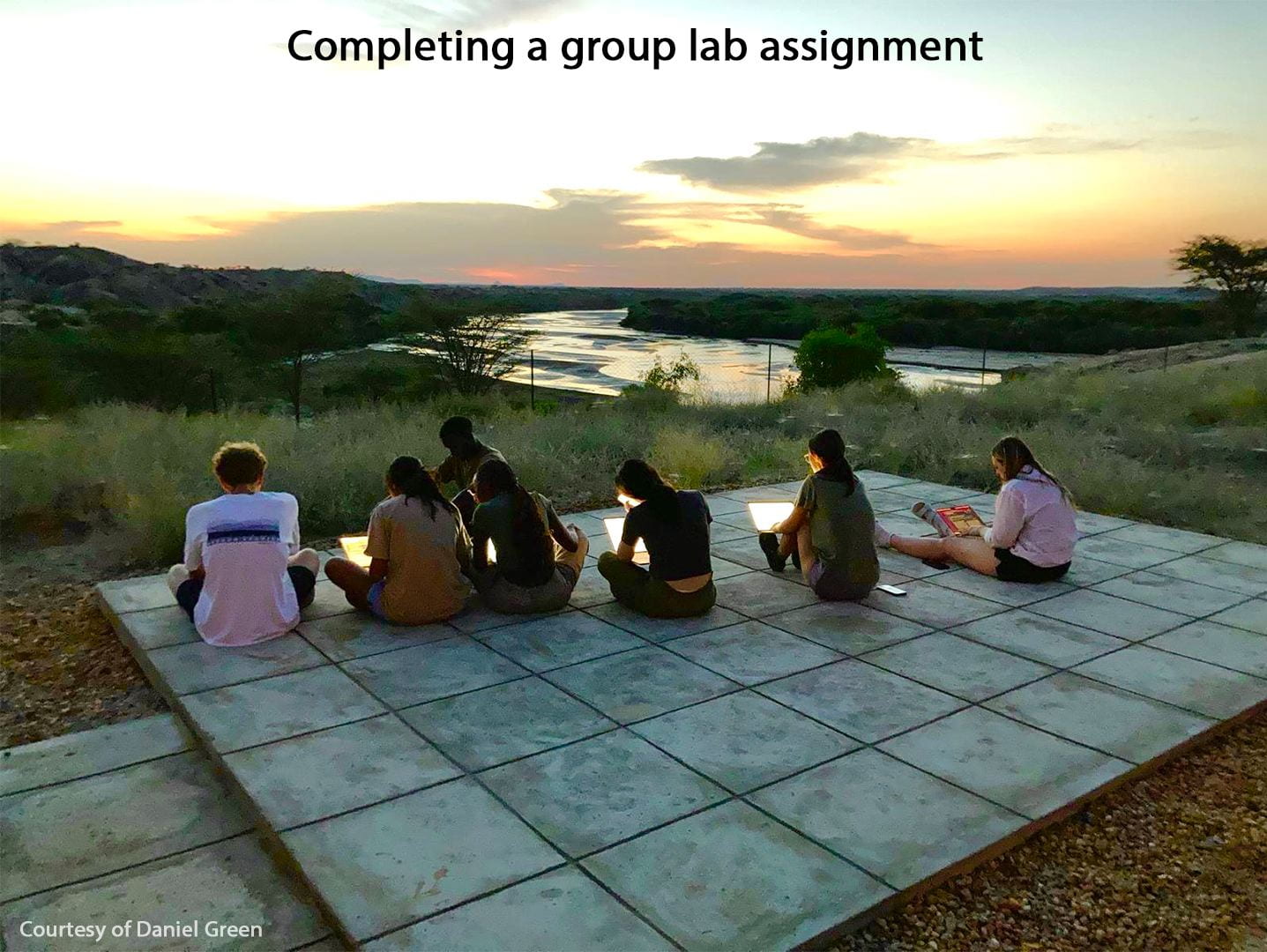

On Tuesday, we had our first lecture from Dr. Indrė Žliobaitė, a Finnish paleontologist who uses computation and machine learning to answer questions about prehistoric environmental conditions, both in Kenya and further afield. Her first lecture focused on paleontological databases, the difference between ecology and paleoecology, teeth, and some of the factors that impact whether a bone becomes fossilized. There was a quick break after the lecture, and then we reconvened to discuss the assigned papers. After lunch, students were broken up into groups to complete a coding assignment. The goal was essentially to use Python to query large paleontological databases. Using the New and Old World Database of Fossil Mammals, we compared fossil localities from Kenya, Tanzania, and Ethiopia that ranged in time from 34 million years ago to the present day. The lab ended around 6:15, and then we had dinner.

The next morning, Dr. Žliobaitė gave a lecture about computation, machine learning, and linear regression models, among a few other topics. Students had a break in the early afternoon for lunch, and at 3:00pm, we reconvened in the classroom and Dr. Green and Dr. Žliobaitė introduced the lab we would be working on for the rest of the day in the same groups as yesterday. Building off of yesterday’s assignment, the goal of today’s lab was to create models – a logistic regression and a decision tree, specifically – to predict the probability of certain taxonomic features, like fossil size and preservation. We were given a dataset that listed fossils and their preservation, completeness, and whether or not they were collected, and we were able to make some interesting inferences about collection practices. For example, almost no turtles or chordates were collected in our database, while many primates were collected. Most groups spent the remainder of the afternoon on this assignment until it was due at 9:00pm.

Thursday morning began with a lecture by Dr. Žliobaitė that built on what we had learned earlier in the week about machine learning. She told us specifically about her work using dental ecometrics to predict past environments, and she introduced us to the project we would be working on for the next two days. Our task was to predict environmental conditions using the dental traits of large herbivores which had been documented in the New and Old World (NOW) Fossil Mammal Database. We had the options of considering one fossil locality and how the dental characteristics of large mammals that inhabited it changed over time, comparing fossil localities over space, or using multiple models on a single fossil locality. Students spent the afternoon working on these projects in groups, and then at 5:00pm, we left for a dancing event with some of our neighbors at Nakechichok village. Dr. Kariuki had rejoined us at this point, and, with the help of Emmanuel as translator, he offered to help the local people determine the health of their livestock.

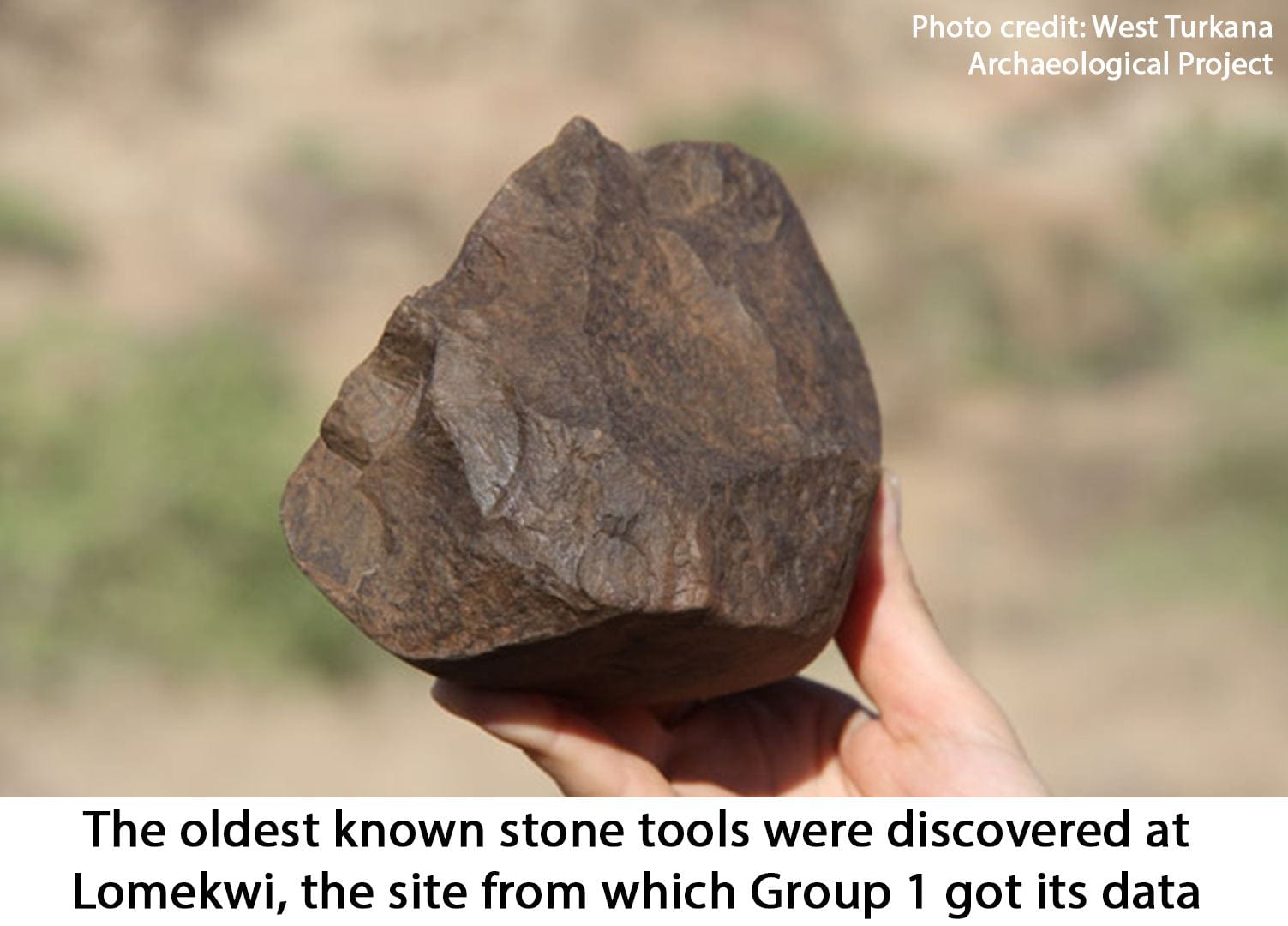

Friday, July 5th, was reserved for work on our group projects, the presentation of which began at 4:30pm. Ben, Muthoni, Sam K., and Uzma made up the first group, which focused their project on data from the site of Lomekwi, located on the west bank of Lake Turkana. They selected data that ranged in time from 3.94 to 2.1 million years ago and found a clear decrease in Mean Annual precipitation (MAP) and Net Primary Productivity (NPP) over time, indicating that the site was getting drier. Their results also indicate that the average temperature at the site slightly decreased over time and the vegetation cover shifted from woody savannah to savannah.

Group 2, consisting of Lily, Brooke, Tom O., Wenli, and Clara, focused on data from the site of Koobi Fora, which was located across the lake from us on the eastern side. Fossils from Koobi Fora range in age from about 4.9 million years to 3,000 years old, and the site has contributed data to paleontology, geology, and archaeology. The goal of Group 2 was to use dental ecometrics from fossils found at Koobi Fora to test if the site had decreased in aridity over the past few million years and created a suitable habitat for species diversity. The group used multiple models to predict changes in MAP and NPP at the site, and found results that were generally consistent with their hypothesis, despite some differences in the results produced by different models. They also ran average dental trait values through a decision tree to see how the vegetation cover was changing, and they considered the frequency of specific water-dependent species over time. An analysis of the specimen to species ratio at Koobi Fora suggested increased species diversity over time, which again was consistent with the idea of a climate that was decreased in aridity.

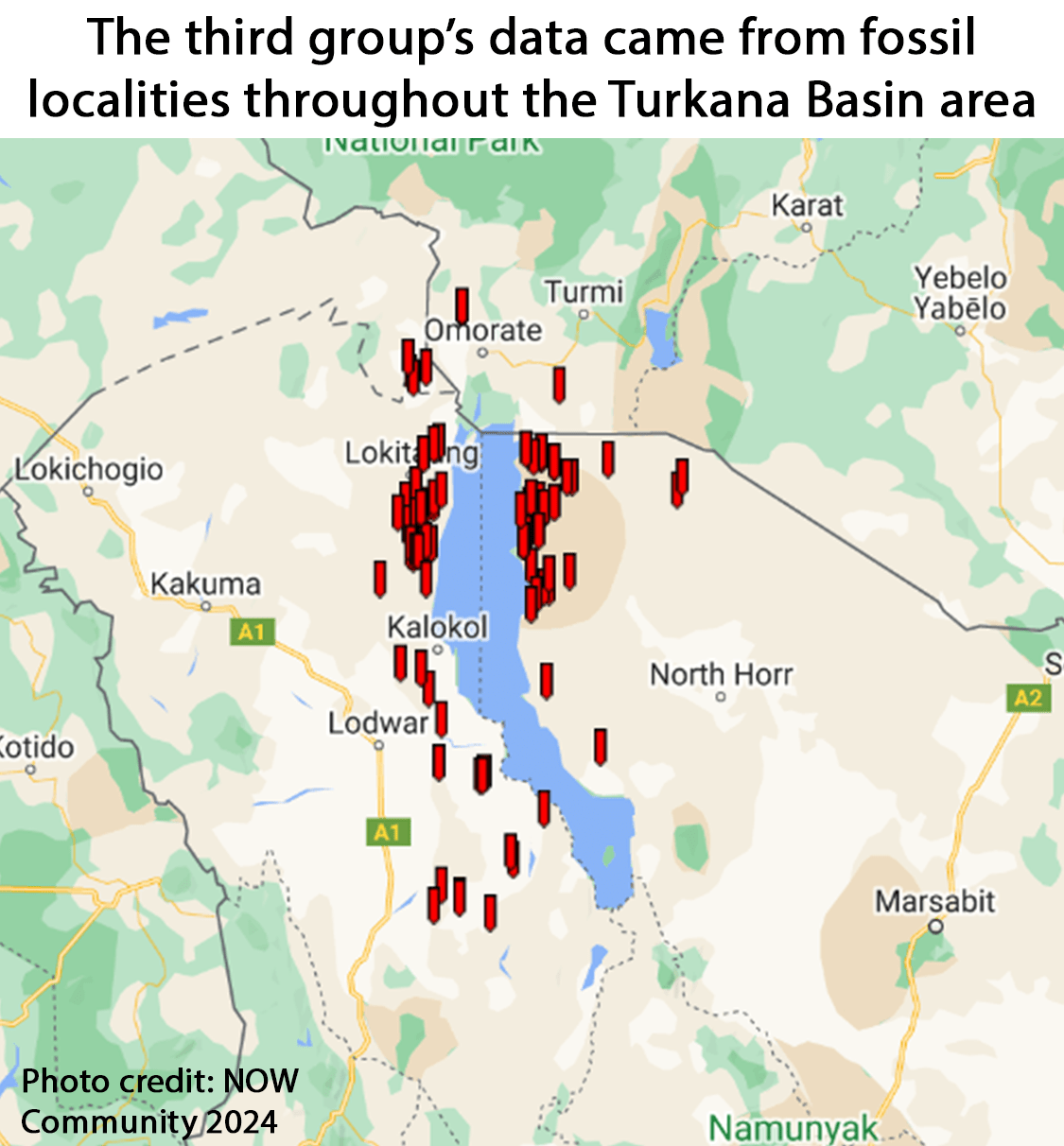

The third group, made up of Sylvie, Sam C., Maggie, and Tom Z., wanted to investigate the relationship between hippopotamidae prevalence and climate in the Turkana Basin. Hippopotamidae primarily consume the vegetation of C4 grasses and prefer slow running or stagnant bodies of water, so their presence indicates a climate that could support a constant water source and ubiquitous vegetation. The group calculated average dental characteristics across multiple fossil localities, and then generated calculations for MAP and NPP using multiple models. They ultimately found that the relationship between hippopotamidae presence or absence at a site and MAP to be inconclusive, but they did find a correlation between the presence of hippopotamidae and higher NPP. They concluded that this was a logical finding in part because modern-day hippo density is greater in areas that have more biomass.

The focus of Group 4’s project was Turkana boy: a roughly 1.5 million-year-old fossil that was discovered on the bank of a river near Lake Turkana and belonged to the hominin species known as Homo erectus. Asher, Danny, Maluku, and Elisabeth sought to use dental characteristics to better understand the climate in which Turkana boy lived, and more generally, the environment that supported this critical period of human evolution. Their analysis consisted of data from Nariokotome, Koobi Fora, and Illeret, which have all contained remains of Homo erectus. They downloaded dental information from the NOW database and calculated mean hypsodonty and loph count for large herbivores. Different models produced different results for MAP and NPP at each locality, but ultimately their findings suggested that when Turkana boy was alive, the area was experiencing cooler tropical temperatures – about 6 ℃ colder than it is now – and the east side of the lake was consistently wetter than the west side.

On Saturday, July 6th, the students went on an excursion to Central Island: a volcanic island in the middle of the lake, about 45 kilometers from the TBI campus. The group enjoyed a boat ride to and from the island, and scenic views of Lake Turkana. Emmanuel and Clara did not join the group, and instead used the day to visit Emmanuel’s grandparents in Turkana county and interview them about their beliefs about human origins.